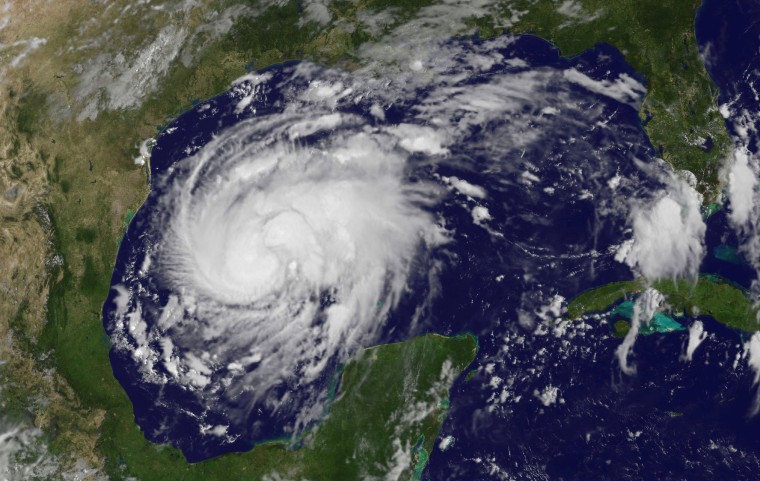

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season is officially underway, and if recent storms are any indication of what's to come, we may be in for a pummeling.

Last year, Hurricane Harvey slammed southern Texas and caused widespread flooding in Houston. And Hurricane Maria became the 10th most intense hurricane on record in the Atlantic basin when it devastated Puerto Rico and other islands in the Caribbean.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issues a hurricane season forecast each spring, and its forecast for the 2018 season specifies a 75-percent chance that this year’s storm activity will be at normal or above-normal levels. There's a 70-percent likelihood of 10 to 16 named storms — those with winds of 39 mph or higher. Of these, five to nine could become hurricanes, with one to four turning into major hurricanes (category 3 or above).

So exactly what can we expect this year? Have hurricanes become more intense and more frequent — and more deadly — as result of climate change? And are we getting better at predicting where and when hurricanes will strike? For answers to these and other questions, MACH's Denise Chow spoke with Kerry Emanuel, a professor of atmospheric science at MIT. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

MACH: How are hurricane season forecasts made?

Emanuel: Forecasters who are trying to make projections for the season look at long-range forecasts of climate patterns over the Atlantic Ocean. They especially look for the presence or absence of El Niño [periodic warming in sea surface temperatures]. Around May we can start to have a little bit of skill at forecasting whether an El Niño or La Niña [periods of below-average sea surface temperatures] might be in place by the late summer and early fall. We know that that affects hurricanes. El Niño, in particular, suppresses Atlantic hurricanes.

Forecasters also look at other sorts of seasonal predictions. For example, was the water temperature going to be warmer or colder than average, and is there expected to be more wind shear over the Atlantic or not?

I understand that since 1995 we've seen stronger Atlantic hurricanes. Why is that?

That's a good question, and that's somewhat debated in my field. There's one thing there's little question about: the waters of the tropical Atlantic are warmer now than they were in the 1980s. That is maybe a little bit because of the phenomenon of global warming, but a great part of it is likely due to the fact that there are fewer sulfate aerosols in the atmosphere now than there were in the 1980s.

One side effect of burning fossil fuels and burning land areas to clear them is that it puts particles in the atmosphere that have the effect of reflecting sunlight and making the planet's surface cooler. We had a lot of those around the '80s, and they started to decline in the late 1980s because of the Clean Air Act and variations of that in Europe and elsewhere. We cleaned up our act, which was a good thing, because those aerosols are very bad for our health — but a sad side effect of that is that without that cooling, the oceans started to warm up. That brought back the hurricanes.

What do we know about the effect of global warming on hurricanes?

I'm actually participating in a team put together by an organization called the World Meteorological Organization. It's a branch of the United Nations. We’re doing an assessment of where this whole question stands. There are several areas where there's a strong scientific consensus. One is that a given hurricane is going to produce a lot more rain as the climate warms, and we're beginning to see signs of that happening. That's for a very simple reason — that a warmer atmosphere has more water vapor in it. There's really no controversy about that. We expect to see more [Hurricane] Harvey-type events as we go forward.

Another indisputable thing is that the sea level is going up, and it's almost certainly going to continue to go up. The largest killer in hurricanes is something called the storm surge, which was what flooded New Orleans during [Hurricane] Katrina and New York during [Superstorm] Sandy. Even if the storms themselves don’t change, the surges are riding on an elevated sea level, and that makes them more dangerous.

There's also a reasonably strong consensus that we're going to see more intense hurricanes. That's because the theory that ties the sort of maximum speed limit that you can have on hurricanes is very clear. As you warm up the system, the speed limit goes up. We're going to see more intense hurricanes, and we are seeing signs of that in the data.

Within science, it's very controversial about whether the number of storms overall is going to go up or go down. We don't see any signs one way or the other yet. And we don't expect to — the data aren't good enough to tell us that.

Even if hurricanes aren't necessarily becoming more frequent, are they doing more damage now than in the past?

It's really hard to tell. There's another big factor in tropical cyclone damage in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world, and it's simply the fact that people are moving in droves to the coastline and building more and more stuff. That's producing a huge increase in damage from hurricanes. But if there's a climate change signal in there, it'd be really hard to tease it out. It’s mostly because more and more people are living in dangerous places. It's not much more complicated than that.

What keeps you up at night?

A lot of things. One is that we know from studying paleoclimate, or climates of the distant prehistoric past, that the climate system can change suddenly in ways that our models don't predict and that we don't understand. When we talk about global warming, the possibility that the system could suddenly jump to a different state does keep me and many of my colleagues awake at night. We have no way of knowing whether that will happen or predicting when or whether it will happen, but we know it happened in the past, and we know we don't understand it. That keeps me awake.

What do you mean by the system jumping to a different state?

We know that in the middle of these ice ages — like the last one we had — that suddenly, it would warm up for maybe 1,000 years and then go right back down to its state before. You had these sort of really sudden thaws in the ice age that didn't last long, on a geological timescale. Things went back to cold in maybe just a few hundred years. We don't understand those.

There are other things that happened in the past. During a period when it was extremely warm on the planet, more than 50 million years ago, when there was no ice anywhere on the planet except maybe on the peaks of very high mountains, there was a spike in temperature. It rocketed up very quickly, and then rocketed back down again. It was called the Eocene-Paleocene Thermal Maximum. We don't know why that happened, and so when we look at the record, there's certain things we do understand about it. But these other things that go on, like these big spikes, we don't understand, and it compromises our ability to predict what will happen in the future.

What else worries you?

The other scenario that keeps me awake at night, and a lot of hurricane forecasters, is something that happened in the 1950s. Let’s say you have a weak tropical depression in the Western Gulf of Mexico. You go to bed in the evening and it's intensifying but it looks like it might make landfall in two days, as maybe a weak hurricane, so you don't worry much about it. You wake up the next morning, and it's a category 3 storm intensifying rapidly, about to hit a populated place later that day. That happened. It was called Hurricane Audrey.

Most people don't remember it now because it was in the '50s, but it killed 600 people. The forecasters just couldn't get the warning out in time. You don't have time to evacuate people. Sudden intensification of hurricanes before a landfall is a scary scenario, and I wrote a paper last year that global warming actually makes that somewhat more likely than it has been in the past.