TASIILAQ, Greenland — When a severe thunderstorm rattled the town of Tasiilaq in East Greenland in April, it was all the 2,000 residents could talk about.

“Facebook was full of people saying, ‘I was doing this and then I heard the thunder,’ and when I went to my job, everyone was talking about it,” said Anna Kûitse Kúko, 63, who has lived in the coastal town for most of her life. “It’s just so rare. We maybe hear some thunder one time in 30 years. It was scary.”

For Kúko — who was born outdoors, delivered by her grandmother “in nature, just on the other side of the mountains” on the edge of town — the ominous roars, cracks and rumbles were just another way that she and her neighbors have seen their environment change over the last 15 years.

“When I grew up, the hunters and my father used to tell me: look at the clouds and look at the water because these will tell exactly how the weather will change,” said Kúko, who is among the 89 percent of Greenland’s population that identifies as indigenous Inuit. “That is almost impossible now. It’s unpredictable. And we know it is because of climate change.”

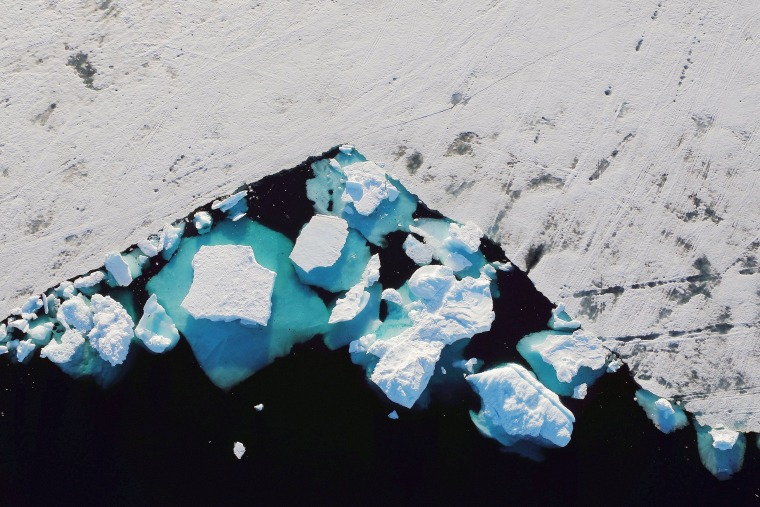

For many scientists, Greenland is considered “ground zero” for climate change, a place where global warming’s impact is most apparent — and where the effects of rising temperatures, warming oceans and melting ice could have the most dire consequences. But for the 55,000 people who make their home on this massive, ice-covered island, an autonomous Danish territory, the realities of climate change are complex, bringing both unexpected benefits and acute challenges.

Across the island, the unprecedented melting of Greenland’s glaciers is opening up new waterways for fishing and tourism. In Ilulissat, in West Greenland, these industries have thrived in recent years, bringing considerable wealth to the town, which sits nestled against a fjord so renowned for its towering chunks of floating ice that it is nicknamed an “iceberg factory.”

But elsewhere, particularly in East Greenland, the shorter winters and longer, warmer summers have endangered hunting, dogsledding and other traditional ways of life for Greenland’s roughly 50,000 Inuits.

“We're seeing unprecedented melting of the ice sheet right now, and Greenland's ice sheet is at the center of everything,” said Thomas Juul-Pedersen, a scientist and education coordinator at the Greenland Climate Research Centre in Nuuk, the country’s capital. “That can potentially have a big impact on Greenland and a big impact on the livelihood of the people here.”

On the heels of one of Greenland’s warmest summers, nearly everyone who lives on the 836,000-square-mile island is being forced to think about how to adapt to the potentially drastic changes that climate change could bring.

‘I cannot leave this place’

It’s thought that the first humans to arrive in Greenland reached its shores about 5,000 years ago, after a narrow strait in northern Greenland froze over, allowing nomadic tribes to trek across the frigid Arctic landscape from Canada. Several major waves of migration followed, and Greenland’s 50,000 Inuits are descended from these early settlers.

Before modern conveniences like roads and stores were established in remote towns up and down Greenland’s east coast, the Inuits who settled in these isolated corners survived the harsh environment by subsisting on seals and polar bears in the winter and reindeer and muskox in the summer. Prized catches — a coveted whale or bear — were shared with neighbors and friends, sometimes providing enough food for the entire community.

In Greenlandic Inuit tradition, men were the designated hunters, with fathers raising their sons to carry on the traditional ways of stalking prey in kayaks and dogsleds. It’s a culture that prides itself on adapting to the whims of nature, and many have carried on their ancestors’ tradition of living off what’s available on land and in the sea.

Fewer people need to hunt for sustenance now that meat and fish can be purchased at grocery stores, and most hunters in Tasiilaq today treat it more as a hobby than a necessity. Still, hunting retains a deep cultural significance, even as global warming has made the seasons more unpredictable and ice conditions increasingly volatile.

“When I was a boy, before Christmas, we used to go ice fishing,” said Axel Hansen, 43, who was born in Tasiilaq. “Now it is impossible. We have to wait almost two months after Christmas. The snow is not so good anymore — it’s soft and wet. In the old days it was hard and easier to go hunting and dog sledding. Now it is not so good.”

Such drastic changes to ice conditions can have deadly consequences. Kúko, who works as a teacher in Tasiilaq, said four people have drowned from falling through thin ice in the past 15 years — an unusually high number for a town of experienced hunters who grew up using dog sleds, not snowmobiles, and harpoons, not shotguns, to nab their prey.

“It is much more dangerous to go on the ice now,” she said. “It’s unpredictable and more thin, so you can easily go through the ice and drown. Hunters used to know exactly how the ice would be.”

Life in Tasiilaq, as it is for much of Greenland’s more remote eastern flank, can be difficult. For most of the town’s existence, the thick sea ice that forms during the winter months in the bay prevents ships from being able to reach the harbor. This means Tasiilaq, reachable only by helicopter or boat, can sometimes go up to six months with limited access to fresh produce and other supplies.

Hansen, who has warm eyes and a shy demeanor, says he grew up poor there, raised by a single mother. He works at The Red House, a guesthouse in Tasiilaq that, somewhat improbably for a tiny town with just one restaurant, is becoming a tourist destination.

Sitting at The Red House’s long wooden dining table with dozens of pairs of kamiks — traditional knee-high boots made from seal skin that are part of the ceremonial costume worn by Inuit women — decoratively displayed on the walls, Hansen said he dreams of hunting and fishing full-time. It’s unlikely, though, that he could make enough to cover his bills. His two sisters have moved to Denmark and have urged him to do the same, but he says he’ll never leave.

“My heart belongs here, in nature,” he said. “I cannot leave this place.”

‘There was no more snow left’

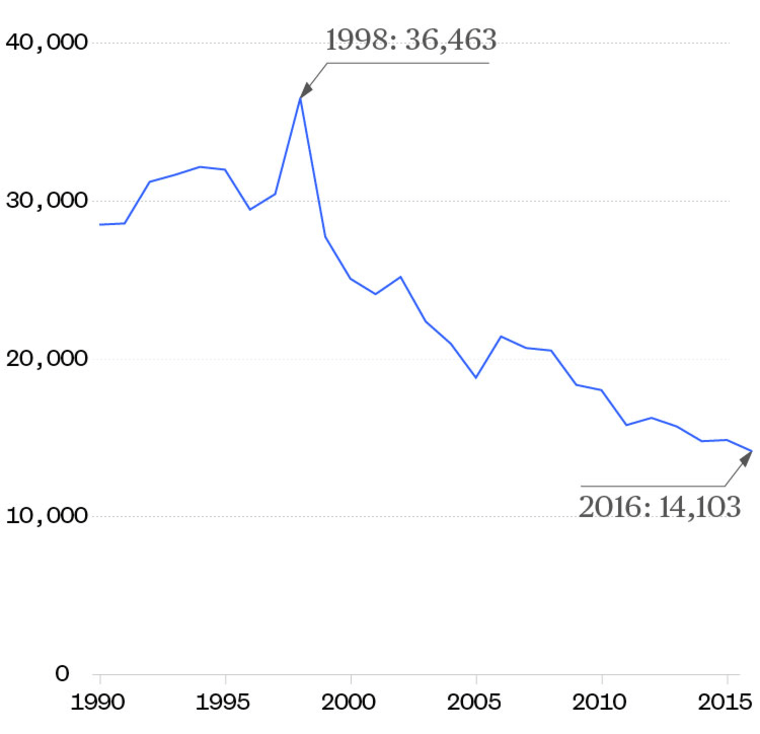

Global warming has also imperiled sled dogs, which have long played a key role in Inuit culture, not only as companions, but as a primary mode of transportation. With increasingly unpredictable winter seasons, fewer locals are keeping dogs, and their numbers in many towns across Greenland are falling precipitously.

Though they resemble malamutes and huskies, Greenlandic dogs are their own ancient breed. It’s thought that these energetic pups were brought to the island about 1,500 years ago, when people from coastal Alaskan settlements migrated eastward across the Canadian High Arctic and eventually into Greenland.

Historically, towns like Tasiilaq had more dogs than humans, but their numbers have dwindled over the past decade. In Ilulissat, in West Greenland, about 5,000 dogs were kept by locals more than 25 years ago, a number that has dropped to about 1,800 today, according to municipal government officials.

Number of sled dogs in Greenland

“The dog is the most threatened animal in Greenland,” said Rasmus Poulsen, 27, who was born in Denmark but moved to Greenland six years ago and now lives and works in Tasiilaq. Two years ago, Poulsen started a company, Tasiilaq Tours, which offers dogsled tours during the winter months. Taking tourists on sledding adventures can be lucrative, but it’s also dependent on the weather.

This past winter looked to be a profitable one. Poulsen had a handful of tours scheduled in March and was fully booked for April. But then, the weather turned.

“I had a film crew coming here but we only managed to do half of the production dates because it started raining,” he said. “Then, I had two other dogsled tours that were not very successful. We managed to make it, but it was very slippery. We couldn’t get very far, and we were riding on pure ice because there was no more snow left. We could only go out on the fjord, and the second we hit the other side, there were 10 meters of snow and then it was just rocks and grass.”

More of these warm winters, particularly if they happen consecutively, could doom the tradition.

“If that continues, we could say that all dog sledding will be dead,” said Lars Anker-Moeller, who founded the Tasiilaq-based adventure tourism company Arctic Dream in 2007. “It just won’t be possible to do these winter activities.”

Many dog owners in Greenland use tourism as a supplemental income. When he isn’t giving tours, Poulsen does freelance work at the Ammassalik Museum, a red-painted structure near Tasiilaq’s harbor that displays East Greenlandic cultural artifacts in the town’s former church.

But the dogs have become a drain on Poulsen’s income, rather than a boon. The shorter winters have made it difficult to offset the $3,200 it costs to feed his 15 adult dogs annually — not to mention the time and effort required to train them to follow commands and pull sleds.

Poulsen is passionate about dog sledding, and its place in Greenlandic culture, but he’s also pragmatic.

“It would be very sad not to be able to do it, but as an owner of a small business, it’s a big expense,” Poulsen said. “If we have a lot of winters like the one we had, where the season ended really before it started, I’m not going to have dogs for very long.”

‘See Greenland before the ice melts’

Just what Greenland’s future will look like is something that scientists are still trying to figure out. In some ways, this island is a perfect laboratory for studying the effects of climate change. The Arctic environment is sensitive to even tiny changes in global surface temperatures, and what happens to the ice locked up here, and elsewhere at the planet’s poles, has enormous implications for the rest of the world.

This summer — which included the hottest July in recorded history thanks, in part, to historic heat waves in Europe — Greenland is expected to lose an estimated 440 billion tons of ice. That's a tiny fraction of Greenland's sprawling 656,000-square-mile ice sheet, but it's enough to fill approximately 176 million Olympic-sized swimming pools. In August, Danish officials reported that 11 billion tons of surface ice melted from Greenland’s ice sheet in just 24 hours.

There are some natural yearly variations, but if this rapid pace of melting continues, some climate models estimate that the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free in the summers by 2050. If Greenland’s ice sheet were to completely melt, global sea levels will likely rise more than 20 feet, reshaping the world’s coastlines and submerging low-lying cities such as Shanghai, Amsterdam and New York.

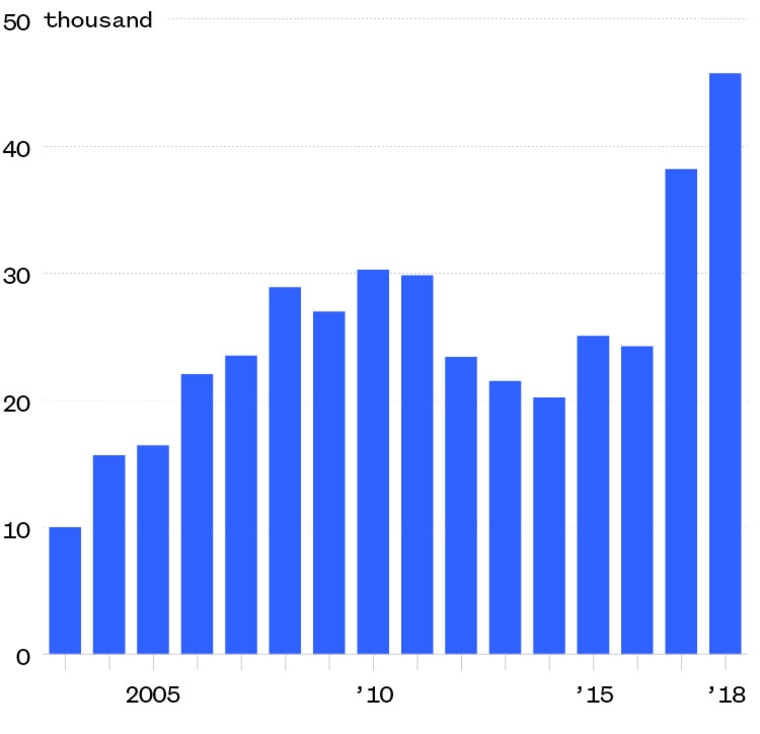

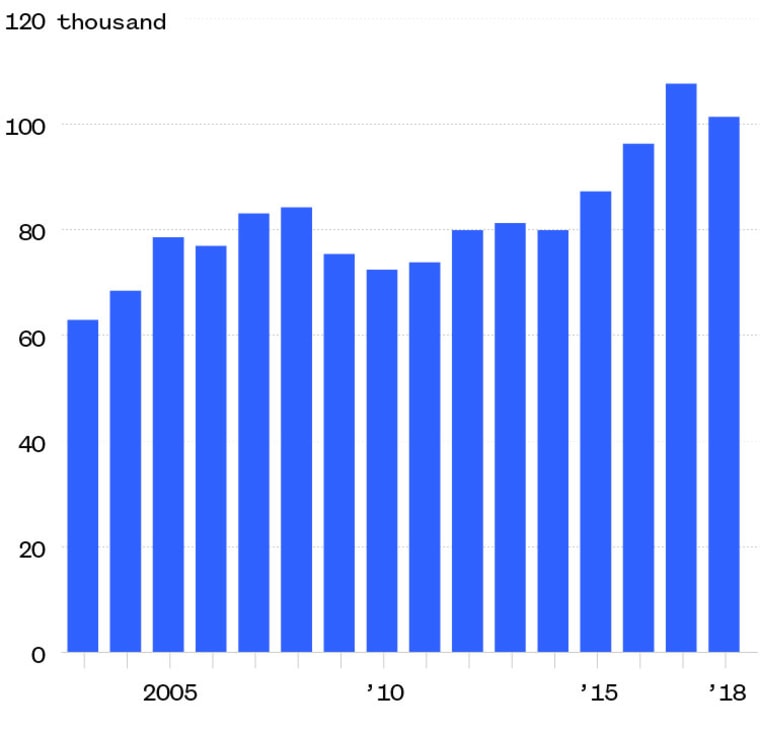

Yet the spotlight that is focused on Greenland because of climate change is also what is giving rise to a burgeoning tourism industry. In 2018, 45,739 cruise ship passengers visited Greenland, an increase of almost 20 percent over 2017, according to Statistics Greenland, an organization established by the Greenlandic government. And in the first six months of 2019, hotels across Greenland recorded more than 45,600 guests who stayed at least one night, an almost 10 percent increase from the same period last year.

Cruise ship passengers visiting Greenland

East Greenland — which once primarily attracted hardcore mountaineers and adventure-seekers — is seeing an influx of visitors, and the uptick is even more pronounced in West Greenland, where cities such as Nuuk, Sisimiut and Ilulissat are more populated and more modern.

“Fifteen years ago, climate change began to be in the newspapers, the media — ice is melting, global warming is coming, it’s getting warmer,” said Konrad Seblon, a project development coordinator for Ilulissat’s municipal government. “In that period, I think many tourists came with this thought of, ‘Let’s see Greenland before the ice melts.’”

Hotel guests who stay in Greenland

Tourism in Ilulissat also received a boost in 2004, when the town’s fjord, more than 150 miles north of the Arctic Circle and known for its icebergs, was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Unlike the more remote towns in the east, which have higher rates of unemployment, as well as of alcoholism and suicide, Ilulissat is better positioned to take advantage of the growth from tourism and industries like fishing that are booming as temperatures warm.

“It is a wealthy town, and the growth rate is very high here,” said Erik Bjerregaard, the former vice president of Air Greenland who has lived in Ilulissat for 27 years and consults for Greenland’s national tourist board. “There’s a lot of construction taking place.”

Upcoming projects include a new airport featuring a longer runway that will be able to accommodate bigger planes that fly overseas from Europe and North America. The airport — part of a proposal to expand three airports in Greenland that, until recently, languished for several years in financial limbo — could be open by late 2023, and once that happens, West Greenland could be on the cusp of mass tourism.

That prospect is creating tension in some people who stand to gain most from that shift.

Philip Holm Hansen, 36, moved from Denmark to Greenland last year to work as a guide for a tour company called Arctic Friend that operates out of Ilulissat. He and his colleagues incorporate discussions about climate change in their tours, but he said it’s difficult to share Greenland’s pristine environment with visitors without doing more damage to the very glaciers they came to see.

“It’s a difficult question,” Hansen said. “In the tourism industry, I’m helping people to get here, but by flying here, they produce a lot of CO2 and pollute more and then more ice will melt.”

‘Greenlanders are used to adapting’

As Greenland warms, some hunters who can no longer drive dogsleds on ice to hunt seals are turning instead to fishing halibut, which are swimming farther north. It’s this adaptability that has characterized Inuit culture since their ancestors arrived on Greenland’s shores, eking out a life in spite of nature’s extreme challenges.

“You have to be adaptable if you live in an environment like this,” said Juul-Pedersen, of the Greenland Climate Research Centre. “Greenlanders are used to adapting, even to very harsh conditions, and even before anthropogenic climate change.”

Despite this resilience, Kúko in Tasiilaq worries about what may be lost in the process. The kamiks that line the walls of The Red House, for instance, are symbols of a dying art — one that relies on frigid temperatures of at least minus 20 degrees Celsius to treat the seal fur and preserve its striking white color, she said.

“Because of climate change, the whiteness of the kamiks might disappear in a couple of years,” Kúko said. “That is one part of our culture that will disappear.”

And preserving this culture, with its national costumes, ancient hunting practices and deep connection to nature, means more than commemorating a traditional way of life. Rather, it’s part of Greenlanders’ identity, according to Kúko.

“Shame on the countries that are making this climate change,” she said. “I wish people will be aware all over the world how much it means for us to keep our culture.”

Sources: Statistics Greenland; Programme for Monitoring of the Greenland Ice Sheet; The National Geological Survey for Denmark and Greenland; Google Earth

Graphics: Jiachuan Wu / NBC News