Scientists say they’ve discovered one of the largest flying animals to have ever lived — a huge, fearsome reptile that ruled the skies more than 70 million years ago during the Cretaceous period.

Dubbed Cryodrakon boreas, which translates roughly to "frozen dragon of the north wind," the now-extinct predator had a wingspan of up to 10 meters, or about 33 feet. That’s roughly three times the size of the world’s biggest bird now alive, the wandering albatross, and about as wide as an F-16 fighter jet.

One of several species of extinct flying reptiles known as pterosaurs, this was one odd-looking animal.

“They’re kind of built like a giraffe,” said David Hone, director of the biology program at Queen Mary University of London and the lead author of a paper about the discovery published Sept. 9 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. “If you stood next to a giraffe at a zoo and stretched its face about twice as long and bolted extra finger joints to its front legs, you’ve basically got it. They had huge heads, huge necks and long, wispy bodies” covered in fine downy plumage like that seen on baby birds.

Cryodrakon is believed to have weighed in excess of 200 kilograms, or more than 440 pounds. Little is known about its coloration, though an illustration shows a white animal with a red splotch on its back that looks a bit like a maple leaf.

The splotch's color and shape were picked in part to acknowledge that the fossils used to identify the species were found in Canada, but Hone called the fanciful-looking color scheme "perfectly plausible" for Cryodrakon.

Hone said Cryodrakon probably lived much of its life on the ground, walking around like a modern-day egret or heron and feeding on lizards, small mammals and baby dinosaurs — “just about anything small enough to fit down its throat.”

But it was also a skilled flyer, possibly able to use its membranous wings to soar vast distances. “A journey of a few hundred or even thousands of miles shouldn’t have been a big deal,” Hone said. “I would not be at all surprised if this thing had a range across a huge chunk of North America.”

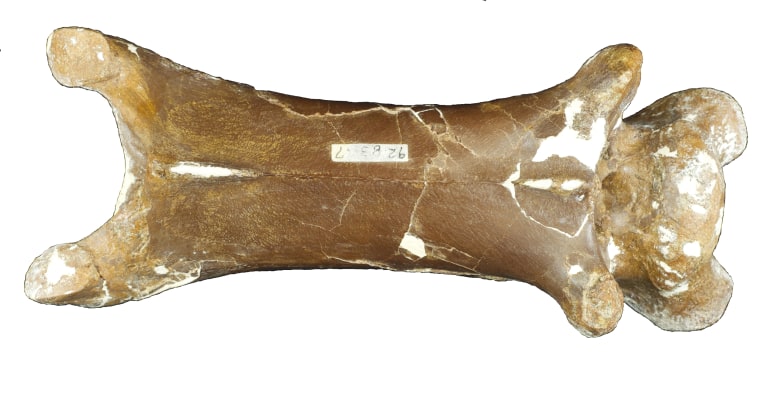

The fossilized remains used to make the discovery were found decades ago in Alberta. Scientists had long believed that the fossils belonged to another giant pterosaur species known as Quetzalcoatlus.

In a process that he described as extremely laborious, Hone and his collaborators took a close look at the fossils and others collected over the years and determined that they were different enough from Quetzalcoatlus to represent an entirely different species.

Not everyone is convinced that the new research is especially significant. "It describes some new material and names a species, but does not significantly alter our understanding of pterosaur evolution or diversity," S. Christopher Bennett, a professor of biological sciences at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas, and an expert on pterosaurs, said in an email.

But Brent Breithaupt, a paleontologist with the Bureau of Land Management in Cheyenne, Wyoming, offered a different assessment. The new discovery "provides additional information about the prehistoric past and allows us to better understand the life and times of the animals that lived with the dinosaurs, especially those that flew in the skies," he said in an email.

"One has to wonder what other unique, scientifically important specimens remain to be found in museum collections and in outcrops around the world," he added. "There is always something new to be discovered in paleontology."

Want more stories about science?

- Are we living in a simulated universe? Here's what scientists say.

- Einstein showed Newton was wrong about gravity. Now scientists are coming for Einstein.

- Scientists are searching for a new universe. It could be sitting right in front of you.

Sign up for the MACH newsletter and follow NBC News MACH on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram.