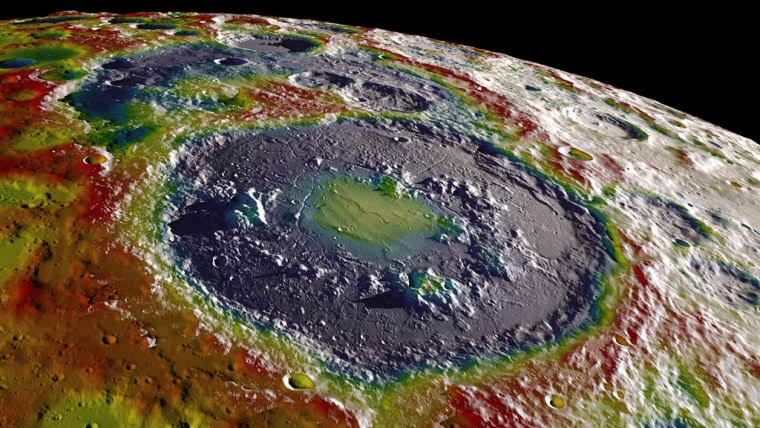

Since the discovery of water on the moon's south pole about a decade ago, scientists have wondered about the water cycle on the rocky structure's coldest region. New research provides clues as to how the water may have escaped its icy grave and splattered across the lunar surface.

NASA scientists suggest that elements from the space environment such as meteorites and solar wind that impact the lunar surface may free water molecules trapped in the lunar soil and cause them to bounce off somewhere else, according to a statement by NASA. That could potentially make it easier to reach by future astronauts, researchers said, since explorers wouldn't necessarily have to venture into the permanently dark craters at the moon's poles known to host water ice.

"People think of some areas in these polar craters as trapping water and that's it," William Farrell, a plasma physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and lead author of the new study, said in the statement. "But there are solar wind particles and meteoroids hitting the surface, and they can drive reactions that typically occur at warmer surface temperatures. That's something that's not been emphasized."

Related: Photos: The Search for Water on the Moon

Solar wind, the stream of charged particles flowing from the sun, regularly hits the moon and kicks up the water molecules, while meteoroids that impact the lunar surface can hurl small soil particles that contain ice grains as far as 19 miles (30 kilometers) from their original location, according to the study.

"This research is telling us that meteoroids are doing some of the work for us and transporting material from the coldest places to some of the boundary regions where astronauts can access it with a solar-powered rover," Dana Hurley, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, said in the statement. "It's also telling us that what we need to do is get on the surface of one of these regions and get some firsthand data about what’s happening."

One of the bigger mysteries that scientists are hoping to unravel with future moon missions is the lunar water cycle. Nearly 40 years after astronauts first landed on the moon, water was discovered in the moon rock samples brought back by the Apollo missions, dismissing previous beliefs that the moon's surface was completely barren.

The presence of water outside of the moon's cold and rough south polar region means astronauts could have better access to water molecules in the lunar soil, which makes studying the moon's water — and potentially mining the natural resource — a whole lot easier.

Additionally, the primary way scientists currently detect water on the moon is through remote sensing instruments that identify chemical elements based on the light that the lunar surface reflects or absorbs, according to NASA. Therefore, regions of the moon where sunlight is completely absent — like the permanently shadowed craters that contain water — are not exactly ideal for that type of detection.

The latest research also suggests that the space environment is not only moving water around on the lunar surface but could also be adding water to the moon. Chemical reactions between the solar wind and the lunar regolith could create water on the surface, and icy comets that crash into the moon could also boost the moon's water supply.

"We can’t think of these craters as icy dead spots," Farrell said.

The study was published July 1 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

- The Moon Loses Water When Meteoroids Smack the Lunar Surface

- How to Make Moon Water: Add Solar Wind, Tiny Meteorites, and Then Heat

- Watch Two Meteorites Hit the Moon!

Follow Passant Rabie on Twitter @passantrabie. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.