HELHEIM ICEFJORD, Greenland — We were expecting the helicopter to arrive at about 9 p.m., but as we stood on the rocky cliffs overlooking Helheim Glacier, minutes ticked by and no one could pick up the distinct choppy whir echoing up the valley.

The four of us — a scientist, a logistics coordinator, a mountaineering guide and me, an NBC News reporter — were well out of cellphone range, likely the only humans for dozens of miles. Wearing jeans and carrying a backpack containing only my laptop, notebook, a ski cap, gloves and some trail mix — the items I thought I would need for this quick reporting day trip — I felt a bit like the most unprepared character in an episode of “Man vs. Wild.” I sat on a huge rock, breathed in the crisp Arctic air and stared out at the darkening icy expanse.

As 9 p.m. turned into 9:30, we exchanged glances without saying aloud what we were all thinking: The fog, which had been thwarting our plans all day, must have rolled in again over the mainland.

David Holland, a professor of atmosphere and ocean science at New York University, pulled out a satellite phone and after a brief call to the heliport in the nearby town of Tasiilaq, he turned to me and said: “Well, it looks like you’re sleeping here tonight.”

And that’s how I ended up stuck on the edge of a glacier. We would have to camp next to the calving front of Helheim, one of Greenland’s largest and fastest-changing masses of ice.

I tried not to panic, but my mind was racing. While I didn’t feel unsafe, I did remember that as we were loading up the helicopter, Holland had casually pointed out an orange and black bag containing a shotgun — just in case he needed to fend off polar bears.

The plan had seemed simple enough. I would accompany Holland; his wife, Denise Holland, who also works at NYU doing logistics and outreach work for the school’s Center for Global Sea Level Change; and Brian Rougeux, an Alaska-based mountaineer and safety officer who has been traveling with and assisting the Hollands for several years, out to their semi-permanent campsite next to Helheim Glacier. They planned to stay for about four days near the ice mass off Greenland’s southeastern coast, as they conducted research.

“You’ll spend about an hour out there with us,” David Holland said, explaining that this would be more than enough time for me to see the instruments installed on the craggy cliffs and take some photos of the sun setting over the glacier.

The same helicopter that took the four of us out to the enormous ice field would immediately return to Tasiilaq to pick up the four other researchers on David’s team, and once they arrived, I would have my ride back into town that same evening.

It takes about 30 minutes to get out to Helheim Glacier by helicopter. After several delays because of the fog, we finally got off the ground and flew over icebergs bobbing in the bluest water I had ever seen. Though the ice rises from the water in pristine white ridges, I was surprised to see that below the water line, the light reflects an aqua so vibrant it almost glows.

After we touched down, I hiked around to explore and take photos from about 1,600 feet above the water’s surface. As I climbed over boulders and wandered along a stream, the glacier looming before me was so vast it appeared to touch the horizon. The ice field that eventually empties into the North Atlantic Ocean seemed still, masking the very activity that Holland and his team were here to study.

Helheim’s rapid retreat has been well documented. In the 14 years that scientists have been visiting and making close observations, the glacier front has backed up approximately 6 miles, equivalent to about 100 gigatons of ice flowing into the ocean.

Holland’s team is trying to understand what’s driving the staggering ice melt. This summer alone, an estimated 440 billion tons of ice has been lost from Greenland’s ice sheet — and some scientists say it could be more. It’s thought that glaciers like Helheim are melting from below, eroded by warming oceans. The complex interplay between atmospheric, ocean and ice conditions is what Holland and his colleagues were here to investigate.

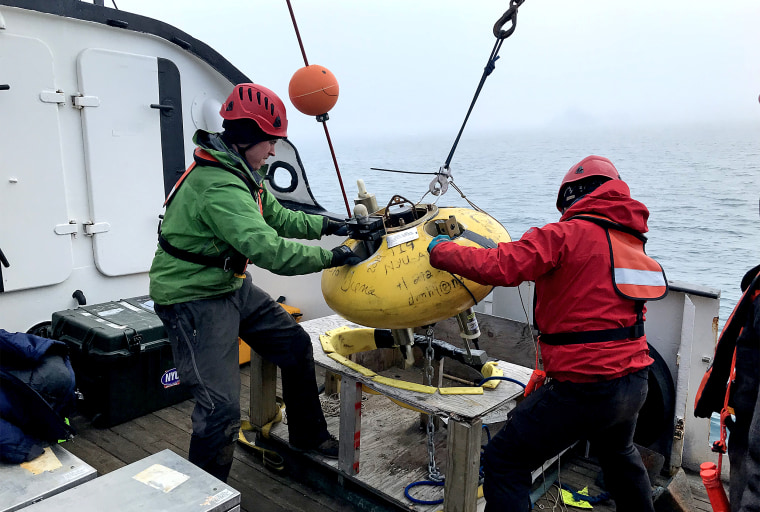

The scientists use radar and GPS instruments to monitor how the glacier’s ice moves. Several days earlier, I shadowed Holland and his team on a separate expedition that took us on a research boat through the Sermilik Fjord, which eventually ends at the mouth of Helheim Glacier. The scientists were retrieving data from seafloor-anchored buoys that spent the past year recording water temperature and salinity.

The hope was that data from the buoys, combined with measurements taken over the next few days on Helheim, would give the researchers enough clues to determine precisely why this glacier is melting as rapidly as it is, and what changes can be expected in the coming decades.

“The story is really to follow the warm water,” Holland said. “If we follow the warm water, everything else will fall into place. What we need to figure out is, how did warm water show up near ice?”

But the helicopter full of scientific equipment, not to mention the rest of the research team, was stranded in Tasiilaq for the night, so all of that had to wait until tomorrow. For now, it was dinner al fresco, cooked over an electric stove hooked up to a generator that hummed in the background.

Every so often, snapping sounds and deep rumbles echoed up out of the frozen abyss, signaling that a chunk of ice was breaking off, or calving, from the glacier. Even small pieces can make thunderous noises so loud that you stop and look. Before this trip, I had seen the Hollands’ videos of massive icebergs crashing off of Helheim, and now, as I stood less than a mile from where those icebergs had been born, I tried to imagine how deafening that must have been.

“The glacier is always talking to us,” Denise Holland said as she stirred a big pot of lightly bubbling chili.

In this spot, tucked just inside the Arctic Circle, the sun sets late in mid-August and dusk lingers far into the night. Over dinner, David Holland and Rougeux discussed priorities for the next day. Once the rest of the supplies arrived, chief among their tasks would be to set up the radar instrument, perched at the edge of a bluff overlooking the glacier’s front and encased in a white dome. It emits radio waves that bounce off the ice and allow scientists to make precise measurements of its retreat.

We were burning through valuable time that could have been spent gathering data, but as Holland repeated, there was nothing any of us could do. “You can’t control the weather,” he sighed.

As far as camping goes, it was pretty cushy. The Hollands were nice enough to let me sleep in one of their two “igloos,” spherical pods made of fiberglass that they erected to make their field research a bit more comfortable, particularly in the winter, when the rocky ground is covered in snow and ice.

Once inside the gray-colored structure, I rolled out a foam pad onto one of the two narrow sleeping ledges. It felt like I was in a spaceship or a submarine. I fell asleep quickly, thankful for the warm sleeping bag.

I awoke early the next morning to wind whipping off the glacier. The sun from the day before was blocked by a cloud-mottled sky, making for chillier conditions at the campsite. For the first time in more than 12 hours, I made contact with the outside world — a satellite phone call to my editor, who I worried would never send me on another reporting assignment after I managed to get stranded in middle-of-nowhere Greenland.

After that, all we could do was wait. The helicopter’s targeted arrival of 3 p.m. became 5 p.m., which eventually slid closer to 6:30 p.m., since Air Greenland understandably makes regularly scheduled commercial flights a priority over chartered science flights when weather causes delays.

As the hours passed, Holland detailed his plan for the days ahead, sometimes running through his mental checklist to no one in particular. The missing equipment and researchers meant changes and reshuffled priorities. I realized that what was for me, at best, an unexpectedly cool experience, and, at worst, a minor inconvenience, was much more for these scientists. To them, it meant that months — or even years — of careful planning was being derailed.

Then, suddenly, it was time to leave.

“When I was in Antarctica, we had a saying: When a helicopter lands, you get on it. You don’t ask where it’s going,” Holland joked.

I didn’t hesitate to take his advice when one finally showed up. But as the helicopter’s rotors spun to life and we floated up into the sky, I found myself missing the peace, solitude and absolute splendor of Helheim Glacier.

Sign up for the MACH newsletter and follow NBC News MACH on Twitter and Facebook and Instagram.