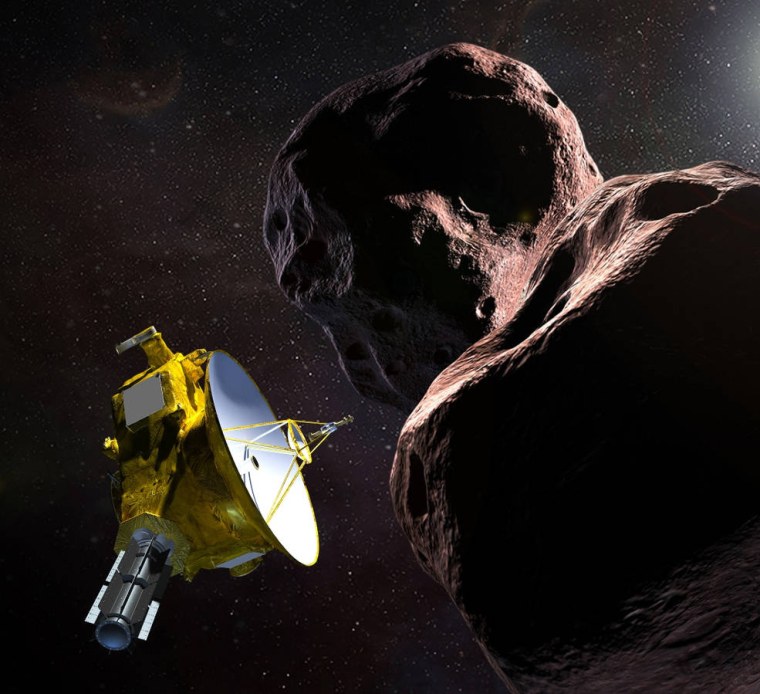

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft notched a second triumph in its belt, passing close by a second object two-and-a-half years since it passed Pluto. At 12:33 a.m. ET on New Year’s morning, the spacecraft passed Ultima Thule, a Manhattan-sized rock a billion miles farther out and essentially straight ahead from its Pluto passage in 2015.

A thousand cheering scientists and families awaited confirmation at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, that the spacecraft survived and recorded data.

Though the closest point of the flyby, only 2,200 miles above Ultima Thule’s surface, occurred just after midnight, the spacecraft was pointed at the object for a few more hours with its antenna, rigidly locked to the spacecraft body, pointing away from Earth. And once the spacecraft rotated to send a burst of housekeeping data back to NASA’s Deep Space Network radio telescope in Madrid, the signal then took six hours and seven minutes at the speed of light to reach Earth. Comparing that travel time with the eight minutes it takes light from the Sun to reach Earth or the slightly over one second that it takes light from the Moon to reach Earth shows how far away the encounter with Ultima Thule was.

The burst of data sent Tuesday morning was merely to check that the spacecraft was still functioning — among other things not having been destroyed by running into a dust particle at 32,000 miles per hour. The audience at JHUAPL cheered as they watched the control room on a video feed as system after system reported “green,” meaning success. And one signal showed that the Solid State Recorder’s computer memory was full, indicating that the spacecraft took its quota of data.

At a press conference an hour later, Principal Investigator Alan Stern of Southwest Research Institute of Boulder, Colorado, led a team reporting on what is known, though the images from Tuesday won’t be available until Wednesday.

“I don’t know about you, I’m liking this 2019 thing so far,” joked Stern. Mission Operations chief Alice Bowman reported on the data successfully received via the Madrid station of the Deep Space Network.

Stern summarized his team's accomplishments by saying, “They scored 100 on the test.”

The last blobby picture sent back before the flyby — the best available so far — showed that Ultima Thule is 35 by 15 kilometer, with a blurry peanut shape, so it is either “bi-lobate,” with a different size for each lobe, or it could be two objects whose images blurred together.

As project scientist Hal Weaver of JHUAPL described, the series of images taken showed its rotating in the manner of a propeller, in which we see the same side throughout rather than seeing a periodic change in brightness over time. At present, both a 15-hour period and a 30-hour period fit the blurry observations that they have seen. The next images will reveal the actual situation.

The object Ultima Thule, the nickname for 2014 MU69, was discovered by Marc Buie of Southwest Research Institute in 2014, in an extraordinary search among millions of stars imaged for the purpose with the Hubble Space Telescope. The position was refined by a series of so-called stellar occultations, as the object passed in front of a distant star as viewed by NASA-sponsored expeditions to Argentina, South Africa and Senegal.

At only 1000 bytes of data transmitted per second whenever the Deep Space Network’s antennas are available to this mission among the others it is monitoring, it will take 20 months for all the data to come back. The highest-resolution images won’t be received on Earth until February, but this week’s data is expected to reveal the basic structure of Ultima.