Using electrodes and artificial intelligence, scientists in California have built a device that can translate brain signals into speech. They say their experimental decoder could lead ultimately to a brain implant that restores the ability to speak to people who have lost it as a result of stroke, traumatic brain injury or neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease.

“This is an exhilarating proof of principle that with technology that is already within reach, we should be able to build a device that is clinically viable in patients with speech loss,” Edward Chang, a professor of neurological surgery at the University of California, San Francisco, and the senior author of a paper describing the technology, said in a statement.

For their research, Chang and his collaborators recorded the brain activity of five epilepsy patients (who already had brain implants as part of their treatment) as they read aloud a list of sentences. Then a pair of neural networks — artificial intelligence algorithms specially designed for pattern recognition — began the decoding process. They first used the brain signals to predict the instructions being sent to the lips, tongue, jaw and throat to produce the words. The second turned the predicted movements into synthesized speech produced by a computer.

To test the intelligibility of the computer-generated speech, the scientists had native English speakers listen to the sentences and transcribe them word by word, choosing from a list of possibilities for each word. The results varied depending on how many options transcribers had to choose from, but on average, the listeners were able to correctly identify 70 percent of the words. When given 25 options per word, they got 69 percent of the words correct; with 50 they got 47 percent correct.

Other scientists lauded the research for its focus on mouth movements needed to produce speech rather than on specific words or sounds. The approach allowed them to tap into a rich vein of research on turning thought into movement, Ander Ramos-Murguialday, who leads a brain-machine interface lab at the University of Tübingen in Germany, told NBC News MACH in an email.

Brain-machine interfaces translate brain signals into actions, like moving a cursor on a screen or even flying a drone. They’ve previously been used to help people with paralysis type with their brains — albeit at only eight words per minute, compared to about 150 for speech-recognition systems.

The researchers’ approach could also quell fears that an individual’s private thoughts might be broadcast to the world, said Jane Huggins, director of the University of Michigan Direct Brain Interface Laboratory in Ann Arbor, who was not involved in the research.

“Decoding the brain signals related to the mouth movements that create speech has the advantage of only decoding things that the person intended to say,” she said in an email. “So it minimizes privacy concerns that could occur with decoding other types of brain activity.”

But that same reliance on mouth movements leaves it unclear whether the decoder can help those who might benefit the most from it: people who can’t move their mouths as a result of stroke, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or other conditions.

“The main limitation of these results is that they cannot be applied, as they are now, to patients without articulation,” Ramos-Murguialday said in the email, referring to the ability to produce speech. In other words, since the participants in the new study could all speak normally, it’s unclear how the algorithms would work on the brain signals of people who can’t.

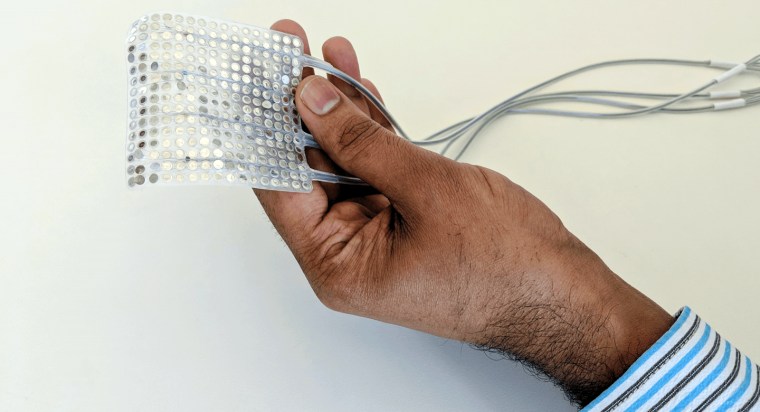

There’s also the question of applying the electrodes. Like many brain-computer interfaces, the experimental decoder uses sensors applied directly to the brain. Unless scientists figure out an alternative, that means the procedure to implant the decoder will require brain surgery.

Despite such concerns, Ramos-Murgulalday called the work "a very promising step" toward a future in which people with speech difficulties can easily communicate in real time.

Josh Chartier, a UCSF graduate student and a co-author on the study, thinks so, too.

“People who can’t move their arms and legs have learned to control robotic limbs with their brains,” he said in a statement. “We are hopeful that one day, people with speech disabilities will be able to learn to speak again using this brain-controlled artificial vocal tract.”

Want more stories about science?

- Chinese scientists insert human brain gene into monkeys, spark ethical debate

- Israeli scientists create world's first 3D-printed heart using human cells

- Scientists say brain implant may be the key to beating addiction

SIGN UP FOR THE MACH NEWSLETTER AND FOLLOW NBC NEWS MACH ON TWITTER, FACEBOOK, AND INSTAGRAM.