Former astronaut Chris Hadfield is not afraid of death.

That might seem surprising, given the safety record of human spaceflight. To date, 565 men and women have ventured into space, and 32 have died while going up, coming down or preparing for flight. Statistically speaking, an astronaut’s odds of dying on the job are more than 1 in 20.

That was a stark reality for someone like Hadfield, who spent 35 years as a military pilot and astronaut before retiring from the Canadian Space Agency in 2013. Hadfield flew into Earth orbit three times, including two trips aboard the space shuttle and one aboard the troubled Russian Mir space station.

For his last trip into space, in 2012, he spent 144 days as commander aboard the International Space Station.

Maybe you’re among the 41 million viewers who’ve watched the video of him covering David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” while floating weightless in the station's seven-windowed cupola.

He sure doesn’t seem afraid in the video. In fact, he looks utterly serene.

A frequent question

Astronauts hear the question all the time: When you strap in atop an enormous stick of explosive fuel and then shoot into the breathless vacuum of space, aren't you afraid to die?

Hadfield’s answer is always “no.” To him, the question is based on a flawed premise: “In common life, we make fear and dangerous synonymous, but they're not,” he says. They only seem that way because few people prepare extensively for dangerous things, he explains, but being prepared is exactly what astronauts do through years of intense training.

“The greatest antidote for fear is competence,” Hadfield continues. “If you're spending 10 years preparing for one launch, then hopefully by the time it arrives you’ve changed your skill set such that a launch is no longer foreign and unknown. In fact, it's the opposite. It's exhilarating.”

Like riding a bicycle

As Hadfield tells it, astronauts regard space missions the way most of us regard riding a bicycle. “When you don't know how to do it, it's scary,” he says. “It makes little kids cry. But eventually you master the skills. Then you can ride the bike, and it’s no longer scary.”

That mindset pretty much holds true across the astronaut corps. It helps explain why one seldom hears astronauts talk about fear, or about the body count in their line of work.

Instead, they focus on the skills they’ve acquired floating in the simulated zero-g world of the Neutral Buoyancy Lab at the Johnson Space Center in Houston; learning high-speed maneuvers while piloting a T-38 jet; or huddling inside NEEMO, an undersea habitat off the Florida Keys. (Hadfield was a commander there, too.)

NASA uses such training exercises to prepare astronauts for just about every foreseeable situation. Of course, some of the problems that inevitably crop up are things that no one anticipated.

There was the time when faulty sensors prevented Hadfield’s space capsule from docking with Mir, forcing him to improvise a way in. And the surreal incident in 2013 when Italian astronaut Luca Parmitano’s helmet sprang a leak and he nearly drowned during a spacewalk outside the ISS.

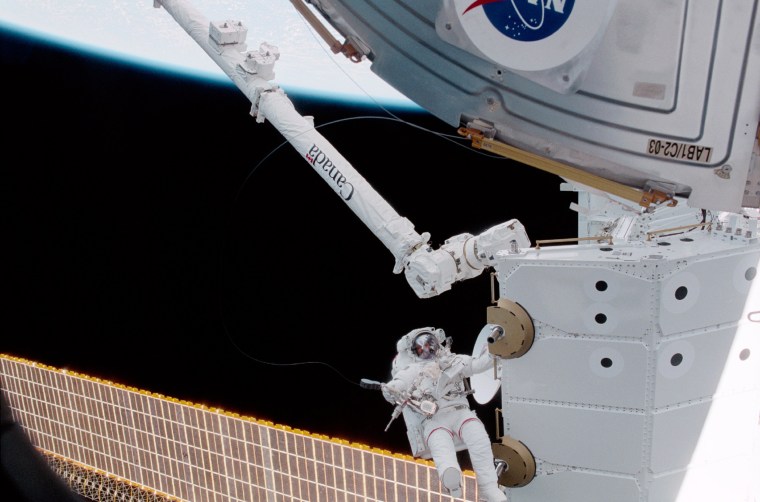

Hadfield had a suit mishap of his own on a spacewalk in 2001: A bit of chemical defogger that had been applied to his helmet visor got into his eye, causing him to tear up so badly that for a few scary moments he was unable to see.

On Hadfield’s final expedition, the ISS sprang an ammonia leak. “Ammonia is a very nasty chemical that you don't want to get inside the ship,” he says matter-of-factly. “We had to do an emergency spacewalk on one day's notice to go out and fix a system that was leaking.”

Fighting risk with expertise

Hadfield sees such incidents not as exceptions to his bicycle metaphor but as evidence in support of it. The “competence” he talks about refers not to following a specific set of instructions but to a general approach to problem solving that kicks in whenever it’s needed.

As for the ammonia leak, “it’s what every member of our crew had been preparing for, for a decade or more: How to get ready for something that is going to push you to your limits, physically and mentally and maybe even tactically, and then summon the reserves to execute it properly,” Hadfield says. “That’s the life of an astronaut encapsulated.”

Hadfield and his crewmates quickly fixed the leak. Nobody got sick, and the incident barely even made the news.

Of course, not all the crises astronauts face are manageable. Some end like the Challenger and Columbia disasters, both of which killed entire space shuttle crews. Surely that must spook the astronauts, right?

Hadfield acknowledges Challenger and Columbia as proof that death is always a possibility. But instead of the loss of life, he and his fellow space-flyers focused on positive lessons from the disasters. “We said, ‘What can we learn from these horrific events so that spaceflight will be safer in the future?’”

In other words, don’t worry about things you can’t control. Keep working to address problems up to the last possible moment. If you die, you die. Ultimately, death is something that lies beyond an astronaut’s control, so in some sense it’s irrelevant. That mindset is part of what NASA selects for, and part of what astronauts train to achieve.

The one fear that astronauts cannot vanquish, no matter how much training and mental discipline they bring to bear, is the fear experienced by their friends and family. Yet even here, Hadfield treats the matter as a series of variables to be managed.

“I went so far as to invite my wife to attend one of the simulations in which one of the crewmembers dies during launch or on orbit — what we call a ‘contingency sim’ — because I wanted her to see how the process would react to me being killed,” Hadfield says.

The mortal leap to Mars

If the world’s space agencies and emerging private ventures like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic keep pressing farther into the solar system, it’s inevitable that some of those contingency simulations will come true.

Life aboard the ISS is dangerous, but Earth is just 240 miles away. Rescue or evacuation is always an option. On a moon base, the risks would be greater, and greater still for a mission to Mars. Once the hatch closes, a Mars crew will be on their own for a year or more.

“Either someone's going to have to be willing to take a huge risk of failure where the crew is killed, or we're going to have to spend a huge amount of money on reliability and predictability and redundancy to increase the probability of a safe return to Earth,” Hadfield says.

He can’t vouch for the equipment, but he’s almost preternaturally confident in the crew. As he sees it, this is just another application for the formula of intense competence that negates fear and minimizes danger.

“It's the trade-off of risk, always. What skill sets don't we have yet? What are the probabilities of things going wrong?” Hadfield ticks off the requirements like he’s making a grocery list. “Let's try and make the best compromise we can. Just as for the space station crews, so we'll do the same for Mars.”

Want more stories about spaceflight?

- So you want to be a space tourist? Here are your options

- This luxury space hotel could be up and running in four years

- NASA's Deep Space Gateway seen as key to bold plan for Mars and beyond