WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court has long painted itself as a safe space in a country dominated by political partisanship, where the law and the Constitution rule. But data from recent years puts some weight behind the critics who argue that the highest court in the land has taken on a more partisan cast.

Start by looking at who actually gets nominated and seated on the court. Again, partisan politics aren’t supposed to figure into who sits in those nine seats across from the Capitol, but in recent elections, the ability to get justices on the court has become a big part of presidential politics.

In 2016, Senate Republicans refused to even hold a hearing for President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland, now the attorney general. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said the voters should decide who filled the seat with their presidential votes, and it sat empty for more than a year after Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016.

Four years later, when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in September 2020, President Donald Trump and Senate Republicans hurried to compete the nomination and confirmation of Justice Amy Coney Barrett before the presidential election and argued that it was Trump’s right.

That’s just recent history, of course. But going back over time, Republican presidents have held a decided advantage in placing people on the court.

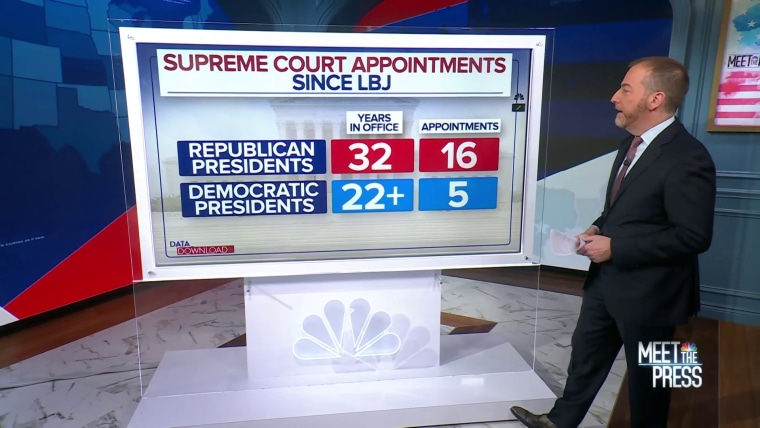

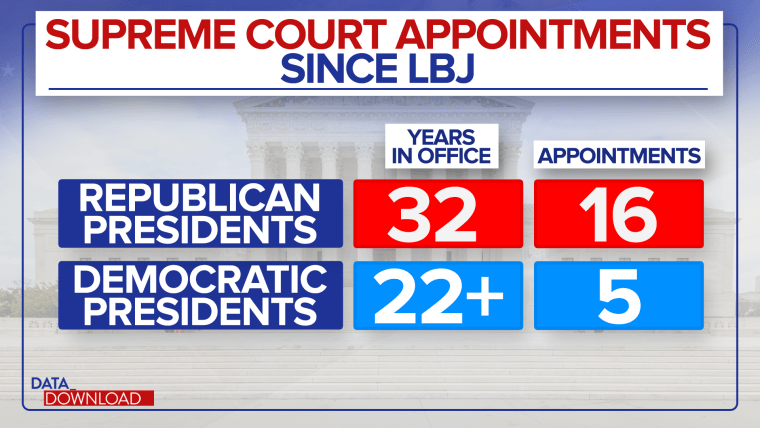

Since Lyndon Johnson left office in 1969, Republicans have held the White House for 32 years and have nominated and confirmed 16 justices. Democrats have held the White House less, only 22-plus years, and they have put only five justices on the court.

In other words, since LBJ, Republicans have held the White House for 59% of the time, but they have been responsible for placing 76% of the justices on the court. Democrats have held the White House 41% of the time, but they have been behind only 24% of the successful nominations.

There are many reasons behind the discrepancy beyond the last few presidencies. President Jimmy Carter was in office for four years and didn’t get a Supreme Court vacancy. George H.W. Bush was a one-termer who got two justices.

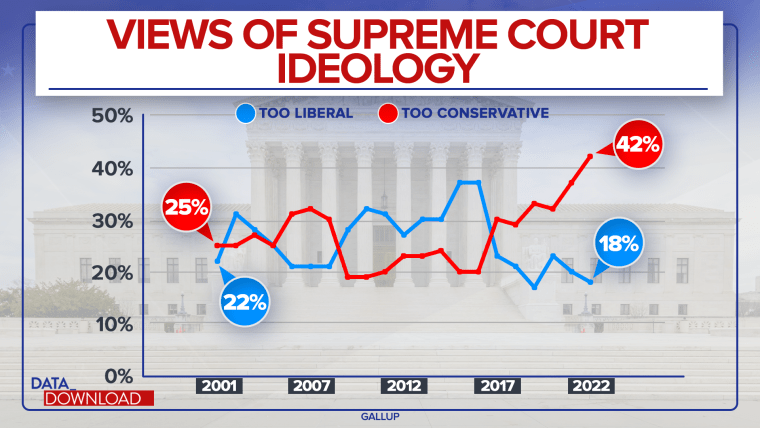

That math, combined with some important cases in recent years, seems to have shifted how Americans view the court. The number of adults saying the court is “too conservative” hit a record high last year, according to Gallup.

More than 4 in 10 Americans said the court was “too conservative.” Only 18% said the court was “too liberal.” Another 38% said the court’s ideological lean was “about right.”

The numbers marked not only an all-time high for the “too conservative” number — they also marked the first time that “about right” didn’t have a plurality of the national sentiment. That’s a significant development. It suggests the attitudes really are different now from what they have been in the last 20-plus years.

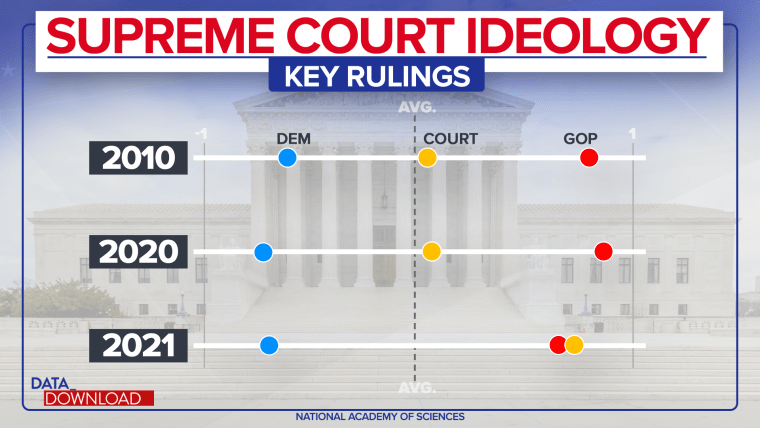

And other data suggests the court’s rightward move is about more than appearances. It’s about actions. In a study and a paper for the National Academy of Sciences, three academics weighed how U.S. adults felt about 10 to 12 key cases before the court in 2010, 2020 and 2021 and compared that to how the court voted in those cases. The movement of the court’s “center” was apparent.

In 2010, the survey asked people about 10 cases and whether they considered themselves to be Democrats or Republicans. When the results were tallied, Democrats wound up choosing one set of outcomes and Republicans chose a different set. The court was close to the middle between the two groups.

In 2020, they repeated the exercise with a new set of cases from that court term. Democrats and Republicans again wound up with different favored outcomes, and the court’s rulings were, again, largely in the middle between the two.

But the numbers shifted in 2021 after Barrett replaced Ginsburg. The distance between where Democrats and Republicans stood on the cases in that term looked similar to other years. But the court’s rulings had shifted far to the right — even a little further to the right than the Republicans’ views on those cases.

Those are decisions from one year, of course, and they could be an aberration — maybe a specific set of cases that led to more Republican-leaning positions. But there is further evidence of that conservative lean the next year, in 2022, particularly with the Dobbs decision, which eliminated the federal protection for the right to abortion that had existed for almost 50 years.

To be clear, the dataset doesn’t mean the 2021 rulings were more correct or more wrong than in other years. But going by this measure of relative ideology, the court’s 2021 rulings definitely tilted more toward Republicans than previous years. The authors of the study estimate that the ideological “center” of the court in 2021 moved from Chief Justice John Roberts to Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

That’s good news for Republicans. It’s the result of both coincidental timing and a concerted effort to change the court’s composition. But in a country that is closely and intensely divided, it can also present challenges.

The center has long been a key place to get things done and keep heads cool in the U.S.’s two-party system — but that center is a pretty empty place in American politics these days. Having the Supreme Court firmly on one side of the ideological chasm seems unlikely to help the nation find middle ground or build the people’s faith in the institution and in Washington.