WASHINGTON — This coming week marks one year since the word "lockdown" started to become synonymous with Covid-19 in 2020. As events and sports seasons and, ultimately, work in offices were suspended and postponed, the scale of the pandemic became clear.

The numbers around the virus today tell the story of a different kind of economic slowdown, one that took an especially large toll on one sector of the economy. Now, as vaccination rates rise, there is a lot of optimism that the economy could be getting a lot healthier in 2021.

But anyone planning for a quick economic turnaround may be surprised. A long list of data points raise some serious questions about when a healthy economy will arrive, or what it will even look like.

The ground shook last March and in a few days, life in the United States changed fundamentally as Covid cases began to rise sharply.

On March 11, the NBA suspended its season after a player on the Utah Jazz tested positive for the virus. The next day, Major League Baseball ended Spring Training and announced it was pushing back the start of its season. That same day the NCAA canceled its 2020 basketball tournaments for men and women. A few weeks later, the Olympics would postpone their quadrennial games.

The result was not just a lot of canceled and postponed events, it was a lot of flights not being taken and hotels not being filled and meals not being eaten in restaurants. And the biggest hit may have come in the days and weeks after when employees began shifting to "remote work."

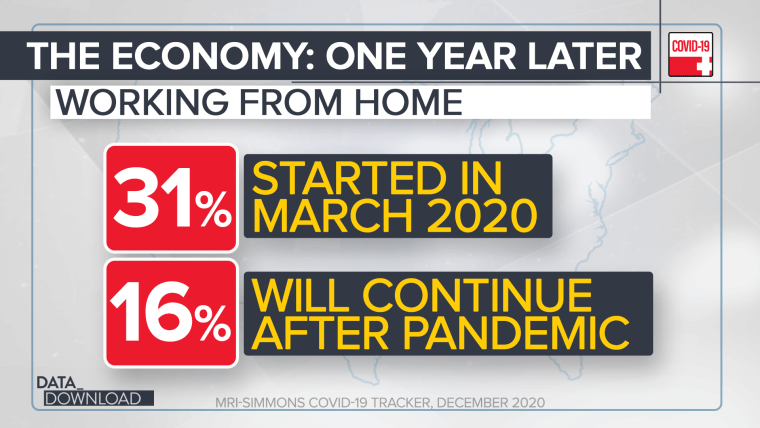

In total, 31 percent of U.S. adults found themselves working from home due to the Covid outbreak in 2020, according to the MRI-Simmons Covid-19 Study. Many of those workers are still calling their home their office. Those people aren't visiting the restaurants and coffee shops around their former workspaces. Their old office buildings don't need to be cleaned. If they took the train or bus to work, they aren’t anymore.

All those changes, along with the larger impacts of reducing or barring indoor gatherings, have led to some huge hits on people who work in leisure and hospitality.

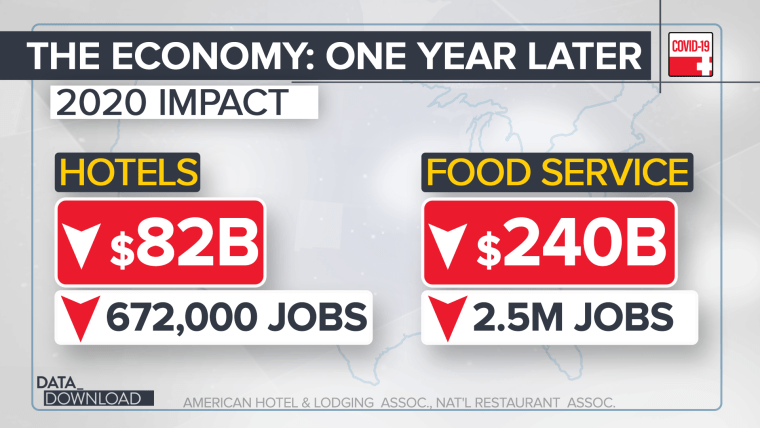

In January, the National Restaurant Association announced its restaurant and food service sales were $240 billion below expectations in 2020 and jobs in the industry were 2.5 million below where they were before the pandemic.

The numbers in the hotel industry don’t look much better. Hotel room revenue was down some $82 billion below expectations in 2020, according to the American Hotel and Lodging Association. There were more than 670,000 jobs lost in the industry.

And if you zoom out to look as the economy as a whole you can see just how significant the losses have been.

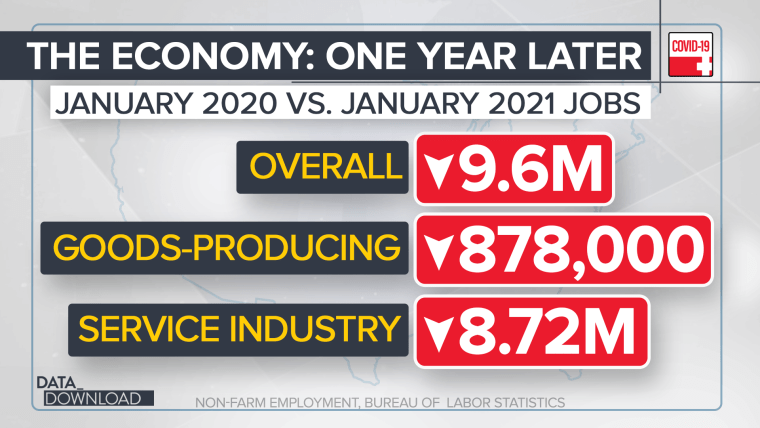

Unemployment is up across the board, of course. But when you consider the number of people who are actually employed this January compared to a year ago, you see the broad outlines of a deep service economy recession in the United States.

In total, about 9.6 million fewer Americans were employed this January compared to a year ago, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s not a great number and it suggests any recovery is going to take some time, but the distribution of those losses is remarkable.

Fewer than 1 million jobs, about 878,000, have been lost in good-producing areas, such as manufacturing and construction. Meanwhile, more than 8.7 million employment losses have come in service-producing jobs – areas such as leisure and hospitality, professional, education and health service jobs.

Those service losses are driven by fewer people traveling, eating out and, in essence, doing a lot of things outside their homes – everything from getting haircuts to taking in movies. They are not "remote work" jobs for the most part. They are in-person jobs that require a mask or, maybe, a vaccine.

That's one reason why things are looking up in 2021, at least for now, but there is also a lot of reason for uncertainty. A lot of the big events of 2020 are back on in 2021, but in a somewhat diminished state.

For instance, there will be an NCAA basketball tournament in 2021, but the men’s games will all be held around Indianapolis in arenas filled to just 25 percent of capacity. Major League Baseball is moving forward with its season, but when fans will fill seats and how many are very unclear.

And while people may soon be able to "go back to work," a lot of people aren’t sure they want to. Of those 31 percent of adult workers who are presently working from home due to Covid, only about half say they plan to go back to work. (Of course, their employers may have other ideas.)

To be clear, there is a lot of good news on the Covid front, but not enough, at least not yet, to quickly turn around those miserable employment numbers.

And beyond timing, there is a bigger question about Covid’s lasting influence. How much has the pandemic changed the way we live in more structural ways?

This size and shape of Covid’s economic impacts should serve as a reminder that the vaccine is really just the beginning. Even after everyone's arm is poked, it may take some time before we understand what the new economic normal really looks like.