Discussing critical race theory is hard. There's critical race theory, an academic movement dating back to the 1970s that pioneered ideas like "structural racism" and "intersectionality." And then there's "critical race theory," which has become a popular catch-all term on the right for discussions around race that activists consider offensive. And the distinction between the two is often lost in the national shouting match that's played out everywhere from from the White House to local school boards.

Sociologist Victor Ray was on his way to teaching his intro class on critical race theory when he saw the news that then-President Trump was banning CRT from federal workforce training. With the public conversation around it growing increasingly distorted, he decided to provide people hearing about it for the first time with a primer. His new book, On Critical Race Theory: Why It Matters & Why You Should Care lays out the origins of the movement, its most prominent concepts and thinkers, and how he and other academics use its ideas to research and explain racial discrimination.

We talked to Ray, the F. Wendell Miller Associate Professor at the University of Iowa, about his book. Our conversation is below, edited for length and clarity.

Q: What's your best short definition of critical race theory for someone learning about it for the first time?

Ray: It's the official body of legal scholarship that tried to explain the political backlash and legal backlash to the civil rights movement. You had all of these major civil rights victories in the late 1960s and even the 1950s that by the Reagan era were being undermined. And so a group of legal scholars, like Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw, and other folks, got together to try and explain why the law was inadequate, or why maybe the legal victories of the 60s weren't a permanent victory. They drew on history and social sciences to critique the way both liberals and conservatives approached it.

Critical race theory also became kind of a broad approach and framework for thinking about race. It criticized things like individual notions of prejudice and discrimination versus structural racism, and replaced biological notions of race with the idea that race is a social construction, and social factors are more important than individual ones.

Q: You mention "structural racism" in contrast to individual prejudice. What does structural racism mean?

Ray: A more mainstream "racism" is individuals not liking someone because of their racial background. It's a cop choosing to choke someone to death with their knee for nine minutes. The idea here is that it is based on some sort of individual disposition of the cop.

But what structural racism says is, look, individual prejudice is important and we don't necessarily want to discount that, but let's think about what empowered the cop to get his knee on George Floyd's neck in the first place. And if we do that, it's a whole history of laws that allow cops to racially profile in some cases, to stop and frisk. It's a history of cops coming out of union busting and slave patrols in the U.S. South. It's a history of laws that provide police officers with impunity.

There are individuals within that system that have all different kinds or varying levels of personal animosity, or no personal animosity. If we think about "stop and frisk," I genuinely believe that there are a lot of people of color, police officers, who join the force, who say "I'm going to make it better," and they genuinely try to make it better.

But if they follow the rules of that system, they're going to disproportionately stop and frisk Black and Latino men. We have the data on that. Being part of a system means that, not always, but sometimes, you might contribute to that system or be complicit in its reproduction.

Q: You write that “Critical race theorists reject the mythology of racial progress." What is that mythology and why is it harmful?

Ray: The mythology is that things are always getting better around race. We had slavery, we fought the Civil War, that fixed that. Then Jim Crow happened, civil rights movement fixed the problems of Jim Crow. President Obama got elected, we're post-racial.

Following each of those massive important movements for freedom and justice, they were met with intense white backlash. And in some cases, the backlash created new creative means of disenfranchising black folks in particular, and people of color more broadly.

Look at what’s happening now around the country with massive voter disenfranchisement. The number of laws passed since 2020, folks taking over local elections, and really trying to disenfranchise people through those mechanisms.

So critical race theory focuses not just on the bright side, of American racial history, but it points out that there have always been people opposed to racial progress. And oftentimes, those folks are very, very effective.

Q: One related idea you devote a chapter to is the late professor Derrick Bell's theory of "interest convergence," or the idea that progress towards equality happens primarily when it suits white people's material interests, rather than because of some broad moral awakening.

Ray: Derrick Bell argues that when we look at the Civil War, or we look at the Civil Rights Movement and Brown v. Board of Education, that those definitely disadvantaged some white Americans, but on the whole, they tended to benefit at least enough non-white folks and white elites that their interests temporarily converged.

Bell talks about Brown v. Board of Education as sort of the most important example of this. It's often hailed as the apotheosis of American racial progress.

But Bell says, look, the morality of this didn't change, folks always knew that segregation was immoral. What actually changed was America's geopolitical position. The Soviet Union was effectively using America's racism in anti-American propaganda in order to get proxy states on their side. And the State Department recognized this, and a number of politicians recognized this, and came out in support of the winning side in Brown.

Q: If the thesis is that a critical mass of white voters inevitably tend to push back against necessary change, is real change possible?

Ray: I guess it depends on what you mean by real change. I would never say that the Civil War or the end of Jim Crow didn't make real substantive change. But I think there's also real substantive backlash, there are counter-movements to that change that are also very important.

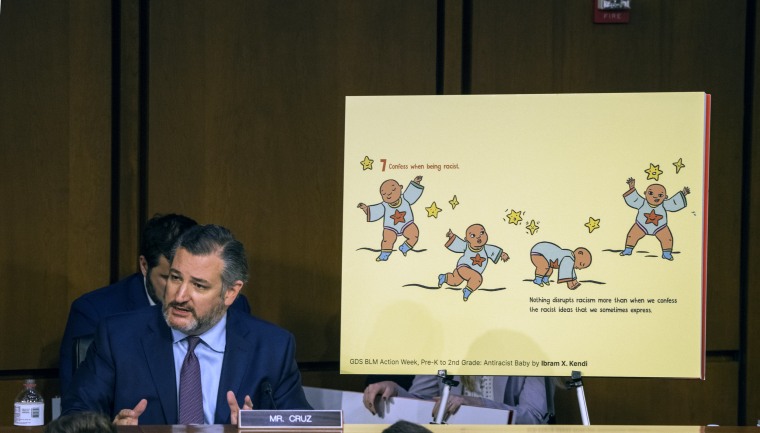

Ibram X. Kendi is very clear that he's not a critical race theorist, but he has this line that I think about quite a bit: Racial progress has happened in U.S. history, and racist progress has happened.

I think a lot of folks when they talk about racial inequality, they want a kind of final policy that's going to end it. Critical race theory is saying, look, folks will continue to fight, and realistically, you're going to have to continue to fight too if you're on the side of racial justice. That might not be hopeful, but I think it's purposeful.