WASHINGTON — The holiday break is here for K-12 students, and for many schools the pause in instruction means it’s time for serious questions about how they will go forward in 2022. A return to normal (or closer-to-normal) schooling this fall has led to parent-teacher tensions, combative school board meetings and big staff shortages across the country.

Much of the anxiety centers on how to handle Covid-19, and in some districts the staff shortages have become so pronounced that there is a fear that some teachers and other staff members may not return when schools are back in session next month.

That’s a problem, because most schools were already starting in a tough spot this fall.

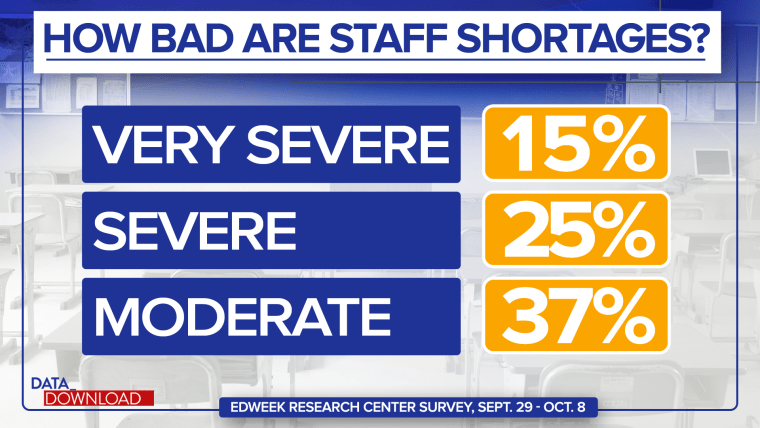

In October, Education Week released a survey of principals and district administrators that found deep shortages in staffing.

Thirty-seven percent of those surveyed said staffing shortages were “moderate,” while 25 percent said the problems were “severe” and 15 percent more said they were “very severe.”

Add it up and that’s 77 percent of those surveyed who said staffing shortages were creating notable impacts, which shows how deep the problems were this fall.

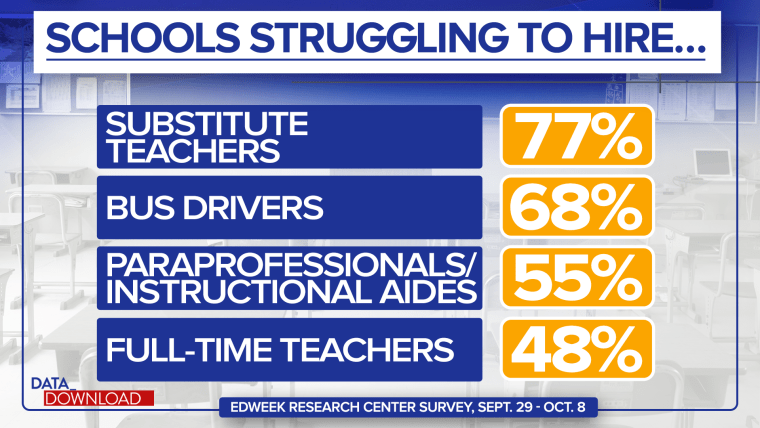

Where were the problems being felt? Pretty much across the board, according to the Education Week survey.

The shortages were most acute among substitute teachers — 77 percent of districts or schools said they had struggled to hire enough to fill their needs. That’s probably not a surprise; Covid and Covid testing mean there are likely to be more days than normal when regular teachers can’t do their jobs.

And substitute teachers are one area in which schools could be hit twice as hard — by an increased need for more substitutes and by increased difficulty finding people to do the job as others have been reluctant to rejoin the labor force.

In other staffing areas, 68 percent of those surveyed said their schools or districts had struggled to find enough bus drivers. More than half of those surveyed, 55 percent, said they were having difficulty finding teacher aides.

And nearly half, 48 percent, said their schools or districts were having difficulty finding enough full-time teachers.

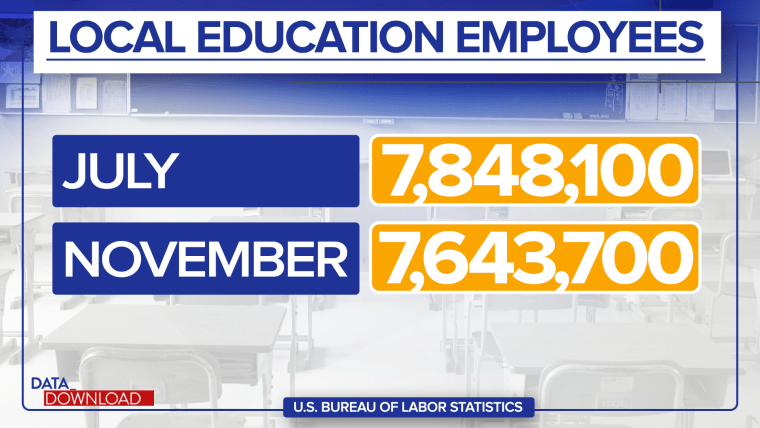

In short, the “Great Resignation” seems to have hit schools across all positions, as seen in data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS.

Since July, the number of people employed in education in local governments has declined by more than 200,000. Over the last year, peak employment in education at the local level came in July. That’s the middle of the summer, as schools are figuring out staffing for the next year. The number has dropped every month since then, during the school year.

And the July peak number, 7.8 million, was still 200,000 below the figure in February 2020, just before the pandemic hit. If the February 2020 number, 8 million, was the true measure for where local school employment should be, the figure last month is off by 400,000 employees.

Perhaps more concerning, all those shortages mean the work at schools is harder, as well. Regardless of how many teachers there are in each school, the number of students to be taught doesn’t change. Classes must be bigger, or teacher class loads have to grow. Bus routes don’t disappear just because there’s a pandemic. Drivers must simply drive more.

There are a lot of increased pressures in schools, and they may be discouraging people from seeking jobs as teachers, aides and bus drivers, which in turn makes pressures worse, creating a kind of negative feedback loop in education employment.

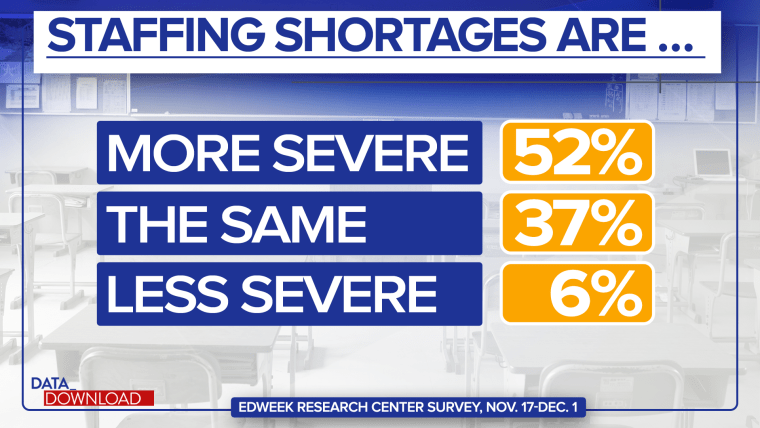

An Education Week poll last month found that districts are feeling the pinch, maybe even more dramatically than shown in the BLS data.

The poll found that more than half of those surveyed, 52 percent, said staffing shortages had gotten more severe in their schools or districts since the school year began. Only 6 percent said the problem had improved.

All those surveys, of course, were conducted before the arrival of the omicron variant of the coronavirus, which is upending what we know about Covid just as the holidays hit. What we learn about the omicron variant in the new few weeks could change when students return to school and what classes look like when they do.

But the bigger message is more sobering. The Great Resignation isn’t hitting all industries in the same way. The numbers suggest that a deep and fundamental disruption is rippling through the education system and that regardless of what we learn about Covid and the omicron variant in the next few weeks and months, getting things back on track is probably going to take some time.