It is a loathsome truth about incarceration in America that uncovering LGBTQ history means searching through the prison records of forgotten queer people.

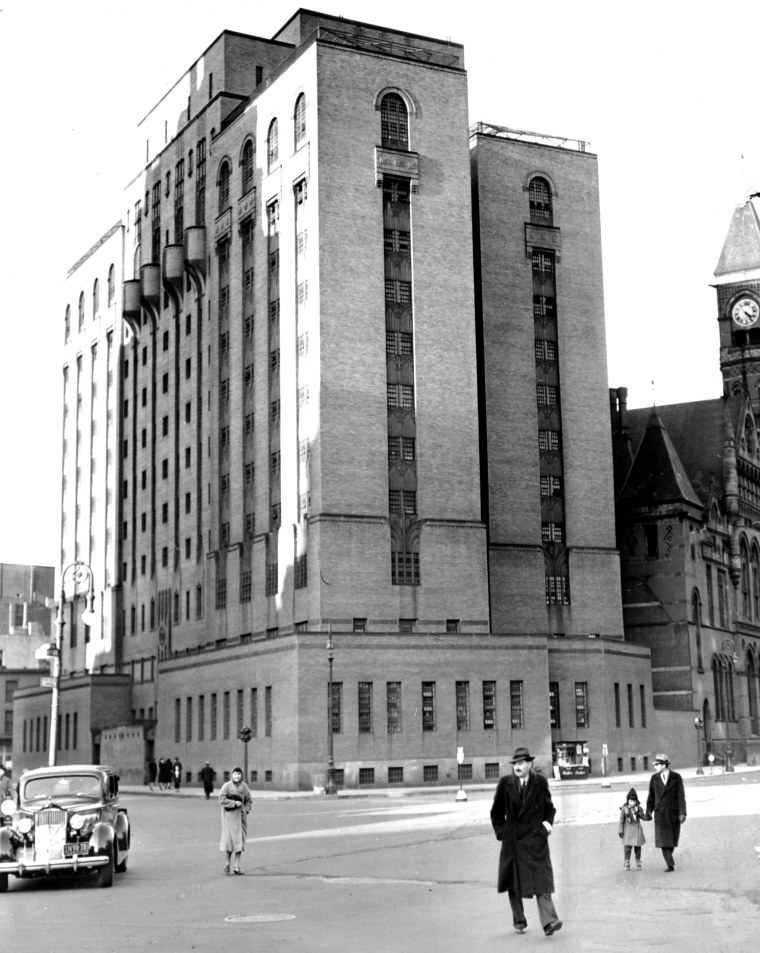

Historian Hugh Ryan undertook such a mission, focusing on the Women’s House of Detention, a prison that stood in New York City’s Greenwich Village neighborhood from 1929 to 1974. The now demolished 11-story art deco building was located down the street from the historic Stonewall Inn — but the prison is much less known than its iconic neighbor.

In his newly released book, “The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison,” Ryan argues that the history of the “House of D,” as it was commonly called, is inextricably linked to the history of LGBTQ people in the U.S. — and vital when it comes to understanding the rights, identities and criminalization of queer Americans.

“I started with the simplest idea: that the Women’s House of Detention mattered. And it wasn’t even my idea. I was just listening to Joan Nestle, to Audre Lorde, to Jay Toole — to the queer elders who came before me, pointed to the prison and said, ‘There, there! We were there,’” Ryan writes in his latest book, released Tuesday.

Hundreds of thousands of women passed through the prison doors of the House of D, from suspected communists to alleged terrorists and even a would-be presidential assassin. Well-known figures incarcerated at the prison included the activist and scholar Angela Davis, feminist writer Andrea Dworkin and activist Afeni Shakur, Tupac’s mother.

Over the years, Ryan writes, inmates would describe the House of D as “a snake pit and hell hole,” and it would become known as the “Skyscraper Alcatraz” and “the shame of the city.” Throughout the decades, queer women were arrested for things like homelessness, smoking and forgery, but also for wearing pants, sending the word “lesbian” through the mail, being “incorrigible” and for being out at night alone.

For the long-gone prison to emerge on the page, Ryan brought together oral histories and public records, as well as documents left behind by social workers and prison administrators. In some cases, he was able to find people who had been incarcerated there or earlier accounts written by former inmates. The result is a vivid account of LGBTQ people imprisoned over several decades, many of them queer working-class New Yorkers, women of color and transmasculine people, all individuals whose stories have been underrepresented in historical narratives — and whose identities made them targets.

“One of the things I often say is there are two ways we end up in the record,” Ryan told NBC News. “We either have power, in which case we can preserve our own stories … or other people have power over us, and we get into the archive as the raw material of their research, or their practices, or their attempts to contain, control and understand us.”

'A defiant pocket of female resistance'

The House of D was central to Greenwich Village, and it became the place women were taken when they were arrested in the nearby mafia-run gay bars, or when they were caught in defiance of the “three-article rule,” which required women to wear three pieces of female attire to avoid being arrested for cross-dressing. A place of overcrowding, atrocious punishments and vast abuses of power, the prison was also a place where queer identity was discovered and defined.

“The House of D helped make Greenwich Village queer, and the Village, in return, helped define queerness for America,” Ryan writes in his book.

The prison, he elaborated in an interview, “changed the understanding of sexuality and gender for the working class.”

“We often have this idea that the more marginalized the history, or the group that we’re writing the history of, the less effect it has on the world, the more separated it is. The House of D, given its central location, shows the ways in which that is not true,” he said, adding that the prison’s inmates “were changing the world through what they were doing inside the prison.”

By imprisoning so many LGBTQ people, Ryan said, a queer community was inadvertently created.

“They’re teaching these people the same language for [homosexuality], the same understanding of what it is,” he explained. “The courts, in their own way, were doing that for women and transmasculine people in the decades before and after World War II.”

Ryan writes about butch Brooklyn teenager Charlotte B., who first heard the word “homosexual” in the 1930s when a judge considered sending her to an institution because of it. Charlotte was accused of influencing girls to hitchhike with her — and maybe even seducing them. Charlotte said it wasn’t her fault the girls admired her as they would “a good-looking football hero.”

Charlotte was incarcerated at the House of D and fell in love with another inmate, a young woman named Virginia, and the two began seeing each other. Two-and-a-half years later, when they were both out of prison and things turned more serious, Charlotte had a breakdown about her feelings. Ryan writes, “In just a few short years, the criminal legal system had transformed Charlotte’s understanding of other women’s attractions to her. She no longer saw herself as a dazzling football hero but as a sexually broken person.”

Charlotte spent the next six weeks in “a period of extreme emotional stress,” according to case notes. She ran away to Florida and worked as a chauffeur. But she couldn’t deny her feelings. “I guess I tried to push something aside that can’t be pushed aside,” she wrote to her social worker, adding that “there is nothing in the world that I want more than Virginia,” and revealed they were back together.

The expression of queer relationships and desire was discussed, seen and heard both inside and around the House of D, creating early visibility even as outside forces attempted to squash its expression.

It was common to walk by the prison and see people shouting up to those behind the barred windows. Lovers and friends “discussed the availability of lawyers, the length of stay, family, conditions and the undying quality of true love,” wrote the lesbian writer Audre Lorde, who described her experience of Greenwich Village life in the late 1950s and early 1960s in her memoir “Zami: A New Spelling of My Name.” Lorde wrote that the prison “always felt like one up for our side — a defiant pocket of female resistance, ever-present as a reminder of possibility, as well as punishment.”

The defiance and female resistance Lorde describes was as much a part of the House of D’s history as the punishment and containment behind its walls. But not everyone came to the prison unsure about who they were.

Ryan tells the story of Renée S., a Black teen who was incarcerated at the House of D in 1949 and had a relationship with a woman named Bernice. By all accounts, Renée and Bernice were incredibly self-assured and clear about who they were, even though who they were was a crime. Ryan writes that their pride “suggests that ideas of self-acceptance and queer liberation was percolating among the most marginalized even before they manifested in the well-heeled homophile organizing.”

Homophile organizing began in the 1950s by gay activists who wanted to deemphasize the sexual aspect of their identity. These groups were instrumental in creating an organized movement that would later enable LGBTQ people to fight for rights on a broad scale.

Protests, riots and unrest occurred within the walls of the House of D as much as it occurred outside of them. Riots in the 1950s exposed the prison’s flaws to the public, generating investigations and spurring the process of its eventual demolition. During the Stonewall Uprising of 1969, a mere 500 feet separated the prison and the bar. While rioting happened outside, inmates rioted inside, according to Ryan, burning mattresses, throwing lit items out the windows and screaming, “Gay rights, gay rights, gay rights!” What is often referred to as the modern gay rights movement had begun. The House of D would close two years later.

'Broken systems' and 'disappeared' lives

Ryan’s journey into the House of D asks the reader to consider not only the queer history of the prison, but the broader system of incarceration and its subjugation of LGBTQ people.

Though America’s incarceration rate has been falling, with 2 million people behind bars, the U.S. has more prisoners than any other country in the world, according to a 2021 Pew Research Center report. LGBTQ people are overrepresented at every stage of incarceration and are more than three times as likely to be imprisoned.

Ryan said that in doing this research he found that the prison system is “not a broken system, but every other system around it is broken.”

“Our housing system, our mental health system, our health system, our education system, our welfare system, all of those broken systems create people in need of care, which we don’t provide,” he said. “Instead, we use prisons as a method of social control…we have a women’s legal system that is about punishing women who do not act as wives, maids or mothers.”

The House of D was demolished nearly a half-century ago, and there is now a park where it once stood. Ryan describes it as “one of the loveliest places I can’t stand.” The neighborhood remains central to the LGBTQ community, but it’s also a place of multimillion-dollar townhouses, high-end boutiques and unaffordable rent.

There are no more friends and lovers calling up to those behind bars, and there are no passersby to witness it. Today, a disproportionate share of prisons and inmates are located in rural areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Prisons like the House of D, existing among people’s homes and jobs, are rare.

Joan Nestle, an activist who founded the Lesbian Herstory Archives in 1973, said that’s by design.

“When the Women’s House of Detention was torn down, it was done as an act, I would say, of the elite classes to rid themselves of the shameful public image of women calling out their love,” she said on a recent panel about the House of D where Ryan also appeared. “They disappeared the history. They disappeared these women’s lives.”

“I’ll ask you,” Nestle continued, “How many of you have walked by a women’s prison in your lifetime?”