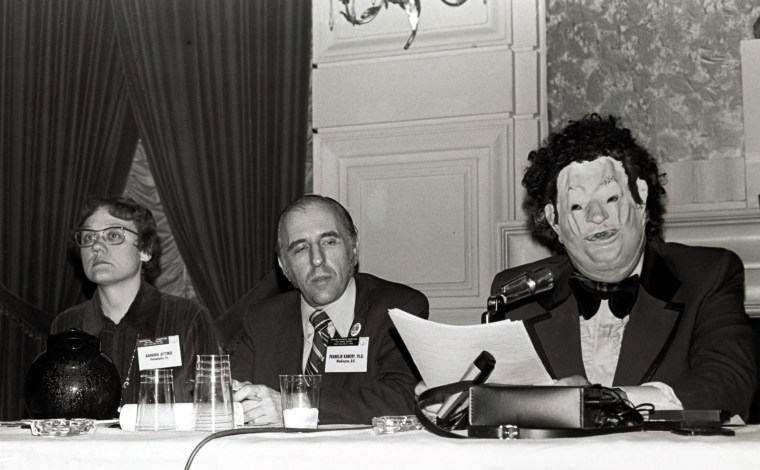

They thought he’d wear a mask that was a little more subtle. Something like the Lone Ranger, just a piece of cloth around the eyes. But no.

Introduced to the room as Dr. Henry Anonymous, wearing a wig and a tuxedo three sizes too big, and speaking through a microphone that distorted his voice, Dr. John Fryer stood in front of a crowd of psychiatrists at their annual meeting donning a garish Richard M. Nixon mask he and his lover had modified.

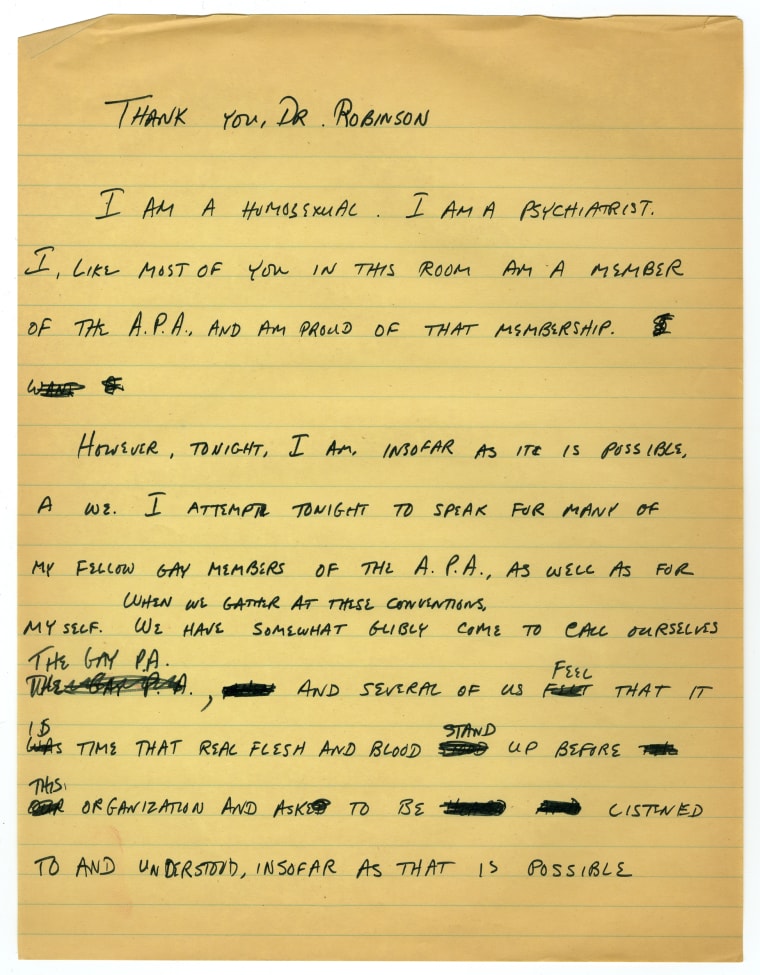

It was 1972, and he masked himself in order to say the following words: “I am a homosexual. I am a psychiatrist.” His declaration changed the world.

It has been 50 years since Fryer’s speech, a moment that was central to removing homosexuality from the list of mental disorders, the impact of which contributed to the progression of LGBTQ rights through the next several decades.

“From my viewpoint, Fryer’s testimony on May 2, 1972, is at least equal in significance to Stonewall. Both of them are hugely important moments in terms of LGBT civil rights,” said Malcolm Lazin, executive director of Equality Forum, an LGBTQ organization that has long supported the scholarship and recognition of Fryer’s work.

Removing the classification of homosexuality as a mental illness had been a mission of gay activists since at least the mid-1960s. Homosexuality was first classified as a disorder in 1952, when the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (commonly known as the DSM, the bible of the psychiatric field and the book from which all diagnoses are recognized) was published. The classification meant people could be institutionalized against their will, fired from their job, denied a mortgage or have their rights otherwise limited. Homosexual desire was considered an affliction, and acceptable “cures” included treatments like chemical castration, electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomy.

“As a class, we were mentally ill — no exceptions. And that was totally wrong to begin with. And their science was poor,” said Kay Tobin Lahusen, an early gay rights activist who helped to organize Fryer’s speech with her partner, Barbara Gittings, a pioneering lesbian who would come to be known as the mother of lesbian and gay liberation. Lahusen spoke to NBC News in 2019, two years before her death last year. Gittings died in 2007.

“I had been thrown out of a residency because I was gay; I had lost a job because I was gay. That perspective needed to be heard from a gay psychiatrist by an audience that perhaps might be more inclined to listen to a psychiatrist."

dR. JOHN FRYER

When activists began increasing pressure on the American Psychiatric Association, in the early 1970s (“Stop talking about us and start talking to us!” was the activists’ refrain), Fryer thought it was “a fool’s errand,” according to an interview with the public radio program and podcast ”This American Life” in 2002, a year before his death. He said he wished the activists would “shut up” and that he was embarrassed by them.

The association invited the activists to its annual meeting in 1972 as a concession to gay protesters who had stormed the conference in San Francisco in 1970 and Washington, D.C., in 1971. The 1972 panel, at the conference in Dallas, was called “Psychiatry: Friend or Foe to Homosexuals? A Dialogue.”

“They put on two psychiatrists, and they put on two gay people,” Lahusen said. The two gay people were Gittings and activist Frank Kameny. “But then I said to Barbara, ‘Well, it doesn’t seem right that we have two of the one, two of the the other, but we don’t have a psychiatrist who’s also gay.’ And I said, ‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful to have that reflected on the panel?’”

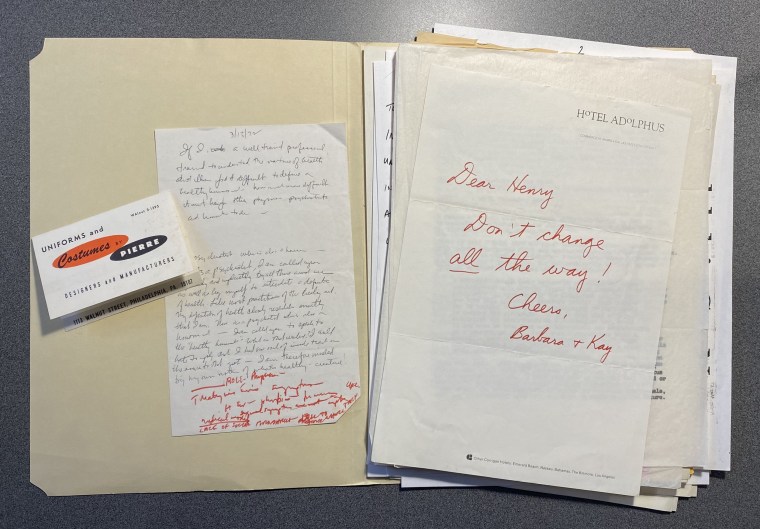

There was an underground group at the time called the Gay-P-A, which was made up of mostly gay psychiatrists who met in secret, at the same time as the association’s annual conference. Gittings and Lahusen wrote letters to everyone in the Gay-P-A they could reach and asked if they would speak.

“Well, they all wrote back saying no. They could not afford to come out. It would ruin their careers. They might lose their medical licenses. Their referrals would dry up. And they couldn’t possibly do that kind of thing,” Lahusen said. “Well, we thought it was hopeless, but we had one name left, and that was John Fryer.”

The pair called Fryer and told him he was their “last hope,” Lahusen recalled. But he, too, said no — at first.

Months later, Fryer, then a nontenured clinical faculty member at Philadelphia’s Temple University, contacted Lahusen and Gittings following a change of heart.

“I thought about it and realized it was something that had to be done,” Fryer recalled decades later, according to an article published in a 2002 issue of the “Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy.” “I had been thrown out of a residency because I was gay; I had lost a job because I was gay. That perspective needed to be heard from a gay psychiatrist by an audience that perhaps might be more inclined to listen to a psychiatrist.”

But he couldn’t do it as himself.

“He said, ‘Well, if I think about it, I could do it if I could wear a mask. And have a distorted microphone and wear a costume,” said Lahusen, who laughed as she recalled his “grotesque” Richard Nixon mask, “awful wig” and oversized suit. “And that’s how Dr. H. Anonymous came about.”

As Dr. Anonymous, Fryer’s speech at the APA conference sought to describe to the heterosexuals in the room the plight of their homosexual colleagues, who would have their “dooms sealed” should their “secret be known.” He also urged fellow gay psychiatrists to take a risk and “attempt to change the attitudes of both homosexuals and heterosexuals toward homosexuality.”

By remaining closeted, he told his fellow gay psychiatrists, “we are taking an even bigger risk … in not living fully our humanity, with all of the lessons it has to teach all the other humans around us.”

Fryer received a standing ovation. Notably, there was a man in the front row, a hospital administrator, who applauded the bravery of the masked man before him. A year later, that same administrator would fire Fryer for being gay, oblivious to the fact he’d applauded him as Dr. Anonymous. The man told Fryer, “If you were gay and not flamboyant we would keep you. If you were flamboyant and not gay we would keep you. But since you are both gay and flamboyant, we cannot keep you,” according to an account Fryer described in the Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy in 2002. (Fryer had lost a job because of his sexuality once before, in 1964, as a third-year resident at the University of Pennsylvania.)

Though Fryer wouldn’t come out as Dr. Anonymous to the APA for another 20 years, homosexuality as a mental disorder was removed from the DSM in 1973. When the change was made, the trustees of the APA stated the association “supports and urges the enactment of civil rights legislation at local, state, and federal levels that would insure homosexual citizens the same protections now guaranteed to others.” The removal of homosexuality from the DSM contributed to the fight for LGBTQ rights in myriad ways, especially because the diagnostic manual was not used only by psychiatrists — it was used by insurance companies, the U.S. government and other institutions.

“The removal of the diagnosis removed the rationalization for discrimination by churches, by the military, by schools. They can no longer hide behind medicine and psychiatry. Medicine and psychiatry took itself out of that discussion,” said Dr. Jack Drescher, a member of the Association of LGBTQ Psychiatrists and editor emeritus of the Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health.

Drescher said his career wouldn’t have been possible without the work of Fryer and the activists of that generation. He said that once homosexuality was removed from the manual, it was easier for more people to feel comfortable coming out.

“Once you have public conversations, you’re discussing what’s possible, you’re changing the rules of what is possible to talk about, and then more people start speaking up,” he said.

On Monday, a half century after Fryer’s history-making speech before fellow psychiatrists, the mayor of Philadelphia will honor the late doctor at an event celebrating his legacy. This follows the recent addition of his home to the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places and last week’s introduction of a resolution by two members of Congress to mark May 2 as Dr. John E. Fryer Day.

“Dr. Fryer’s courage as the first American psychiatrist to speak publicly about his homosexuality changed the course of LGBTQ history,” Rep. Dwight Evans, D-Pa., a co-sponsor of the resolution and member of the Congressional LGBTQ+ Equality Caucus, said in a statement, “With the APA’s classification reversed, states around the country began to repeal discriminatory ‘sodomy’ and anti-gay laws over the following years, clearing the way for millions of Americans to come out and live happier, healthier lives. This momentous change also helped activists and allies to push for the passage of local and state nondiscrimination laws.”

The American Psychiatric Association established an award in Fryer’s honor in 2005 — aptly called the John Fryer Award, which honors an individual who has contributed to improving the mental health of sexual minorities — and the Association of LGBTQ+ Psychiatrists includes Fryer’s work as an integral part of its history.

Fryer’s papers are stored at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Among a file of poems he wrote in the 1960s, there’s a portion of one that reads “When I leave/for good/will it be a church full/or just enough have gone before/and are left behind.” It is impossible to know exactly what Fryer meant by this, but at the time he wrote it, he would’ve been closeted and would not likely have believed how much psychiatry would change — or that he would be the one to play such a part in its evolution, or that he would change his own life and the lives of countless others.

When Fryer died in 2003 at 65, it was a metaphorical church full.