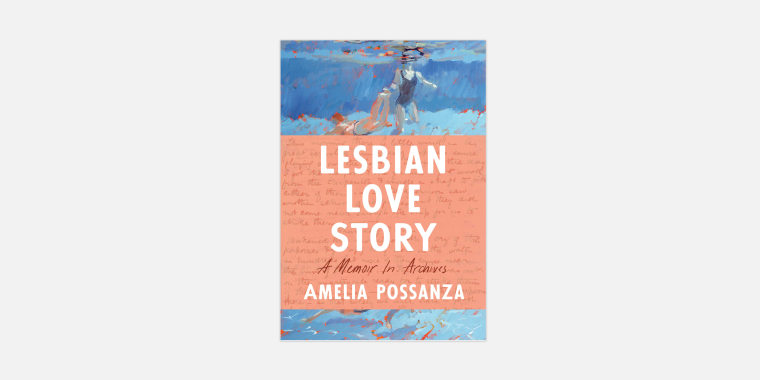

Writing her debut book, “Lesbian Love Story: A Memoir in Archives,” Amelia Possanza kept questioning why the stories of some people get a place in the history books, while others get lost to time. For her newly released history of sapphic romances, which span from the turn of the 20th century to the early 1990s, Possanza said she largely chose to focus on women who were brave enough to embrace what she described as a funny-sounding, slightly taboo L-word, which even her own mother still has trouble saying.

“I really wanted to focus on people who had lived an out life or chose to live a different sort of life than what they were prescribed at the time — people who used the word ‘lesbian,’” Possanza said.

“Lesbian Love Story” started as a kind of self-discovery mission for Possanza, a writer and book publishing professional, who said she has turned to books for answers throughout her life. In this case, Possanza went looking in historical works for self-described lesbians who could serve as role models for her own sapphic journey. And what she ended up finding, with a lot of digging, were inspiring everyday people whose lives were shaped by love stories. She tells these stories through a combination of nonfiction prose, selections from firsthand accounts and fan-fiction-like recreations of intimate moments.

It took years of research and combing through many different archives for her to find her subjects. Possanza said certain criteria ruled out some of the usual suspects, like Eleanor Roosevelt and Emily Dickinson, who never confirmed their much-speculated-upon queerness with words like “lesbian” and “sapphic.” So she had to scour accounts of cultural revolutions, wars and social movements for mentions of lesser-known lesbians, even if only as footnotes.

In the end, she unearthed seven notable figures, who are each at the center of a chapter in “Lesbian Love Story.” In mostly chronological order — interrupted by the Greek poet Sappho, in the middle — their stories and those of the women who loved them unfold. They are a turn-of-the-century memoirist and her muse, a Harlem Renaissance-era performer and her “wifey,” a midcentury golf legend and her protégé, the poetess of Lesbos and the woman who broke her heart, a Coney Island male impersonator and her stripper paramour, a duo of revolutionary ‘70s thinkers and a writer who cared for her friend as he died from AIDS.

The book’s first romance — between Mary Casal, a writer and entrepreneur from New England, and the woman she fell instantly in love with on a business trip to New York in 1892 — is its defining one. Possanza first came across Casal in a book about the 1969 Stonewall uprising, which mentioned in a “very offhand remark” that Casal’s memoir, “The Stone Wall,” was the namesake of the bar where the modern-day gay rights movement was born.

That causal remark sent Possanza on a mission to find the obscure memoir and learn about its long-forgotten author, known only by her pseudonym. When she finally located a copy of the book — which she said most likely isn’t the namesake of the iconic gay bar — what she found was a meet-cute for the ages and a starting place for her own literary debut: the turn of the 20th century, an era when opportunity and ignorance collided and the modern lesbian love story was born.

“You would grow up in your parents’ house, you’d get married, and you’d be sent off, and there wasn’t a lot of opportunity to socialize with large groups of women — and then, suddenly, [women] were at colleges, and there was the opportunity,” Possanza said of the late 19th century, when women’s colleges, like Wellesley and Vassar, proliferated and Casal came of age. “And that opportunity was not matched by a rising backlash — just yet.”

Related links:

Possanza said that unmarried women at the time would live together in “Boston marriages” and as “romantic friends” and that questions typically wouldn’t be asked.

“Middle-class white women kind of got away with it for a long time,” she said.

Possanza said that by the later part of Casal’s life, in the 1920s and ‘30s — when the book’s subsequent love story, between Mabel Hampton and Lillian Foster, began — the general public had significantly wised up. And that caused lawmakers and police to crack down on elements of society deemed undesirable, using so-called obscenity laws to justify targeting queer people.

At the same time, there was a kind of fervor for content about homosexuality, leading to the popularity of amateur sexology titles that, as Possanza writes in the book, “stepped in to satiate the curiosity of both a clinical and a general audience.” As a result, Casal was commissioned to write her memoir, “The Stone Wall,” which her publishers, in correspondence with each other, referred to as “the ‘Lesbian’ manuscript.”

Leaving the era of obscenity laws and amateur sexology behind, Possanza charts the evolution of lesbian life up until the 1990s, taking a detour midway to visit ancient Greece and the island of Lesbos — home to the poet who became known throughout history for her sensual depiction of female lovers. And, in the process, the self-described “nerdy words person” explores how the term “lesbian” evolved in tandem with the ways people who used the word could express themselves, both publicly and privately.

“I realized that the word has not always meant the same thing. It has not been a static category or a static identity group,” Possanza said. “It expands to catch a lot of people in some eras, and then in other eras, like the ‘70s, it contracts to exclude a lot of people.”

Given Possanza’s criteria for who gets to be a lesbian, her subjects look different from what one might expect by today’s standards. A few of them, like Casal and golf pro Babe Didrikson, were married to men at some point in their lives. Others, like the feminist writer and theorist Gloria Anzaldúa, who rejected her contemporaries’ narrow definition of “lesbian,” had male lovers and embraced nonmonogamy. And a few, including Hampton and Rusty Brown, seemed to express a desire to live beyond the gender binary.

Even the author’s approach to what constitutes a lesbian love story defies expectations, expanding to include platonic and familial love. The book’s final chapter centers on the difficult but defining friendship between a lesbian journalist, Amy Hoffman, and her former co-worker Mike Riegle, whom she cared for as he died from AIDS. And much of Sappho’s chapter is dedicated to Possanza’s relationship with her father, a classics scholar whom she credits with her love of reading and words.

But perhaps that’s not surprising, since the author, a self-identified lesbian, said she’s not a lesbian “in the way most people expect.” And, as she relays in the sections of memoir woven into the book, she has spent much of her life feeling like an outsider in her community because of it.

When Didrikson — one of the most accomplished athletes in the world in the 1930s through the 1950s — has to feminize her look to find commercial success, Possanza recalls feeling out of place on swim teams, explicitly queer and otherwise, throughout her life. When Sappho takes lovers of various genders at will, Possanza contemplates her relationship with her high school boyfriend, while scrolling through the lesbian dating app Lex and posts seeking “full-blown” lesbians only. When Hampton meets and falls in love with Foster, whom she refers to as her “real wifey,” Possanza tries and fails to embrace nonmonogamy.

Possanza ends the book with one final story, which neatly sums up the point she lays out over nearly 250 painstakingly researched pages.

“After I had learned enough about lesbians to hold my own, I reached out to Joan Nestle for an interview,” Possanza writes in her epilogue, referring to the co-founder of New York City’s Lesbian Herstory Archives, who figures prominently in Hampton’s chapter.

“‘The archives was created to break the concept of fame,’ she told me. ‘If you have the courage to touch another woman and to claim that touch … that, for us, was fame enough.’”