Around 6 o’clock on a cool summer morning in Calais, Maine, Greg Bridges drove past his fields of wild blueberries, debating whether to give up on his family farm.

Occasionally, he would park his truck and kneel in the dew to check his crop. About 30,000 pounds of wild blueberries were quickly ripening despite a very wet summer.

Bridges didn’t yet know the 2019 price of wild blueberries, but he guessed it wouldn’t be good. Exports to China had nearly vanished in President Donald Trump’s trade war, making an already precarious existence more difficult.

He had hoped wild blueberry growers would qualify for the administration’s subsidies for farmers who had been hurt by the trade war. But a week earlier, he learned the U.S. Department of Agriculture had declined the industry’s request. That summer morning, Bridges — a third-generation farmer, and a former marketing chairman for the Wild Blueberry Association of North America — drove back to his house and told his family he was giving up.

“You have to read the writing on the wall,” Bridges said. “It’s very disheartening when you put your heart and soul into something that’s basically ruined because of trade politics.”

In Maine, where blueberries have been an important export since before the Civil War, the trade war has squeezed the juice out of an iconic state industry. First, the trade war cost wild berry farmers a growing market in China, as China imposed gradually increasing tariffs on frozen fruit in response to U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods. Then none of the Trump administration’s trade-war bailout money reached Maine farmers.

A thousand miles west, meanwhile, a different berry has had much better luck. In Eagle River, Wisconsin, Dave Nokomis has just finished harvesting his cranberries. As usual, he flooded his marshes with water to create a bumpy sea of floating berries.

In August, Lake Nokomis Cranberries received a direct payment of $125,000 from the USDA. The farm will likely get another $125,000 in the next two months. It’s enough for Nokomis to weather the damage the trade war has done to cranberry sales in China.

“As soon as we heard even the faintest thing about it,” Nokomis said, “we applied immediately.”

The U.S. trade war with China has devastated many farmers and ranchers who were crucial to Trump’s election. Last July, Trump asked Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue to craft a short-term solution — a bailout for affected farmers. The program, now in its second year, is on track to pay $24.5 billion directly into farmers’ hands by January. After that, the program will be out of money and need a third round of funding to continue in 2020.

But not all crops are created equal. Wild blueberry farmers didn’t make the list for direct subsidies, even after Maine’s state government and entire congressional representation went to bat for them. Instead, wild blueberry farmers are eligible for money from a much smaller program that purchases surplus commodities — but all of last year’s funds went to a single, Canadian-owned company operating in Maine.

A USDA official told NBC News there wasn’t a “specific” or “exact formula” for determining which crops win the lottery and which don’t. Experts contend the USDA’s process has not been transparent.

“We're all basically guessing as to why certain crops were included and others weren't,” said Veronica Nigh, an economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation.

“There’s no transparency and no accountability,” said Joshua Sewell, senior policy analyst at Taxpayers for Common Sense, a bipartisan D.C. budget watchdog group. “When you look at the trade war aid, you’ve essentially produced a shadow farm bill with no debate and no Congressional input. It was just the Secretary of Agriculture deciding how to do it.”

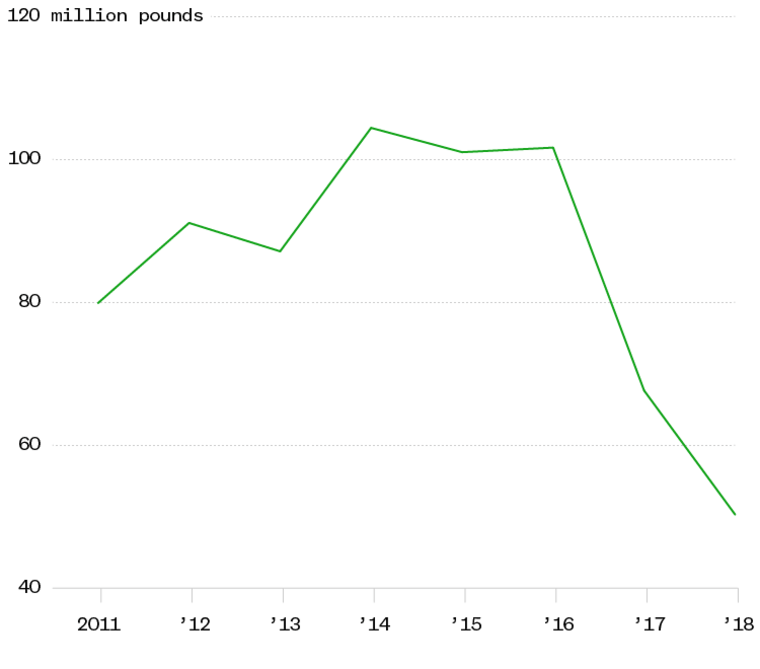

This November, Maine’s ruby-red blueberry barrens are freckled with rotting fruit, which should have been picked months ago. Because of bad weather, falling domestic prices and the trade war, more and more farmers like Greg Bridges are giving up. Since 2016, nearly 1 in 5 wild blueberry acres has gone unharvested. The harvest has fallen by half — from 102 million pounds to 50 million pounds.

“We just keep losing everything,” said farmer Leon Perry. “Wild blueberries were everything to us.”

‘Wild blueberries are better’

Maine is the only state that produces wild blueberries commercially, thanks to its highly acidic soil. Proud Mainers say regular blueberries just can’t compare.

“All blueberries are good, but wild blueberries are better,” Shannon Lion, who has harvested wild blueberries for 45 years, said.

A regular blueberry is big and blue with a gray-green interior. A wild blueberry is more like a tiny red plum, with deep magenta juices. They are highly perishable and almost always sold frozen.

One of the few fruits native to North America, wild blueberries have never been planted — just nurtured where found. A single plant can be centuries old and extend the length of a football field, uniting hundreds of bushes via an underground stem network.

The wild blueberry plant is tenacious. But the wild blueberry industry, much like the fruit itself, is small and fragile.

Overproduction began driving the price of berries down, with total crop valuation falling from $63 million to $18 million between 2014 and 2017. Canada started producing more wild blueberries than ever. And now regular blueberries are moving into the frozen foods aisle — wild blueberry turf.

U.S. wild blueberry production

All these factors convinced the U.S. wild blueberry industry to look to China for help.

“Our reasoning was everyone’s reasoning: Here are 1.3 billion people in a market that just continues to open up,” said Patricia Kontur, export program director at the Old Town, Maine-based U.S. Wild Blueberry Association of North America.

Kontur says she took dozens of trips to China in recent years, organizing trade shows, education initiatives and chef trainings featuring recipes like “Szechuan Crispy Duck with Chinese Wild Blueberry Sauce.” Over half of her export budget targeted Chinese consumers, she said.

It was working. The American crop caught on in China — marketed as a luxury superfruit, good for the brain and good for eyesight, said Dr. Dave Creech, a horticulturist at Stephen F. Austin State University in Texas.

Creech even attended an international blueberry beauty pageant in Yichun, China, where thousands of Chinese spectators applauded events like the “blueberry bikini contest” and the “eating blueberries elegantly” contest, staged in front of a gigantic wild blueberry sculpture.

Exports to China quadrupled in three years — jumping from 1 percent to 7 percent of total U.S. wild blueberry exports by 2017. Leaders say they were expecting the floodgates to open in 2018. Instead, the industry found itself caught in the crossfire of the U.S.-China trade war.

“We had made a major investment in the market and then the market more or less crashed,” Kontur said. “Businesses go out of business when it crashes like that.”

China first imposed tariffs on frozen fruit in April 2018 in response to the first big round of Trump administration tariffs on Chinese imports. China increased the tariffs in June and September 2019, each time after hikes in U.S. tariffs.

Today, frozen wild blueberries face an 80 percent tariff in China. Exports have plummeted from $2.5 million in 2017 to just $61,000 this year as of September.

A tale of two berries

In summer 2018, the Trump administration announced which crops were eligible for the USDA's initial trade-war bailout payments. Blueberries, whether regular or wild, were not included. Neither were cranberries.

Both berries benefited from a smaller, lesser-known pot of money, the $1.2 billion Food Purchase and Distribution program, which purchases commodities for food banks. Farmers don’t seem to have much faith in what they see as the USDA’s consolation prize.

For blueberry farmers, the program got off on the wrong foot last year, when Cherryfield Foods emerged as the only recipient of the funds. Its parent company is Canada’s Oxford Frozen Foods, the world’s largest frozen wild blueberry supplier. Cherryfield and an affiliated land-holding company reported nearly 50,000 acres in Maine to USDA as foreign-owned land, according to foreign investment disclosure records obtained by NBC News.

“We’re all in line — our goals, our objectives, our companies,” said Jordan Burkhardt, director of administration at Oxford Frozen Foods. “Our operations are not kept separate.”

American farmers worry the bailout to protect them may have actually funded Canadian wild blueberries, who many see as their biggest international competitor.

“That money is a down payment on a Canadian freezer,” said Courtney Hammond, a wild blueberry farmer. “Not one penny will trickle down to the American farmer.”

When the USDA reauthorized its major bailout program for 2019, both cranberries and wild blueberries wanted in on the $14.5 billion direct payments.

The bailout program’s beneficiaries expanded from nine listed commodities to 39. Cranberries got added. Both wild and regular blueberries did not, even after Maine’s Department of Agriculture and congressional representatives both sent letters to the administration.

“It would have been helpful to see why we didn’t qualify,” Nancy McBrady, a bureau director at Maine’s Department of Agriculture, said. “USDA was also ignoring the fact that cranberries, which got direct payments this year, also had benefited from the food purchase program. Why are wild blueberries dinged for that and cranberries are not?”

It’s a common question from the industry; farmers appear particularly miffed that wild blueberries were outflanked by cranberries. It’s not personal, they say. The petite, colorful fruits just have a lot in common. Both are native, perennial, geographically concentrated crops, oversupplied and increasingly reliant on China.

But the annual value of cranberry production is 10 to 15 times that of the wild blueberry crop. And unlike wild blueberries, cranberries have a well-funded, well-organized presence in Washington. There is a bipartisan Congressional Cranberry Caucus and an Ocean Spray PAC. Ocean Spray Cranberries spends $400,000 annually on lobbying. It hired K Street veterans Cassidy & Associates this year for, among other things, lobbying on “retaliatory tariffs on cranberry products.”

The Cranberry Marketing Committee, a federal marketing group housed under the USDA, holds bi-annual meetings. Half are at the Ritz-Carlton, and all have tariffs on the agenda and a USDA representative present, according to meeting minutes available from 2017 onwards.

“The USDA offices that did the calculations are careful professionals, but somewhere these decisions are influenced by a political conversation,” Dan Sumner, director of the University of California Agricultural Issues Center, said. “This is not new to this administration. Commodity organizations come to Washington and say ‘if you want to make our growers the least unhappy, here’s how you do that. Unfortunately, that means an industry that isn’t actively organized in Washington gets passed over.”

Because the USDA controls the purse, some traditional lobbying strategies, like cultivating the local congressman’s office, are less effective.

“A lot of commodity groups have gone out and tried to retain consultants who have direct line to folks in the White House to meet directly with USDA and argue why their particular commodity is in need of additional funds,” said David Beaudreau, a senior vice president at D.C. Legislative and Regulatory Services, a lobbying firm specializing in agriculture.

Growers of state-specific commodities like blueberries may struggle to be heard by the federal executive branch — and suffer the financial consequences.

“Wild blueberry farmers are feeling the pinch as hard as soybean farmers, if not harder, because we have no hope for government assistance whatsoever,” said Bruce Hall, Wild Blueberry Advisory Committee chairperson and an agronomist for Wyman’s, a blueberry company in Millbridge, Maine. “We’re not the Iowa Soybean Association. The government is not really receptive to an industry as small as ours.”

U.S. wild blueberry exports to China

Steve Peterson, acting administrator of USDA's Farm Service Agency, said critics who question why some crops get more money than others may be frustrated by the lack of an “exact” or “specific formula.”

“Some may feel the information is not there,” said Peterson, but he emphasizes decisions about eligibility are “based on knowledge that specialist experts have within USDA, determining how those commodities can be utilized either domestically, how they’re impacted by the exports and whether tariffs are being applied.”

Peterson said USDA has a “wealth” of expert knowledge to make such decisions.

Asked why cranberries got money and wild blueberries did not, the USDA did not comment, other than to say the size of an industry is not a limiting factor. Otherwise, the USDA referred NBC News to previously published reports from 2018 and 2019 that do not address crop eligibility criteria.

Cranberry exports to China reached a record high in 2018. This year, they are on track for a roughly 30 percent loss. The USDA had paid nearly $4 million to 284 cranberry farms by early September, just six weeks into the 19-week sign-up window, according to payment data obtained by NBC News.

In Wisconsin, the USDA bailout funds are cushioning the impact on Dave Nokomis – for now.

“They have to get this trade thing figured out,” Nokomis said. “We’re raising food. Everybody eats. There shouldn’t be an issue.”

‘I will farm until the money is gone’

As Mainers mourn the loss of the Chinese market, Canada’s Oxford Frozen Foods is “working hard to open new markets in places like China,” according to a March press release. It may even be benefiting from the U.S. trade war bailouts while doing so.

The mood is glum in the blueberry barrens. The berries will be fine, because they are wild. Farmed or not, they will keep popping up on rocks and roadsides, forests and mountains, or wherever else the soil permits.

Maine’s farmers are not so firmly rooted.

“Nobody knows how bad the blueberry industry is,” farmer Leon Perry said. “It seems to surprise people when I say there is no blueberry industry anymore. We lost our future.”

Perry and his wife live in a mobile home in Addison, Maine, population 1,266. Twenty-five years ago, he said, they began pouring money into blueberries — land, equipment and an in-house processing plant.

“Our thought was to put everything into what we were doing,” Perry said. “We would be able to afford a house later. Now, at 57, I have no retirement. I’ve got to be really careful about what I do in the future, because I cannot afford to make any more mistakes.”

Still, Perry says he will “farm until the money is gone.” Addison is in Washington County, where 65 percent of the nation’s wild blueberries grow and 21 percent of residents live below the poverty line. In a county with just three stoplights, wild blueberries do not need farmers, but farmers need wild blueberries.

Perry spends November days in the driver’s seat of an orange excavator, leveling his fields while listening to books on tape — recently lots of John Grisham. Then, he spreads the blueberry sod “like pizza dough in a pan.” Hopefully, by May 2021, the fields will be covered with white bell-shaped blueberry flowers.

Perry doesn’t hope for government help anymore, he says — just more sunshine.