Michael Kwan was 7 years old when his grandparents showed him a large steel safe in their Los Angeles home. In dramatic fashion, they opened it and pulled out a piece of paper.

“This belonged to my grandfather,” Kwan recalled his grandmother telling him. “He worked on the railroad.”

The document was a stock certificate from the Central Pacific Railroad, the company that built the western portion of the first transcontinental railroad by employing more than 10,000 Chinese laborers.

May 10 will mark the 150th anniversary of the railroad’s completion, an engineering marvel that linked the nation. Among its successes, it reduced cross-country travel time for passengers from months to about a week. The railroad also allowed goods to move more quickly and cheaply from coast to coast, as a fractured America and its economy recovered from the Civil War.

Kwan, 56, a criminal court judge in Utah, knows little about his great-great-grandfather. His name remains a mystery to him, as many names recorded by English speakers at the time were not accurate.

But he does know that he was recruited from the Kaiping area of China’s southern Guangdong province, a region embroiled in social turmoil at the time. He made passage to San Francisco by way of steamship, just like many other Chinese railroad laborers, and arrived without knowing English.

From there, he was brought to Sacramento — the city where the Central Pacific broke ground in 1863 — and sent to the end of the line.

That was where his job began.

“He worked very hard, it was very dangerous,” Kwan remembered his grandmother explaining. “People died, people that he knew died.”

BLASTING A LEDGE

Death was always a real possibility for the workers who built the railroad.

The Central Pacific, whose labor force by 1867 was almost 90 percent Chinese, faced an onslaught of tough terrain challenges as it moved east. That included tunneling and blasting through the imposing Sierra Nevada as part of the 690 total miles of track they put down.

By contrast, the Union Pacific, which worked west from Council Bluffs, Iowa (near Omaha), built its 1,086 mile-segment largely across the flat Midwestern prairies, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University.

For the first transcontinental railroad, the Union Pacific did not employ Chinese, Stanford researchers say, but instead relied on Civil War veterans and East Coast immigrants, among others.

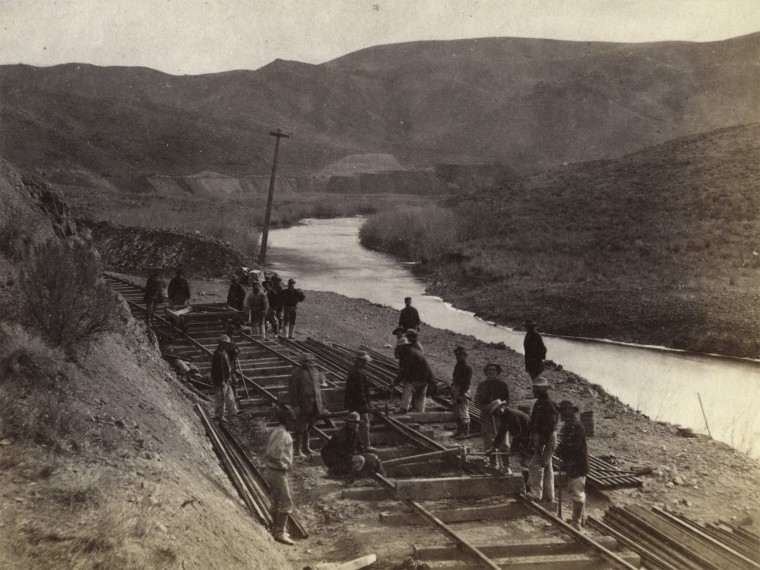

In the summer of 1865, the Chinese were put to the test in the Sierra Nevada, having been called upon to build a three-mile curved roadbed along a spot named Cape Horn. Toiling for about a year, they blasted out a ledge roughly 1,200 feet above the American River east of Colfax, California.

He worked very hard, it was very dangerous...People died, people that he knew died.

How this was accomplished is not without controversy, according to “Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad,” a forthcoming book written by Gordon H. Chang, a Stanford history professor and co-director of the Chinese Railroad Workers Project.

Many reports describe the Chinese lowering themselves in woven baskets, placing explosives to blast out rock they couldn’t chip away by hand. Those who didn’t ascend fast enough after lighting the fuse would die.

But others have dismissed those accounts as myths, saying that a Southern Pacific Railroad public relations agent concocted the story in 1927 to entertain travelers as they went around Cape Horn, Chang writes.

Chang asserts that firm evidence exists in overlooked accounts before 1927 of the Chinese using rope, chairs and baskets during their work in the Sierra Nevada.

“Whether these instances took place at Cape Horn or at other nearby locations is not clear, but the ‘baskets story’ is now more compelling than ever,” he notes.

TUNNELING THROUGH GRANITE

In the fall of 1865, the Chinese faced their most arduous challenge yet: digging 15 tunnels through the Sierra Nevada.

The sixth, called Summit Tunnel, proved the most difficult.

Crews were tasked with boring through solid granite nearly a third of a mile in length, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers Project. Many kegs of black powder were used daily for blasting, but the hard rock continually slowed their progress. A chemist on site even mixed nitroglycerin, a powerful new explosive deployed by the railroad for a short time.

To speed things up, company engineers ordered workers to dig out a vertical shaft from the top of the mountain that ran down to the halfway point of the tunnel, more than 72 feet deep, Chang writes in “Ghosts of Gold Mountain.”

As the Chinese worked at the tunnel’s east and west ends, other laborers were lowered down the shaft, allowing them to dig from the inside out. Buckets of debris, meanwhile, were lifted out of the mountain using the horsepower of an old steam engine.

At one point, to further quicken the pace, Cornish miners working in the Nevada silver mines were brought in for a competition with the Chinese, to see who could cut away rock the fastest, according to the project.

While the miners, from Cornwall in southwest England, had earned a reputation for being among the best in the world, the Chinese always ended up chipping away more rock each week.

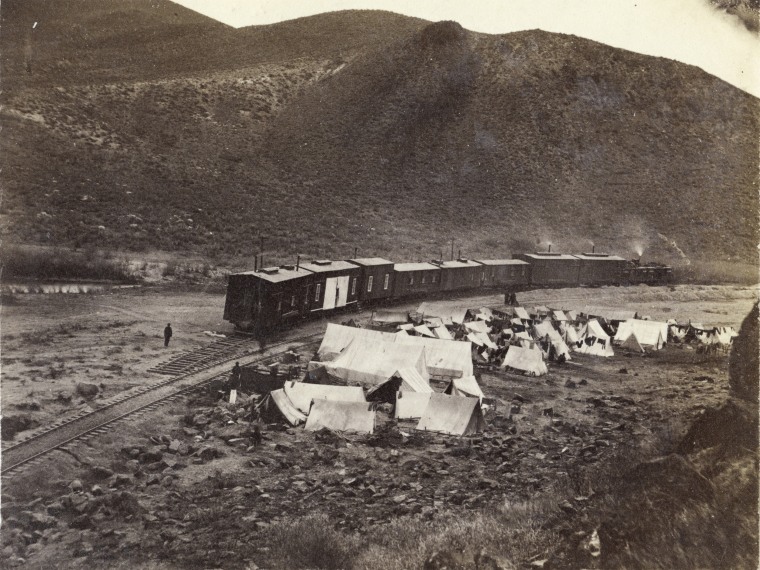

Constructed during two of the harshest winters on record, with avalanches and snow slides contributing to worker deaths, Summit Tunnel was finally completed in November 1867 — though not before the Chinese went on strike for eight days in June of that year.

“Up until that time, I think it must have been perhaps the largest, arguably the largest, labor action in American history,” Chang said.

Demanding shorter workdays, better treatment and equal pay to whites, several thousand Chinese in the Sierra Nevada laid down their tools and walked off the job, returning to their camps along the line. The strike ended after the Central Pacific cut off all their food and supplies, which forced the Chinese back to work.

Stanford scholars say the job action nonetheless helped counter the image that the Chinese were docile and wouldn’t fight for their rights.

“There were incidents of Chinese labor action before the strike, before 1867, and then afterwards,” Chang said. “So the idea that they were somehow tractable and manipulatable is misplaced.”

AN AMERICAN DREAM

As many as 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese were working on the railroad at any one time, according to the Chinese Railroad Workers Project. But most of them likely did not stay for the entire period of construction, owing to the difficulty and dangers of the work. Some found employment elsewhere; others chased after their own dreams.

Kwan’s great-great-grandfather was one of those men.

“He came here pretty much with nothing, and was able to work and save money, send some home, but saved enough to start a business, and then have a family of his own here,” Kwan explained.

That business, he said, was a grocery store in Stockton, California, around 50 miles south of Sacramento. It stayed in the family for two and a half generations.

Kwan, who serves as president of the Chinese Railroad Workers Descendants Association, said his family is currently doing genealogy work to learn more about his great-great-grandfather. But after getting as far as his grandmother’s mother, their efforts hit a brick wall because of poor record-keeping in America.

They’re hoping China might have records that could shed light on his ancestor’s life, one that Kwan said was emblematic of the American dream.

“Those stories don’t happen much in the world,” Kwan said. “They’re pretty unique to America.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.

More from NBC Asian America's series on the Chinese railroad workers: