While some students are recovering from a long holiday hiatus, Wesleyan University's Alton Wang is busy drafting a syllabus for an upcoming student-led course, “History, Gender and Sexuality Through the Lens of Asian American Voices.”

Last semester, Wang and fellow student Jenne He brainstormed ideas for a course highlighting the representation of Asian Americans in pop culture and history through various mediums. After hours of research, planning, and finessing, the course was approved by the university for the spring semester.

“Our curriculum is severely lacking," said Wang, who is currently a junior. "Only a couple courses exist that explicitly deal with Asian Americans, and they are both literature courses."

Wang has been at the forefront of the lobbying effort to include more ethnic studies and Asian-American courses at Wesleyan. They're needed, he says, to help students better explore the stories of historically marginalized and underrepresented communities.

“We are hoping, as of now, not for an entire major course of study," said Wang, "but simply more courses surrounding Asian Americans on campus."

Student-led courses or forums help enhance the university experience by handing over the textbooks and classroom to students. For Wang, it’s an opportunity to enhance the dialogue with the AAPI (Asian American Pacific Islander) community on campus.

“Your interests are similar, you eat similar foods. There wasn’t anything negative about that, but there was a lot of homogeneity."

For the 20-year-old, approval for a co-created student forum course brings him one step closer to potentially creating a full-fledged Asian-American Studies program at Wesleyan. But there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done.

For now, Wang says, it’s important just to show that there’s a growing interest in this course of study.

Growing up in the ‘626’

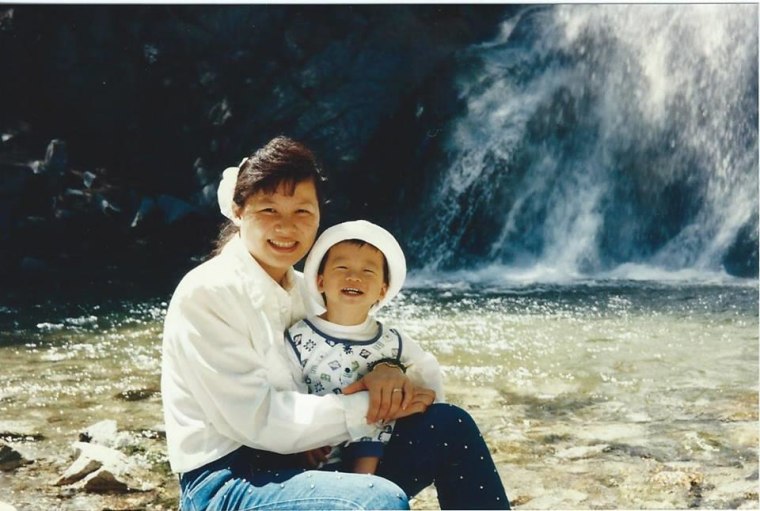

Wang, a first generation Taiwanese/Chinese American, grew up in Arcadia, Calif. – a city in the San Gabriel Valley predominantly populated by Asian Americans.

Wang’s parents immigrated to California from Taiwan in the early 1980's. Over the years, his parents juggled various jobs - everything from selling construction tools, to serving as insurance, loan, and real estate agents.

“Growing up in a place like the San Gabriel Valley, it can get very comfortable because you’re surrounded by people who are literally and culturally like you," said Wang. “Your interests are similar, you eat similar foods. There wasn’t anything negative about that, but there was a lot of homogeneity."

The San Gabriel Valley, commonly referred to by its area code - the “626” - is also the birthplace of the popular 626 Night Market, the largest Asian-American night market in the U.S., inspired by night markets in Asia. Since opening in 2012, it's attracted crowds of locals by offering an abundance of ethnic food, art, and retail booths, and tapping into local talents like comedy and music duo, the Fung Brothers.

"I wish that when I was growing up, I could’ve seen someone that had my skin color on the screen that I could actually look up to."

At Arcadia High, Wang's former high school, Asian Americans comprised 69 percent of the student body, and minorities comprised nearly 84 percent of the total population - a stark difference from Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

Growing up in the Valley, Wang says, there were moments when he felt somewhat alienated and isolated from the mainstream American media and culture he grew up trying to understand. He didn't see himself represented on the screen or in popular songs. Wang says he felt most comfortable listening to C-Pop (Chinese pop music) or watching Taiwanese television shows. He felt a connection to his culture and his roots.

Wang has blogged about the problem of media representation over the years for the AAPI community. In one post, "Searching for Yellow on the Screen," he wrote about his frustration.

"Media representation is important, to me, because it means that all children can grow up with their own heroes or role models that look like them." Wang wrote. "It is important because I wish that when I was growing up, I could’ve seen someone that had my skin color on the screen that I could actually look up to."

Recent strides in the entertainment industry - casting Asian Americans in lead roles and expanding their visibility - give Wang hope, but the story of the show "Selfie" - a popular network sitcom with John Cho in the lead, cancelled after six episodes - was a reminder that the opportunities for AAPIs on television are often short-lived.

“Why don’t these opportunities for Asian Americans on TV last?" Wang wondered. "I think it’s important because for me, I felt alienated as a kid from this culture I grew up in. Not everyone felt that way. But I couldn’t see myself in the American culture.”

In the San Gabriel Valley, Wang recalls, there was always an understanding that Asian Americans and their voices mattered. But in Connecticut, the dynamic was different. There was student activism, but little visibility.

“I wanted to leave Arcadia not because I didn’t love my hometown, but mostly because I wanted to go to an environment that was a complete 180-degree of what it was like growing up here," said Wang.

He wanted, Wang says, to make an impact in a place where minorities were not the majority.

Creating a new community at college

After moving to Connecticut, Wang became increasingly interested in AAPI civil rights issues as a government and sociology double major. Approximately 22 percent of his fellow first-year students were Asian American. He realized quickly, his voice carried less weight in this new balance.

“What brought me into the Asian-American world was going to Wesleyan and being exposed and thrust into race, social justice, inclusion, and diversity," said Wang. “I felt it was a hole in my college experience. I was so used to growing up with Asian Americans who faced similar experiences.”

During his junior year, he worked with friends and peers to create more visibility for the school's Asian-Americans, organizing campaigns and outreach efforts.

“how I can personally find a space where people think like me, that look like me, and come together and have a safe space to have a conversation"

He also became actively involved at the Asian American Student Collective, a student-led organization established in 2000 dedicated to enhancing and creating visibility for their community on campus.

“For me, it was thinking about how I can personally find a space where people think like me, that look like me, and come together and have a safe space to have a conversation,” said Wang, who currently serves as the chair of the organization.

Through the Collective, Wang brought Asian-American artist Awkwafina to campus, and launched a photo essay campaign entitled “So Where Are You Really From" - an in-depth look at the stereotypes that sometimes surround a first impression.

“The campaign was meant to spark dialogue about the issue of the ‘perpetual foreigner’ stereotype," said Wang, "where Asian Americans are constantly seen as individuals that do not belong in this country—that people automatically assume that we are foreigners.”

The Growing Interest in Ethnic Studies

Wesleyan does not currently offer an Asian American Studies program or major, though a few courses relating to Asian America do exist. On its website, the university lists a series of departments, programs, and centers dedicated to specific ethnic or racial fields of study, including African American Studies, American Studies, Center for Jewish Studies, College of East Asian Studies, South Asian Studies, Latin American Studies, Jewish and Israel Studies, and Middle Eastern Studies, among others.

Wang and his fellow members at the Student Collective continue to work to add Asian American studies to that list. Last semester, they arranged a meeting across different academic departments, student groups, and professors -- many of whom support the inclusion of more Asian-American course offerings on campus.

The university confirmed to NBC News that it has received a proposal from the American Studies department, spurred by Wang and the student body, to hire a visiting faculty member specializing in Asian-American history in order to further enhance the department’s already robust offerings.

“We also received a letter in support of this proposal, signed by more than 120 students. This request is currently under consideration,” a spokesperson told NBC News.

For his part, Wang says he won't give up the fight. He wants his fellow classmates, and the students who come after him to better understand the stories of racism and discrimination woven in the fabric of Asian-American history. These courses would help people better understand their roots in America, Wang says, to better understand who they are.

“We believe that it should be the right of every student to be able to not only see themselves in the curriculum," said Wang, "but learn their own histories."