Donald Trump’s immigration plan, entitled “Defend the Laws and Constitution of the United States,” calls for an end to “birthright citizenship.”

But legal and historical scholars say the GOP front-runner’s challenge attempts to trump the Constitution itself, as well as an important chapter in Asian American history.

Related: What Donald Trump's Immigration Plan Means

Birthright citizenship has been considered “settled law” since March 28, 1898, said John Trasvina, the Dean of the University of San Francisco Law School in an interview with NBC News.

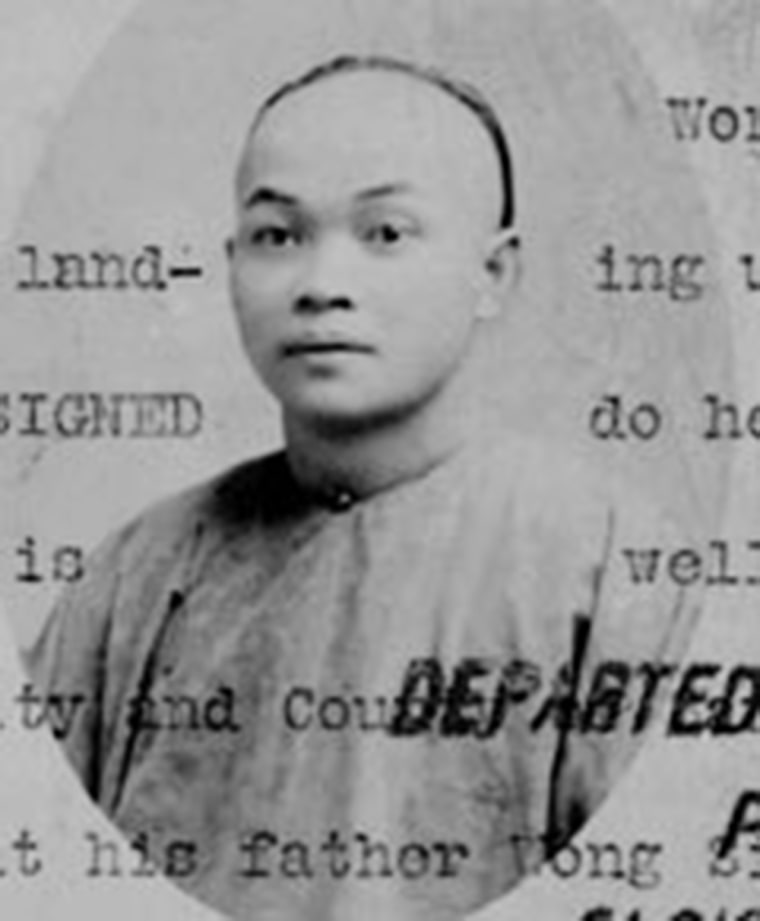

And it was all due to Wong Kim Ark, a Chinese American born in San Francisco in 1873.

In August of 1895, Wong was 22 and returning home to San Francisco after a visit to China, according to court records. But it was also an era when anti-Chinese sentiment was high, with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1886, and its renewal in 1892.

When Wong was refused re-entry to America, it set up his legal battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1898, the High Court affirmed Wong’s right that has continued to define citizenship birthright for 117 years.

“The U.S. Supreme Court noted that the nation's founders adopted Anglo American law which itself dated back to 1608 to interpret the meaning of the 14th Amendment -- if you are born here, you are a United States citizen,” said Trasvina.

He notes that the legal avenue to challenging and amending the Constitution would be "lengthy, divisive, and not likely to be successful."

“It would call into question the citizenship of millions of people born here, irrespective of the legal immigration status of the parents,” said Trasvina. “For that reason and because it is settled law and because courts tend not to narrow the scope of protection of the Constitution, it is unlikely that this would ever happen."

Related: Born in the USA: Film Explores Right to Citizenship at Birth

In a recent op-ed in the New York Daily News, Erika Lee - director of the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota - recalled Wong's role in establishing legal precedent on the issue, and outlined potential consequences of changing the law.

"Many immigration experts counter that ending birthright citizenship would create two tiers of unequal citizenship in the country and would be disastrous for the estimated 4.5 million people who have been born in the United States to undocumented immigrant parents," wrote Lee. "Such a change would further destroy families and disaffect another generation of immigrants and their U.S. citizen children."

Lee notes that despite his legal victory, that is precisely what happened to Wong, whose legal citizenship was never fully recognized by the U.S. government, and who was eventually forced to raise his family in China, where he died shortly after World War II.