A state Supreme Court decision not to extend Pennsylvania’s June 2 vote-by-mail deadline could depress turnout for many of the state’s more than 400,000 Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, advocates say.

Organizers with the Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition, a South Philadelphia-based nonprofit that was among the plaintiffs in the court case calling for an extension, said the extra time is needed so the thousands of low-income AAPI residents it serves can properly complete and return their mail-in ballots amid the coronavirus pandemic. Many of its constituents require assistance requesting and translating ballots — a task that has become more difficult and time-consuming as the crisis has halted in-person contact.

“We reach out to low-propensity, first-time voters in the AAPI community with limited English proficiency,” Thoai Nguyen, SEAMAAC’s chief executive, told NBC Asian America.

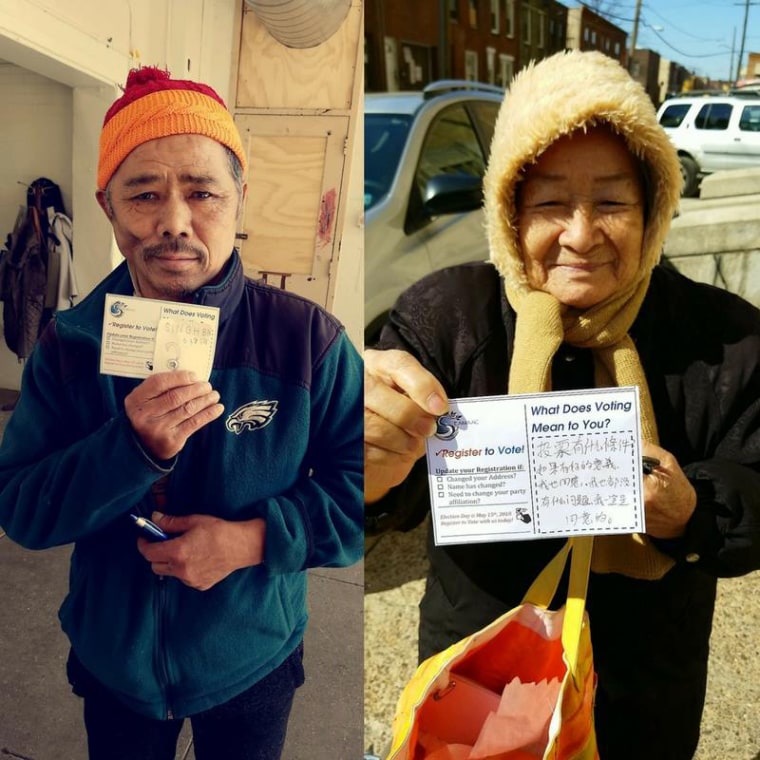

SEAMAAC, which conducts an extensive civic engagement campaign every election cycle, typically starts voter registration and get-out-the-vote activities two months before an election day, Nguyen said. Last year, it reached about 6,500 individual AAPI voters across the state mostly through door-to-door canvassing. But the group’s impact has diminished as operations moved online. Organizers are investing substantially more time and effort than before to remotely teach voters how to complete registration forms and ballot applications.

At the same time, the pandemic has caused postal service delays and triggered a tsunami of ballot requests statewide. (In Philadelphia, the tally is more than 20 times higher than in 2016.)

With the Pennsylvania primary a week and a half away, all these factors could contribute to a suppression of the AAPI vote — and alter the dynamics of a key swing state. In addition to the presidential primaries, voters will also cast ballots for 18 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In mid-April, the Public Interest Law Center, representing SEAMAAC and three other advocacy groups as well as voter Suzanne Erb, sought an preliminary injunction to have ballots be accepted so long as they’re postmarked by June 2 and received within a week. (Currently, the state requires that mail-in ballots be received by the day of voting.)

However, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court dismissed the challenge last Friday, arguing that asking voters to abide by the current deadline does not amount to a constitutional violation.

This setback will be felt acutely by the Asian electorate, who already face challenges at the polling station.

In recent decades, Asian Americans have become the fastest-growing electorate in the country, with more than11 million eligible voters. But the group’s turnout rate remains low due to barriers such as inadequate language access and minimal outreach from both parties.

In Pennsylvania, both the voter registration and ballot request forms are available only in English and Spanish. Normally, bilingual canvassers with SEAMAAC would show constituents how to fill out the forms in-person while translating in real time, which has become nearly impossible to do by text or phone.

In addition, many older constituents don’t have internet access at home, so they can’t request a ballot. (The deadline to request one is Tuesday, May 26.)

This is the first time Pennsylvania is allowing voters to apply for mail-in or absentee ballots without providing a reason. In past years, the option has been limited to people with disabilities or illness who physically couldn’t get to a polling station.

Implementing a new voting system would have been challenging even without the pandemic, especially in a presidential election when turnout is higher, said Ben Geffen, a staff attorney at the Public Interest Law Center, who noted that more than 600,000 mail-in ballot applications have been filed so far across the state.

“There’s a demonstrated concern that there will be a backlog of requests election officials won’t get to in time,” he said.

There’s still a glimmer of hope. The Pennsylvania Alliance for Retired Americans, a major Democratic political group, is awaiting judgment on a separate lawsuit seeking to extend the state’s mail-in ballot deadline, along with several other provisions to make by-mail voting easier.

But based on the current situation, anyone who hasn’t yet received a ballot faces a grim decision.

“If you get your ballot the day before the election,” Geffen said, “your only choices are to mail it and risk not having it arrive on time or take public transportation to the polling station, which isn’t consistent with social distancing.”

With the election approaching, SEAMAAC has hurried to register and mobilize as many voters as possible.

In addition to texting and phone-banking 15,000 people per week, staff and volunteers are putting informational flyers translated in various languages into hundreds of grocery boxes the organization distributes each day, said civic engagement coordinator Iris Bercovitz. The group has also hosted Zoom meetings with teachers and community leaders to spread the word about mail-in voting.

But the rush of new information has created a wave of confusion and wariness among constituents that’s not easily assuaged by phone.

“There’s this whole new obstacle around the psychology of vote-by-mail,” Bercovitz said. "People are wondering, 'How do I know my voice counts and matters? What happens if my ballot gets lost?'"

The chaotic mood of this primary cycle stands in stark contrast to the excitement of previous iterations, Nguyen said. In the past, the organization usually made election days into field trips, where staff would walk to voting centers with some of their constituents.

“A one-week extension shouldn't have been something we had to litigate over,” he said. “Our democratic system isn’t capable of adapting to a pandemic.”