Sothy Kum learned that he was being deported to Cambodia an hour before he boarded the bus that took him from an immigration detention center to an airport in El Paso, Texas, he said.

The 43-year-old didn’t have time to call his wife or change clothes beforehand, he added, and after more than 20 hours of travel, arrived in an unfamiliar country his family fled when he was about 2.

“Everything here is just totally the opposite in the U.S.,” Kum said. “The traffic, the way they ride their moped and go the wrong way. There's no stoplight.”

Kum was one of 43 Cambodian nationals who landed in the country on April 5 after being deported from the U.S.

Staff from the nonprofit Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC), which has been advocating for the individuals, said it was the largest group of people the organization has seen deported in a single day since a 2002 agreement between the U.S. and Cambodia.

“This recent group of removals … was very devastating to the community,” Katrina Dizon Mariategue, SEARAC's immigration policy manager, said. “We are very heartbroken for a lot of these family members, but we continue to stay hopeful."

Our entire family was extremely traumatized when they knocked on our door one morning and took him away from us.

The flight came about five months after civil rights advocates filed a lawsuit challenging the immigration detention of Cambodian nationals, many of whom came to the U.S. as refugees fleeing the Khmer Rouge. Late last year, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detained more than 100 Cambodian nationals with orders of removal, according to advocates.

A possible victory for some of the plaintiffs came Tuesday when the Supreme Court struck down part of a federal law that makes the deportation of immigrants convicted of certain crimes easier.

Christina So, strategic communications at Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Asian Law Caucus, one of the groups that filed the lawsuit, said the ruling will certainly be helpful for class members.

Phi Nguyen, litigation director at Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Atlanta, which, along with other groups filed a similar lawsuit on behalf of Vietnamese nationals, said that if an individual received their deportation order based on one of the crimes covered in the case, they have the ability to revisit and re-open their removal order.

Both So and Nguyen said their organizations still need to more closely examine the specific cases.

As of December 2017, there were more than 1,900 Cambodian nationals with final orders of removal residing in the United States, 1,441 of who have criminal convictions, according to ICE spokesman Brendan Raedy.

Community organizations have warned that 200 Cambodian nationals could be deported this year. ICE declined to comment on the figure, saying it would be speculation.

“Any removals would have to be coordinated with, and approved by, the Cambodian authorities,” Raedy said in an email.

Community response

Following the rise in detentions and deportations in the Southeast Asian community, a group of organizations submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to ICE earlier in April asking for detailed information about arrests, detentions and removals.

The Phnom Penh-based Khmer Vulnerability Aid Organization (KVAO), a non-governmental organization that assists deportees transitioning to life in the country, has also increased its capacity by renting additional space and hiring more staff, Bill Herod, an adviser to the group said in an email.

“In an average month, we currently manage around 200 client contacts, but that will increase greatly with so many new arrivals, each requiring – and deserving — individualized attention,” he added.

In 2015, the volunteer 1Love Movement joined the Southeast Asian Freedom Network in launching the #Right2Return Campaign to end the deportation of Cambodian refugees.

The following year, the group traveled from Philadelphia to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where they met with representatives from the Cambodian government to discuss ending deportations and renegotiating the 2002 repatriation agreement.

Sophea Phea — an organizer for the spin-off group 1Love Cambodia — said that while members of the group continue to be vocal about the impact of deportation on Cambodian refugees, its focus of late has shifted to providing aid for deportees. The group plans to become a non-governmental organization by the end of the year and work with KVAO, Phea said. One area they are currently focused on is obtaining identification documents for deportees, which are needed to secure employment.

Kum is among deportees waiting for his ID to be processed. In the meantime, he is receiving financial assistance from his siblings.

Since arriving, he has spent much of his time inside his condo and has been enduring a difficult adjustment to a completely foreign country, he said.

"It was really hectic, and I was starting to evaluate, 'Can I really live here?'" Kum said. "I still don't think that I can live here, but I don't have much of a choice.”

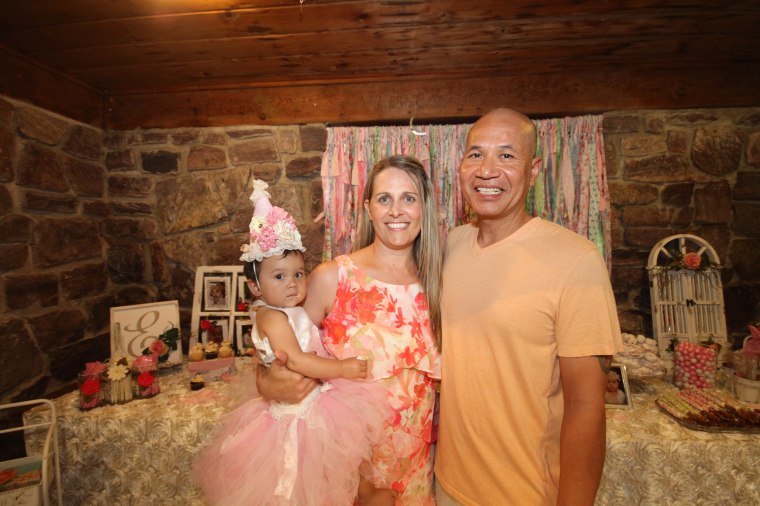

Sothy's teenage son, his wife, and their 19-month-old daughter remain in the United States.

Kum was born in Cambodia and fled the Khmer Rouge with his family on foot when he was no more than 2 years old, he said. They spent some time in Thailand and the Philippines before arriving in the United States when he was about 5 years old.

He was ordered for removal in 2016 and detained by ICE after serving a one-year sentence for possession of marijuana with intent to distribute. He remained in ICE custody until August 2017 and was re-detained in October 2017.

“Our entire family was extremely traumatized when they knocked on our door one morning and took him away from us,” Lisa Kum, his wife, said in an email, adding that it took several months before she stopped jumping at a knock at her door.

Kum said she and their daughter are planning to spend the summer with her husband. Next year, the two plan to move to Cambodia.

“We are sad and I miss my husband my daughter misses her daddy, but we will not let an unjust immigration system break our spirit,” she said.

Some families affected by the deportations have begun pushing for changes in laws that allow for the detention and deportation of refugees and lawful permanent residents, Mariategue, the immigration policy manager, said. SEARAC plans to help by funneling them through training programs and helping them engage with members of Congress, she added.

“We continue to call on this administration to re-examine the policies that they are claiming are just,” Mariategue said. “We are continuing to call on members of Congress to stand with these communities that came here as refugees, that have been victims of historical oppression, intergenerational trauma, and lack of support in their communities and in their school systems, and to really be champions for legislative fixes to these detentions and deportations.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.