Signs and artwork bearing the slogan “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” have begun appearing at protests and on social media following the death of George Floyd, a black man who was killed after a Minneapolis police officer knelt on his neck.

The slogan traces its roots to the 1960s, and while it’s being repurposed by Asian Americans as a show of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, some activists have begun speaking out against its use today, saying it detracts from the movement by equating Asian American struggles with black struggles.

“The false analogies end up getting us into trouble,” Connie Wun, co-founder and executive director of AAPI Women Lead told NBC Asian America. “Asian American and black communities may have some overlap, but these struggles are not analogous, and they’re not the same.”

The term “yellow peril” originated in the 1800s, when Chinese laborers were brought to the United States to replace emancipated black communities as a cheap source of labor. Chinese laborers made less than their white counterparts, and also became victims of racist backlash from white workers who saw them as a threat to their livelihood. This fear led to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the first law to restrict immigration based on race.

But in the 1960s, Asian Americans tried to reclaim the racist term and their histories. In particular, students of color at San Francisco State University and the University of California, Berkeley, formed a coalition called the Third World Liberation Front, calling for campus reform that included establishing ethnic studies classes and protesting the Vietnam War.

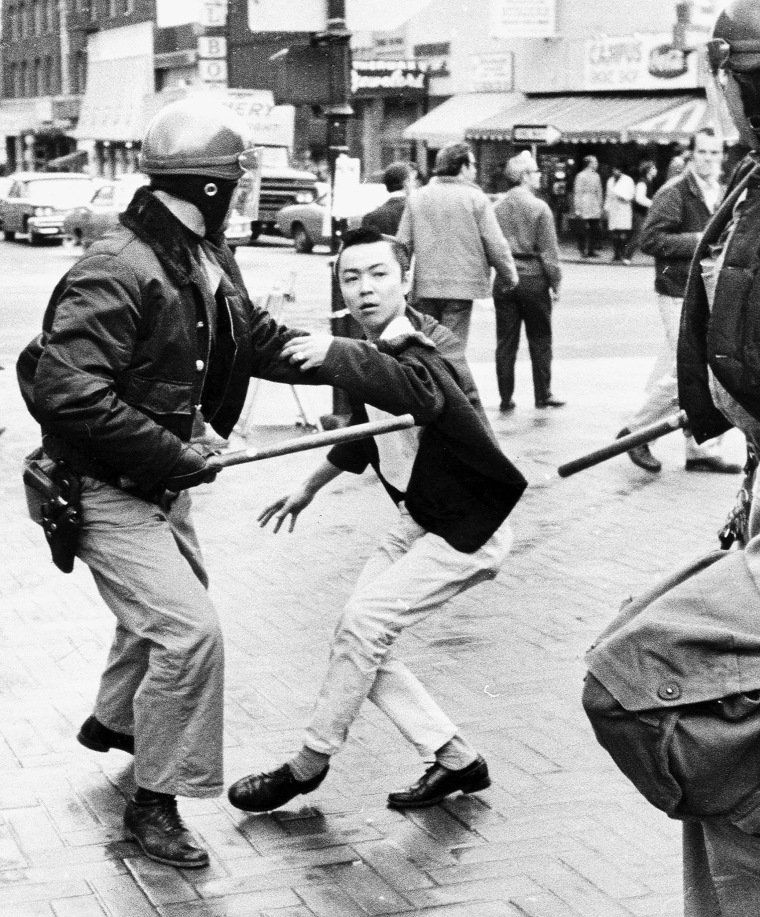

“Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” is most often associated with a black-and-white photo taken in 1969 at a rally in Oakland, California, supporting Huey Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, who had been arrested on charges of killing a police officer. (The other co-founder was Bobby Seale.)

In the photo, the sign is held by Japanese American activist Richard Aoki, who joined the Black Panther Party in its early stages and eventually rose in the ranks to become field marshal, making him the only Asian American to hold a leadership role in the organization. He’s also known as the person who first supplied the Black Panther Party with guns from his personal collection to use on patrols.

“At the very first Black Panther meeting, Richard was asked by Huey and Bobby Seale to speak about the history of the Japanese American concentration camps,” said Diane Fujino, an Asian American studies professor at UC Santa Barbara and author of Aoki’s biography, “Samurai Among Panthers: Richard Aoki on Race, Resistance and a Paradoxical Life.”

“The Panthers understood that racism against Japanese Americans and Asian Americans was linked to black liberation, and that these communities were both oppressed by white supremacy.”

While Aoki had been celebrated as a symbol for uniting Asian Americans and black Americans in their fight against white supremacy, in 2012, three years after his death, documents revealed that he had been an FBI informant tasked with infiltrating the Black Panther Party.

“It’s easy to teach the celebratory narrative — Richard presents a challenge to how we think about what it means to be an activist,” Fujino said. “The information puts huge question marks on his work and takes away from his legacy.”

While at the time, “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” was a way for Asian Americans to voice support for black communities and unite against oppressive forces, activists point out that today, Black Lives Matter is a different movement in a different era.

“The slogan has galvanized people, and I don’t discount its power in that sense,” Wun, of AAPI Women Lead, said. “But there are limitations to symbolism. We need to consider the fact that today, there are a lot more Asian Americans who don’t identify as yellow, or East Asian, so the term ‘yellow peril’ isn’t inclusive. We also need to interrogate how our privileges as Asian Americans are made possible by anti-blackness.”

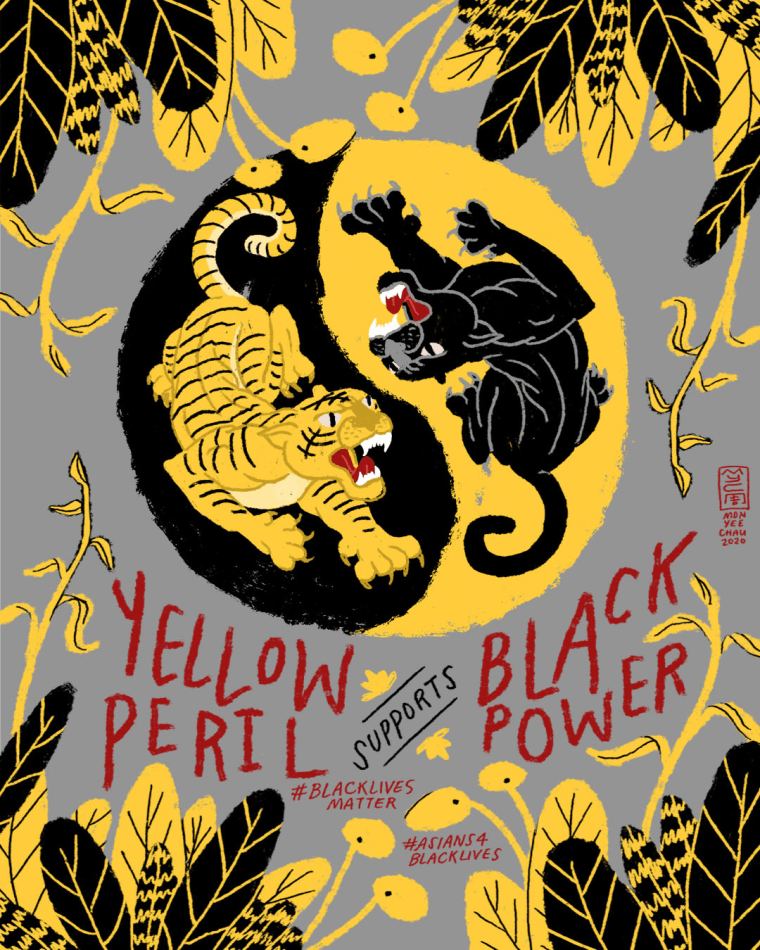

Monyee Chau, a Seattle-based Chinese and Taiwanese artist, is one of the artists who repopularized “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” after designing a poster of the slogan under images of a black panther and a yellow tiger. The image garnered more than 50,000 likes on Instagram. Chau, who uses the pronouns they and them, also made the artwork available to download so others could use it on posters and signs.

Chau initially designed the image in response to the “grief and anxiety” they felt after Floyd’s death on May 25, but soon started receiving messages from some who disagreed with the use of the slogan.

“Because I knew the slogan was used to express support for the Black Power movement, my intent was to offer the same support,” said Chau, who has since archived the original post and created a new image replacing the slogan with “Black Lives Matter.” “But I started having discussions with the people who messaged me, and I then understood how the phrase centers Asian Americans when this time isn’t about us.”

In their public apology, Chau also recognized ’the labor, patience, and opportunity for learning that Black and Asian femmes have granted’ them. A Black Asian person specifically worked with Chau to help them understand the implications of the slogan.

They pointed out on Instagram that black and Asian people have done the work of helping them understand the mistake. "I am grateful for the Black and Asian femmes who have cared enough to extend labor in allowing me and my community to have this opportunity to learn."

For Asian Americans who are seeking for ways to ally with black communities, Wun challenges individuals to think about whether their actions work to combat police brutality against black people, or if they’re centered around their own feelings.

“People have to center black liberation and freedom in their politics and in their practice,” she said. “That’s what it means to be in solidarity. It’s not going to be easy, but that’s part of the work. Racial solidarity is a goal that requires struggle.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.