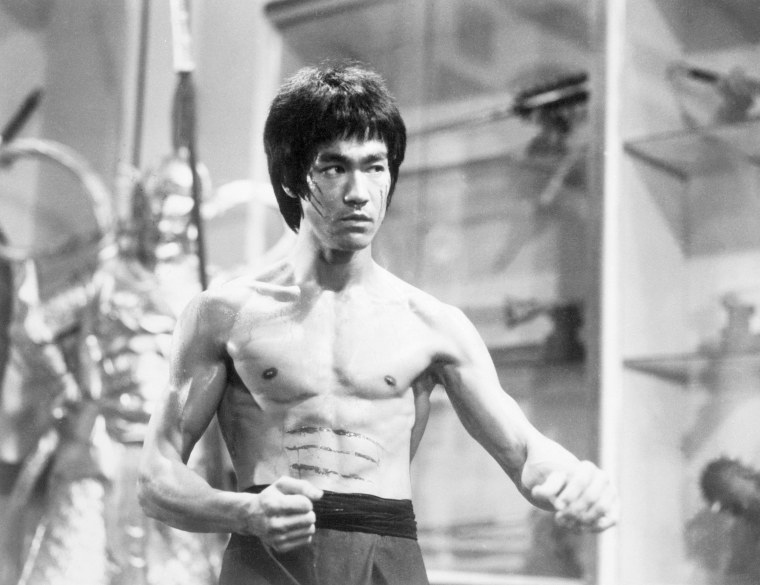

With his striking moves, unrepentant love for his heritage and timeless wisdom, Bruce Lee has long been a source of pride for Asian Americans who’ve looked to him as an emblem of power when they felt rather voiceless in a country that did not always accept them.

But Lee’s legacy has always extended across color lines, with the martial artist and actor attaining legendary status among many different groups, particularly African Americans.

Bao Nguyen, the director of a documentary on Lee, “Be Water,” that premiered Sunday on ESPN, told NBC Asian America that the martial artist’s legacy as a hero for those of diverse backgrounds remains important today, particularly in light of the nationwide demand for justice after the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police. From Lee's eagerness to listen to his black peers, to hitting back at oppression both on screen and off, he persists as a symbol of allyship with the black community nearly a half century after his death at 32, in 1973.

“His interactions with so many different people and his willingness to learn helped him become a good ally,” Nguyen said of Lee. “As Asian Americans, we need to be allies.”

As the director explained, Lee’s understanding of the systemic oppression that African Americans were facing at the time was largely influenced by students and friends who had confronted those very challenges in the civil rights era. One of his first students was Jesse Glover, who would go one to be Lee’s first assistant instructor in the United States. Glover, a black man, had been a victim of police brutality.

“One of the reasons that Jesse started learning martial arts was self defense as a way to defend himself against future incidents of police brutality,” Nguyen explained. “That really informed Bruce about race relations in America and kind of the fragility of it, especially for people who are not white.”

Among Lee’s most publicized friendships was with the Hall-of-Fame NBA center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who also used his voice to become a civil rights advocate. Abdul-Jabbar, who boycotted the 1968 Summer Olympics in protest of injustices toward black Americans among other forms of activism, would discuss social issues with Lee. But Nguyen stresses that Lee wouldn’t lean on his famous friend to do the work of breaking down every issue from the black community’s point of view.

“Bruce was taught a lot by Kareem, but Bruce would just go out and get books on his own after a while,” the director added. “We have to kind of self-educate ourselves, too, if we want to be good allies, to not put the burden on the African American community who have gone through so much already.”

But Lee’s understanding of race was also colored by his own experiences, growing up as a multiracial kid in Hong Kong. His mother, Grace Ho, was of European descent and because he wasn’t fully Chinese, Lee endured bullying as a child. His philosophy of always seeing someone for “their character rather than the color of his skin” has its origins in his upbringing, Nguyen said.

Later on in his life, Lee encountered layers of racism in Hollywood, enduring the emasculation of Asian men and lingering anti-Asian sentiment that had roots spanning back to the Chinese Exclusion Act era in the 1800s. Those issues reverberated throughout Lee’s career. While Lee was up for the lead role in 1970s television series “Kung Fu,” he was ultimately passed over, with a white actor, David Carradine, nabbing the spot.

“Asians were just not seen that way. They never played a heroic role in the mythology of America,” the director added.

What’s more, Lee refused to accept roles that featured Chinese people in a negative light, and in doing so, lost out on certain opportunities. He ultimately moved back to Hong Kong due in part to the difficulty in finding appropriate roles.

The lessons Lee learned from his exposure to different cultures and the racism he witnessed was often demonstrated in his work and teaching. Daryl Maeda, an assistant professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado-Boulder, who’s writing a book on Lee, described the martial artist as a “consummate mixer of cultures.” Lee would combine fighting styles from various traditions, not only using movements from China, Japan and the Philippines, but also supplementing his martial arts with Western styles like boxing and fencing.

That mentality could be seen on screen as well, Maeda said.

“He preached constantly that in martial arts, distinctions of race and nation must be discarded,” Maeda said. “In ‘Way of the Dragon’ he admonishes a student who says he prefers Chinese boxing -- Kung Fu -- over Japanese karate because the latter is 'foreign.' His character, Tang Lung, replies that nothing is foreign, everything must be evaluated on how effective it can be in particular circumstances.”

Lee also took his fight against racism before the eyes of his audience. Nguyen notes that the star’s first two major films centered around beating back against oppressive systems. His 1971 movie “The Big Boss,” featured Lee fighting on the side of laborers against a crime boss, while “Fist of Fury,” which came out a year later, showed the martial artist fighting against Japanese colonialism and the discrimination of Chinese people.

In “Enter the Dragon,” Lee, who produced and starred in the film, showed the symbiotic relationship between colonialism and racism, Maeda said. It included direct references to police harassment of black people and also the black martial arts movement.

“Although the racial politics of the film are far from perfect, he creates a filmic partnership between Asian American and black protagonists that gestures toward what is possible,” the scholar said.

The messages in Lee’s movies were often parallel to fight for civil rights in the U.S., Maeda said.

“This was in the era of Black Power and its emphasis on self-determination and resistance in the face of a white supremacist society,” Maeda said. “Many black activists and organizers recognized in Lee a kindred spirit.”

In addition to Lee’s films being largely distributed in theaters that catered to black communities, Maeda argues that ultimately what Lee stood for and the themes woven throughout his movies contributed to his legendary status among black Americans. He explained that Lee, a racialized subject who consciously protested the discrimination he confronted, was a particularly poignant image for many viewers.

“African American audiences saw in him a nonwhite underdog fighting for recognition on the screen and in real life,” Maeda explained. “Black moviegoers could see in Bruce a man of color struggling for self-determination and power.”

Nguyen emphasized that in some ways, Lee is remembered today as a global, cultural icon who has transcended race. In reality, the martial artist was judged on his appearance and accent in 1960s America. As the country tends with systemic racism and discrimination of the black community, the director noted that he hopes people remember real change isn’t supposed to be comfortable.

“He didn't just make it in Hollywood because of the charisma and the confidence he had of himself,” Nguyen affirmed. “That should be a reminder today that progress doesn't come easy.”