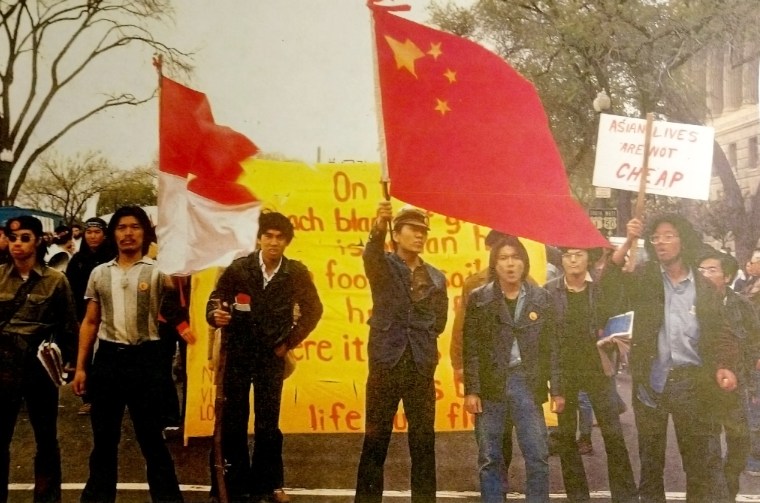

Corky Lee often photographed the underchronicled stories: a young child with her mother in a sweatshop, a protester with blood rushing down his face and a re-enactment ceremony for the Chinese immigrants who were excluded from photographs of the completion of the transcontinental railroad.

Behind his retro wire-rimmed glasses and signature Hawaiian shirts, Lee — who died last week at age 73 after having struggled with Covid-19 — had borne witness to many inequities in Asian America, leading him to define his work as "photographic justice."

"He's like Johnny Appleseed," said Viktor Huey, a longtime friend of 50 years. "He would go around and spread ideas so the seed would grow. I'm not saying that all he did was take pictures. I'm saying that he saw a problem and then had solutions."

"He's like Johnny Appleseed," said Viktor Huey, a longtime friend of 50 years. "He would go around and spread ideas so the seed would grow.

Lee was born in Queens, New York, as Young Kwok Lee, which translates to "rebuild a nation." He was the second child and the oldest son of immigrant parents who hailed from the agrarian village of Toisan, China. His father, Lee Yin Chuck, owned a hand-laundry business, and his mother, Jung Shee Lee, was a seamstress.

For half a century, Lee documented the Asian community across the United States as a self-taught photographer, capturing moments of injustice from the grim recesses in lower Manhattan to the golden spike at Promontory Summit, Utah.

Against the backdrop of the post-1960s civil rights movement, the 1970s Chinese cultural revolution and anti-Vietnam War protests, Lee picked up his lifelong calling in photography at a time of youth revolution.

After he graduated from Queens College as an American history student in the early 1970s, he started taking pictures to fight for tenant rights in the Lower East Side.

"He felt it was an injustice — a big corporation buying up buildings in the heart of the residential Chinese community, evicting them and then sealing off these buildings," said Virgo Lee, another longtime friend, who met Corky Lee in an organization effort that tore down the boarded-up buildings to house squatters.

He recalled Corky Lee's arriving on the scene with a borrowed camera to document the group's efforts one day.

"The funny thing is nobody really knew what was motivating Corky to start taking all these photographs," Virgo Lee said.

As Corky Lee recorded the deplorable housing conditions and the group's activities to send to local news organizations, the conglomerate eventually backed off, fearing bad publicity, and sold the buildings.

A year later, Corky Lee played an active role in the logistical planning of the first and largest Chinatown street health fair, held by a majority of college student activists concerned that residents lacked access to basic health care.

The fair, which hosted free health screenings and blood pressure tests, took in enough money to open the Chinatown Health Clinic. The Charles B. Wang Community Health Center of today, which largely caters to medically underserved Asian Americans, grew out of the earlier effort.

"He was there recording everything," Virgo Lee said, recalling how Corky Lee documented the progress to the fruition of the clinic.

Even when Corky Lee was hustling in sales and customer service at Expedi Printing by day and as a photographer at night, he channeled any residual energy to address injustices.

Huey stressed the role Corky Lee played in prompting the first Chinese translations on ballots in the city in 1994. The New York City Board of Elections had long refused to provide Chinese translations of candidates' names in voting machines in districts where many Chinese lived, citing a lack of room on the ballots and the printers' inability to produce Chinese characters.

With the expertise he garnered at his day job, Corky Lee squeezed Chinese characters into a sample ballot for the board.

"We got a printer, Corky Lee, and a graphic designer, Ed Lai, to make a ballot with the exact specifications to show that it could fit in the chute of the machine," the executive director of the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund told The New York Times in 2009, without having to explain who Corky Lee was.

"We got a printer, Corky Lee, and a graphic designer, Ed Lai, to make a ballot."

Huey said: "This had nothing to do with photography. This is just Corky being active, seeing a problem and then addressing it."

Meanwhile, his fame as a photographer spread through word of mouth as he carved out the time to appear in every Asian American event before his work grabbed the attention of the news.

"It didn't matter to him whether there were going to be five people or 500," said John Lee, the second youngest and only surviving brother in the family, whom Corky Lee called "Johann." "If it was an issue that impacted Chinatown or the Asian American community in any significant fashion, he was there to cover it."

Virgo Lee said: "If you're the only person that went to every single Asian event, then yes, the word is going to spread that Corky is the one that has pictures. Nothing can stop this guy."

That meant working extra hours the day before to cut to a demonstration during his early years or shimmying up a lamppost to score the best shot in his later years, even if it led to occasional injuries.

Virgo Lee said there was never a time when Corky Lee stopped or disappeared from the scene, except when he was greatly affected by the death of his wife, Margaret Dea, in 2001.

"He went into a deep funk," said Huey, who said that it was only after he met Karen Zhou, his longtime partner, that Corky Lee was reinvigorated to emerge from his shell as a photographer.

Zhou, also a photographer, had always appeared in the growing number of exhibitions and shows Corky Lee held over the years.

"At the end of an event, we'd scan the crowd to look for each other," she said, recalling how the pair would sit down, edit and quibble over each other's photographs. "With him gone, it won't be the same. There is this void."

"He had no huge platform other than his camera, his being and his efforts. But through that, he has touched millions of lives,” said Jennifer Takaki, director and producer of the documentary, “Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story."

Jennifer Takaki, the director and producer of the documentary, “Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story,” which led her to follow him for 18 years, said he was humble but was truly worthy of his self-appointed name “the undisputed, unofficial Asian American photographer laureate."

“He wasn’t famous per se, right?," she said. "It's not like he had a household name. He had no huge platform other than his camera, his being and his efforts. But through that, he has touched millions of lives.”

As open and engaging as he was, he kept his private life exclusively to himself and peppered his conversations with sage stories, historical facts and cultural details – all with an avuncular warmth and crisp memory that invited people in.

“I think everyone has a unique, funny and amazing story about Corky,” Takaki said. “Everybody felt special to Corky. He united people and made them proud of who they were. It's very rare to meet someone who seems to have all the time in the world for everyone. Corky was there for everyone. I think that's why it hurts the community so hard because he has always been there.”