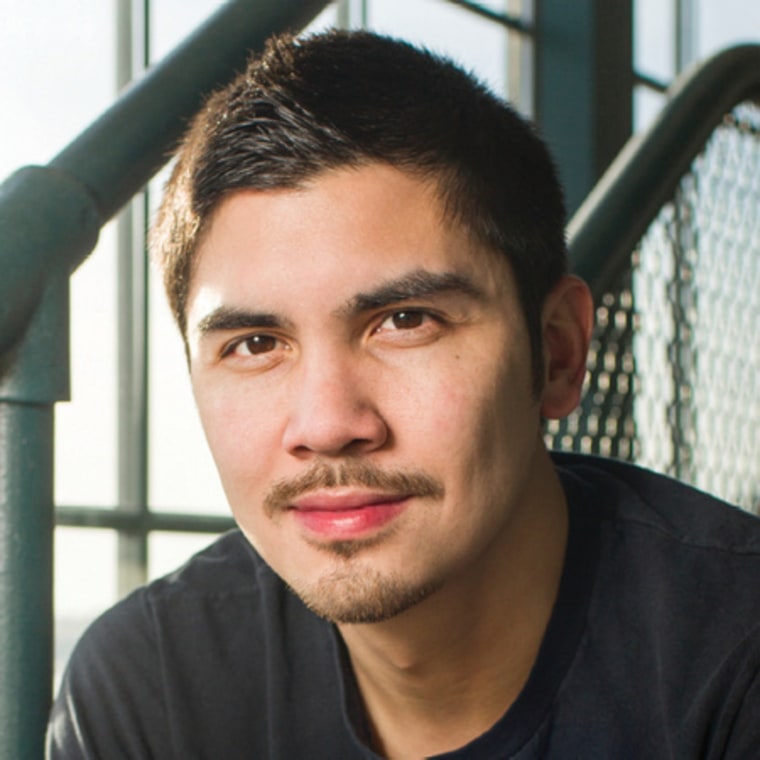

Randy Ribay remembers the anger he felt when he first read about the drug war in the Philippines a few years ago.

“There was an immediate reaction of ‘this is wrong, there’s no due process, this is an abuse of human rights,’” the author recalled. “So it kind of shocked me when you’d see independent surveys saying 80 percent of Filipinos support the policy.”

Started by Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte in 2016, the drug war grew from his campaign promise to rid the country of illicit drugs and urging people to kill both criminals and drug addicts.

It has resulted in thousands of deaths and has been denounced by human rights activists and world leaders. As Ribay followed the news from his home in the Bay Area, he was startled to learn that almost all of his relatives in the Philippines supported the measures.

“The question that came up was that, as a Filipino American — I was born there but I’ve lived primarily in the United States, ‘What’s my right to voice my opinions on those matters or to advocate against certain policies in the Philippines?” Ribay said. “I just started wondering about what it would be like to be a teen right now struggling with that question.”

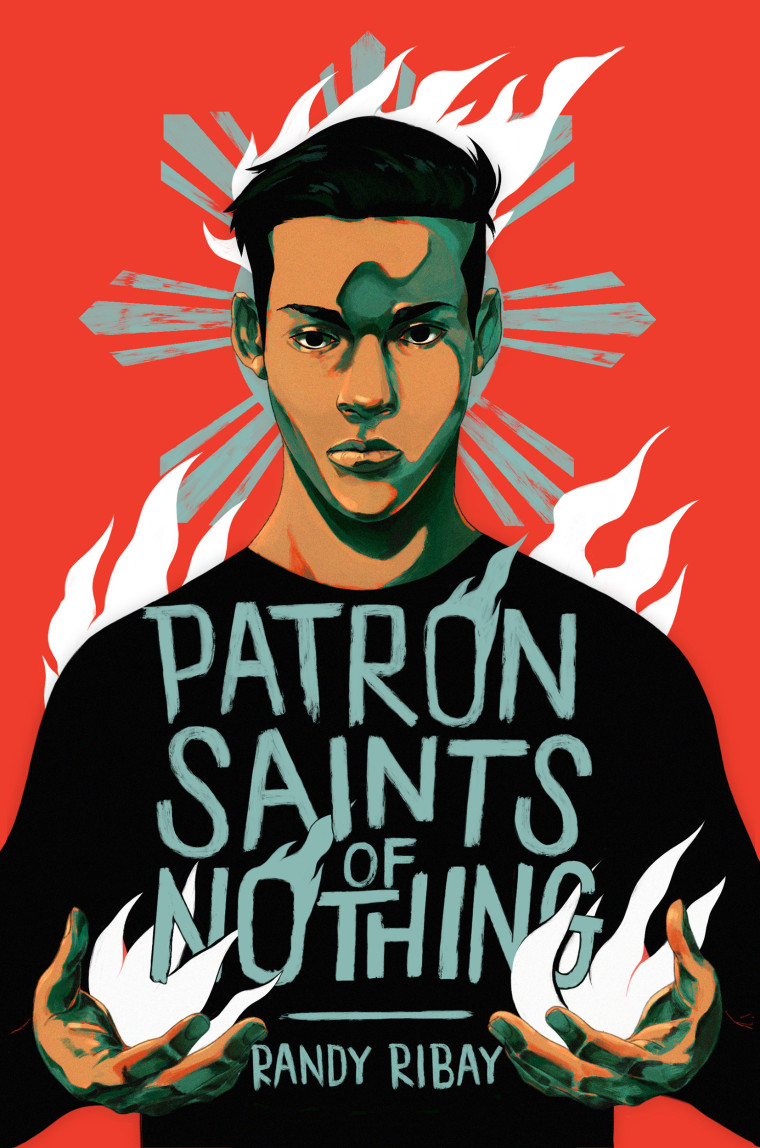

That exploration lead Ribay to begin writing his latest novel, “Patron Saints of Nothing,” which is set to be released June 18 by Kokila, an imprint of Penguin Books. In the novel, Ribay explores the story of the Filipino American teenager Jay Reguero, whose world is shaken to the core when he learns that his favorite cousin, Jun, died mysteriously in the Philippines. When no one in his family will talk about what happened to Jun, Jay decides to drop everything in the middle of his senior year to travel to his parents’ birthplace and investigate on his own.

As Jay heads to his uncle’s house and begins to uncover what really happened to Jun, he realizes that things are more complicated than he expected them to be. “I wanted to position Jay as a learner,” Ribay said, noting that while Jay’s journey was an extreme one, the questions he had about identity were ones that many second generation Americans often experience.

Born in the Philippines to a Filipino father and a white mother, Ribay and his family moved to the U.S. when he was a small child. They would periodically visit throughout his childhood. The author of two other books for young adults, Ribay says that in many ways “Patron Saints of Nothing” is his most personal work yet.

“First and foremost, I was writing it for Filipino Americans, that was the primary audience in mind — Filipino American teenagers,” he said. “Because I didn’t have that mirror growing up. I don’t remember reading a single book featuring a Filipino until I got to college.”

Ribay had a bit of an advantage when it came to capturing the voice of modern day teens in his manuscript: He’s been a high school teacher for 13 years. “For better or for worse, the teenage voice is in my ear all day long,” he said. “I’ve seen slang come and go.”

But researching the drug war and how to portray modern Filipino life accurately took much more research.

To create the scenes retracing Jun’s life before his death, Ribay read articles from both Western and Filipino sources and traveled to the Philippines in the summer of 2017 to do firsthand research, speaking with a former activist during the regime of President Ferdinand Marcos, as well as a journalist with extensive experience covering the drug war.

To get a sense of what the fictional Jay’s aunt and uncle think about the drug war, Ribay also spent time during his trip talking to his own family members about why they supported Duerte’s policies. “Within my own family who lives in the Philippines, there was only one cousin that I knew of who was against the policy,” he noted.

That was one of the reasons Ribay tried to create a nuanced portrayal of the Philippines and why his favorite scenes shined light on the “softer, happy moments” Jay experiences with his family during his visit. Ribay said it was particularly important to him to include those moments so that readers who are unfamiliar with the Philippines could get a fuller picture of what it's like there.

“There’s kind of this tendency to reduce that culture to only the most painful aspects of it — to reduce the Philippines to poverty or to the drug war,” he said. “I wanted to include those moments that don’t necessarily add a whole lot to the plot but were quieter with his and share the joyous side.”

Ultimately, Ribay wants other young Filipino Americans to connect to Jay and his search for answers to both his cousin’s death and his questions about his own identity.

“It’s difficult to figure out and a lot of time your family can’t help you figure it out because they don’t know,” Ribay noted. “When you are the first multinational generation, you’re the one who has to figure that out.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.