“Endlings” is a play about endlings, the last members of a species, destined for extinction.

It also could have been an endling itself. Playwright Celine Song, 30, said she was falling out of love with theater when she wrote “Endlings” as a member of the Emerging Writers Group at the Public Theater three years ago.

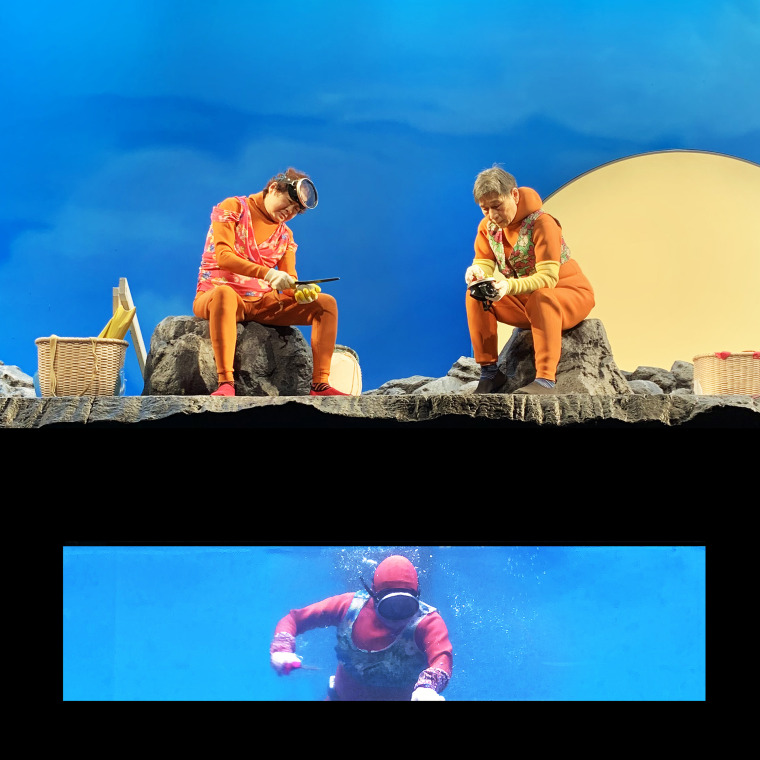

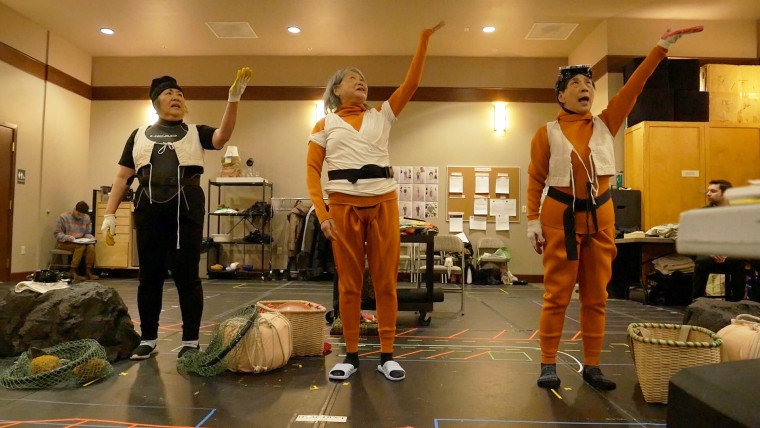

Because she thought it might be her last play, Song didn’t focus on writing something that would be easy to stage. Instead, she let loose and wrote something she called “unproducible.” The play takes place in the ocean, in houses on the beach, in apartments, and in theaters. Its stage directions command characters to “[dive] into the ocean,” and the script includes casting notes that call for three elderly Asian (“most ideally,” Korean) actresses who can, Song noted, not only memorize long monologues but also swim.

“Every casting director would tell you — even the amazing ones who are very good at casting people of color — that it’d be a difficult group to cast,” Song said.

The play, which begins previews Tuesday at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is expected to be Song’s highest profile opening yet. The cast includes an actress from the Marvel TV universe and a beloved actress with a recurring role on “Gilmore Girls.” The play's director was also recently named to Forbes’ 30 Under 30 list. And, if that wasn’t enough, a 4,800-gallon water tank has been built on stage to represent the ocean.

“I — first of all — didn’t believe them,” Song said about when she first learned that the American Repertory Theater was interested in staging the play. “I thought, ‘This woman was lying to me.’ I just didn’t believe her until I saw that set.”

The first half of “Endlings” follows the fictional twilight years of the last three remaining “haenyeos,” a real group of women from Korea’s rural southern islands whose livelihoods depend on free diving for extended periods of time to gather seafood. A centuries long tradition which once included tens of thousands of divers, 2017 estimates put today’s figure of haenyeos between 2,500 and 4,000, with most advanced in age.

The play’s three haenyeos — all of whom are older than 70 — banter about their work, the drama of television, whether or not they beat (or would beat) their children, and their dead husbands.

Part way through the first act, the audience is introduced to Ha Young, a Korean-Canadian playwright in Manhattan who is writing about the haenyeos and is an analogue for Song. In the second act, Ha Young reflects on the first act of the play the audience has just seen, which she has also just finished writing. She explores the meaning of power, who has the freedom to do what based on where they’re born and the buildings they live and work in, and what it means to tell an “authentic” story.

Knowing that “Endlings” could be her last play pushed Song to explore areas she hadn’t before, she said, including her first time writing anything connected to her Korean identity.

“I felt more vulnerable but more invincible,” Song, who was born in Seoul and immigrated to Canada at the age of 12, said. “I wasn’t posing as anything … but, of course, with any act of honesty, it makes you more vulnerable.”

“But I did not care,” she added. “I needed to write this play.”

Song was inspired to write about haenyeos after watching a documentary about them with her mother, she said. Song recalled the documentarians pushing the haenyeos to talk about how much they loved their work and how beautiful it was while the haenyeos instead talked about how hard the work was and how happy they were that their children took different paths.

She was particularly struck by how different her life was from theirs, despite SHARING A Korean background. Haenyeos make barely $3,000 a year, an amount Song was spending a month to rent an apartment in New York City -- an apartment whose bedroom could barely fit a full bed.

“‘Endlings’ is a play about elderly Korean female divers on a very small island six hours away from the mainland,” Song said. “It’s also about me, who is a playwright living on a different island — Manhattan — writing about it. It’s about immigration, because I am an immigrant.”

Wai Ching Ho, who plays Han Sol, the oldest haenyeo, noted that her character’s actions ran parallel to the immigrant experience. Han Sol has children and grandchildren, but they live far away.

“I think almost all the haenyeos, they don’t want their children to follow in their paths,” Ho, who was born in Hong Kong and has lived in new York for upwards of 50 years, said. ”They want to move away and get a better life ... that’s where immigrants all start, they want a better life for their children. It’s not for themselves. There may be sacrifices, but for their children, they want the best.”

For Ha Young, the playwright character representing Song, much of the second half of the play is spent exploring what it means to tell an “authentic” story and why the character would want to.

The second act opens with the character and her husband, who is white, discussing the first act. The pair argue about whether the husband actually likes the play as he says he does. Ha Young notes that when her husband likes her work, he normally acts jealous, but this time he was not. Her husband counters that, as a white person, “there’s no way [he] could have written” the play, so why would he be jealous?

The conversation largely mirrors one Song had with her own husband after she finished writing the first act of “Endlings.” Song recalled hitting being stuck on how to proceed with the play, but after that conversation, she stayed up all night to finish writing.

“I think that I had taught myself not to talk about my identity,” Song said, noting that growing up as an immigrant, she learned that white families are considered the norm.

Part of writing “Endlings” meant undoing that. Part of telling an “authentic” story is being genuine and not holding back, Song said.

“This play taught me how to feel powerful,” she said. “Talk about what you want to talk about. Share what you want to share.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.