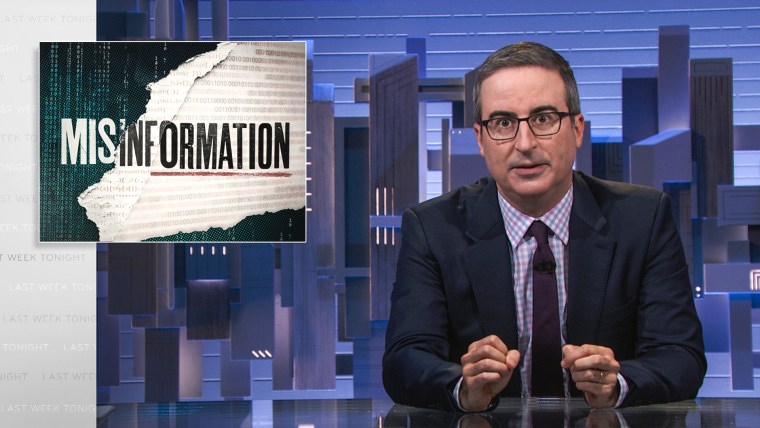

John Oliver tackled misinformation circulating in immigrant communities during a segment Sunday on HBO's “Last Week Tonight,” calling attention to Facebook, WhatsApp and WeChat as top offenders in allowing fake news to make the rounds.

While Facebook, which owns Instagram and the popular global messaging service WhatsApp, makes headlines over its handling of fake news, Oliver noted that the company’s efforts often leave out content that isn't in English. A bulk of users live outside of the U.S. or in non-English-speaking communities, he said. And though they find their feeds filled with the same conspiracy-laden posts, there are little to no flags or disclaimers by the tech giant.

“There needs to be public pressure on platforms to do something about all forms of misinformation whether they are in English or not,” Oliver said.

Facebook says combating vaccine misinformation is a high priority and that the company has removed more than 20 million pieces of content that break the guidelines, a spokesperson told NBC Asian America.

“Ever since the pandemic began, our goal has been to keep everyone safe by promoting reliable information about Covid-19, taking action against misinformation, and encouraging people to get vaccinated, not just in English-speaking communities but across the globe," a Facebook spokesperson said.

The company also instituted a policy that restricts WhatsApp users from forwarding a message to more than five chats at once. Oliver acknowledged that change but said it wasn't enough, noting the same message forwarded by multiple users to five different chats still has the potential to reach millions.

WhatsApp forwards, long messages and images that tend to make the rounds in South Asian circles, are often innocuous. Oliver poked fun at the auntie-style “Good Morning” videos and gifs that young people might wake up to in their family group chats.

But the threads can also be a digestible way to expose people to false information, particularly surrounding elections and the pandemic. In India, WhatsApp group messages have even been linked to mob violence; altered videos claiming to show a kidnapping led to the murders of over two dozen people in 2018.

Oliver also addressed WeChat, a Chinese messaging, payment and social media app with over a billion users worldwide. Most users posting articles to the app aren’t allowed to include hyperlinks, making it easy to disguise misinformation and spread it widely.

“It’s really easy for you to forward something to many groups and reach thousands of people at once, and then those folks forward on to their many groups and so on and so forth,” Priscila Neri, a program manager with Witness, a nonprofit human rights organization, told NBC News in 2018.

Oliver drew attention to Reddit threads like r/AsianParentStories where first-gen kids discuss how these messaging apps have changed their parents’ politics and ways of thinking.

“It can be truly exasperating for younger people to see just how susceptible their relatives are to this bulls---,” Oliver said.

And while U.S.-based conspiracy theorists have dozens of fact checkers to answer to, foreign language outlets don’t. Vietnamese-speaking communities, for example, have the Interpreter and Viet Fact Check.

“But these are often small organizations, and the people running them are outmatched,” Oliver said.

An ad campaign released by WhatsApp in India in 2018 encouraged young people to explain to their older relatives why spreading misinformation is dangerous, but Oliver said the tech giants that run these platforms need to take the initiative themselves.

“Ideally, platforms like Facebook, YouTube and others would be at least as proactive about taking down misinformation in other languages as they are about taking it down in English,” he said.

But despite information campaigns and new regulations in place to report and flag content, the casual and intimate nature of messaging groups makes users all the more vulnerable to falsehoods.

“Political messaging operations use these services to spread disinformation about opponents and groups, which has led to violence,” Joan Donovan, a former researcher at Data & Society and now at the Harvard Kennedy School's Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, told NBC News in 2018. “Because the messages tend to come from trusted sources ... it presents a new challenge for stopping the influence of disinformation on the public.”