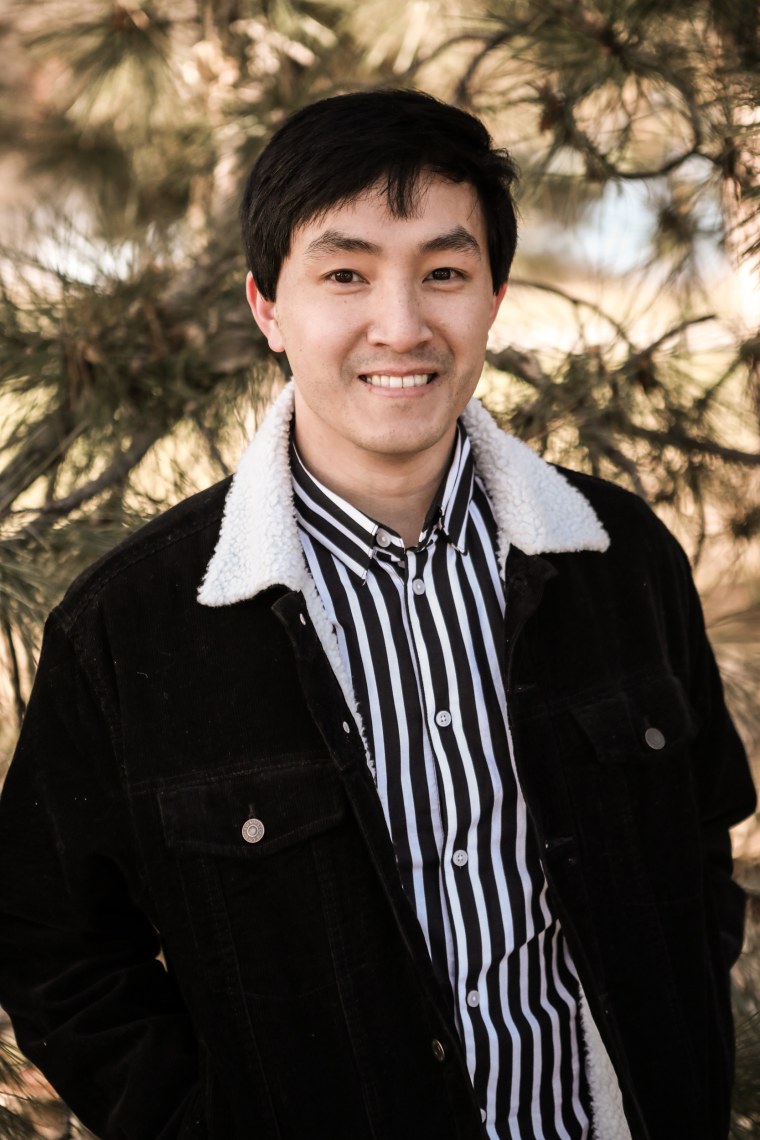

For writer and artist Trung Le Nguyen, sharing stories was always a way for his family to learn and grow together.

Nguyen, who was born in a Vietnamese refugee camp in the Philippines, moved to the United States with his family as a young child in 1992. "My parents would take me to the library a lot as a little kid, and they were learning English alongside me," Nguyen said. "We went through the process of shoring up our literacy together."

But when he decided to come out to his parents as gay a few years later, he struggled to find the words in Vietnamese — literally.

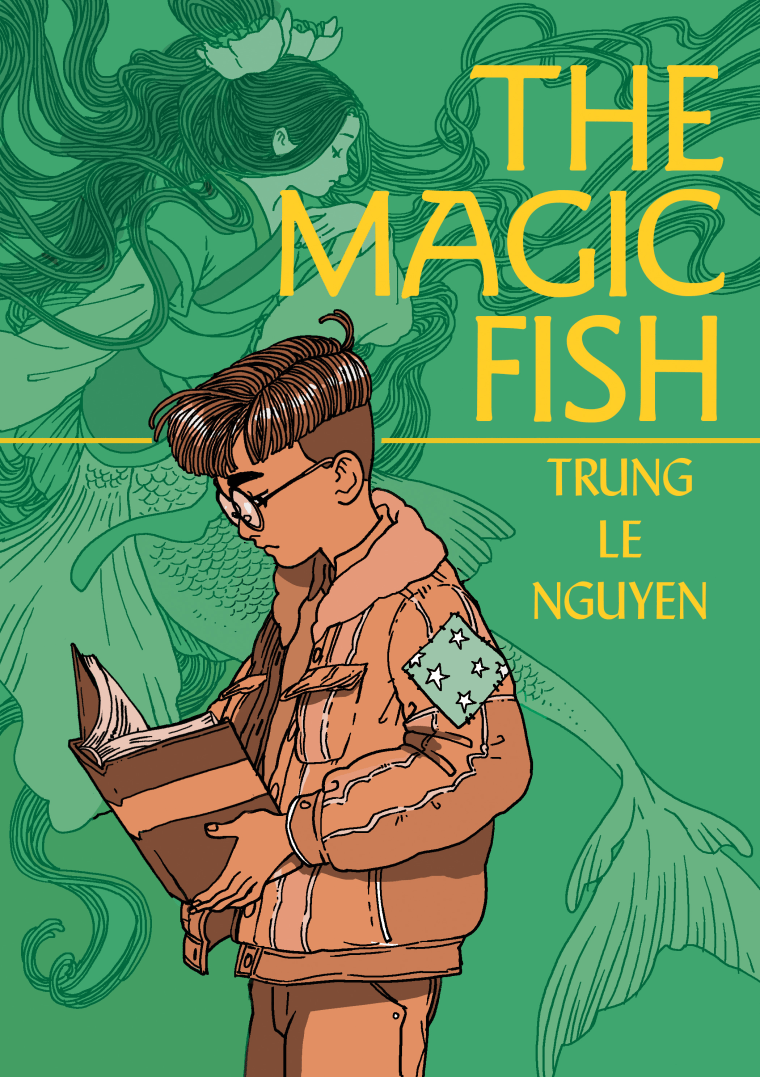

Memories of his journey to discover the right vocabulary to discuss his life with his parents were part of the inspiration behind "The Magic Fish," Nguyen's new graphic novel about a Vietnamese American boy's coming of age, which will be released by Random House Graphic on Tuesday.

National Coming Out Day is Sunday.

The struggle to find the right vocabulary to describe same-sex attraction or nonbinary identities is shared by many Americans whose families speak Asian or Middle Eastern languages at home. Many have said they are often at a loss to find terminology that is both accurate and affirming in their ancestral languages, because the existing vocabulary is nonexistent, stereotypical or offensive.

Community advocates say that's why in the last several years many advocates have been working to create more inclusive words and phrases that fully encompass the LGBTQ umbrella. For instance, some in the Filipino transgender community have started using the words "transpinoy" and "transpinay" — which build off the words for "Filipino" and "Filipina" used by people in the Filipino diaspora — because the existing terminology is considered a slur.

"Oftentime, people come out in very isolated little islands, and it is very hard because of that isolation initially," said Ameera Khan, an activist with the Muslim Youth Leadership Council, which works on LGBTQ, sexual health and reproductive rights issues. "But as the community grows — and there are communities in every ethnicity across the globe — that makes their culture almost countercultures with their own language."

Khan, who is Bangladeshi American and grew up speaking Bangla, Urdu and Arabic in addition to English, said finding others who share a language and culture can often help break that isolation.

Using only English words to describe one's sexuality or gender identity when talking to relatives can "reinforce this idea that queerness is a Western idea," said Amina Mohammad, a fellow member of the Muslim Youth Leadership Council who asked that she be referred to by her first and middle names because she has not come out to her family.

That can be especially problematic because "a lot of immigrant communities say things like 'this is not part of our culture, this is an American thing'" when a child comes out, she said.

In one of the more poignant moments in "The Magic Fish," Tien visits the library and asks for help looking up the Vietnamese word for "gay." He feels discouraged when the librarian cannot find one and later confides to a friend that he feels particularly bad that he came out to the librarian before he spoke to his own parents.

"There are a lot of layers to it that I wasn't expecting to peel back while I was telling the story," Nguyen recalled of creating the library scene. "Because there is no common language, he has to seek help elsewhere."

Years after he came out to his family, Nguyen remembers asking his mother why he could never find the Vietnamese words he was looking for in the library back then.

"She said, 'Well, there are euphemisms for it, but I don't know any actual words for it,'" he said. Nguyen said he is encouraged by the emergence of an LGBTQ movement in Vietnam that is creating words and phrases to describe their lived experiences. "But I don't know where the culture was in the '90s," he said. "My parents certainly weren't aware of it, either."

That experience is one many Asian American families — regardless of their countries of origin — can relate to. While communities in Asia may change their language usage, immigrants usually use only what they learned before moving, said Aruna Rao, founder of Desi Rainbow Parents and Allies, a South Asian American LGBTQ support organization. When the group's members began translating materials into Hindi and other languages, they quickly realized how delicate the task could be.

"Many of the words that we could find were just really formal, literary terms," which date back hundreds of years but are not in everyday use today, said Rao, who was inspired to start her organization after her child came out as trans. "There's a word in Hindi that literally means 'attracted to the same sex,' but those words made no sense to most people."

Rao said that because most languages that originate from the Indian subcontinent are highly gendered, describing nonbinary and trans masculine identities in South Asian languages is particularly difficult. She recalled that her 82-year-old mother struggled with which pronouns to use for her grandchild in their native Kannada, a Dravidian language that originates in South India.

"She struggled initially because my kid wanted to use they/them, and that became a whole other translation battle," she said, noting that the word for "they" is typically used as a sign of great respect and not for a grandparent talking about a child.

Rao said her child eventually decided to use the pronouns he/him because he was tired of being misgendered by his extended family. But it doesn't have to be that way. "For people willing to do the work, it is not that difficult in Indian languages," she said of finding the right pronouns. "There are ways to kind of use that language."

Another issue Desi Rainbow Parents and Allies had to navigate is how to best reflect the linguistic diversity of South Asia, because a word that makes sense in Hindi does not necessarily work well in other regional languages. The group is working on creating materials for posters and public service campaigns targeted to Indian American parents of LGBTQ children, a process that has taught it that the English terms "gay" and "LGBTQ" were understood in a way that South Asian words were not.

That is why, after having studied it and consulted with other members of the community, board members decided to transliterate phrases like "LGBTQ" and "gay" into Hindi and Punjabi scripts, because the general population was so familiar with those terms. The group is creating posters and other promotional materials using the transliterations and is planning to expand to other popular languages such as Bengali soon.

"I think that actually people are grateful to discard the older words and move towards English vocabulary that doesn't carry all of those connotations," Rao said.

Other communities are creating terms to positively reflect LGBTQ people. Amina Mohammad, who is Palestinian and grew up speaking Arabic, has noticed that many Muslim activists in the U.S. and abroad connect poems and songs by luminaries such as the 13th century poet Rumi and the 14th century poet Hafiz to the experiences of LGBTQ Muslims today.

"I like how a lot of queer activists in the Arab world ... are coming up with their own words that are not Arabizations of an English word," she said. In recent years, she said, she's seen the Arabic word "mithliyi" or "mithliyah," which mean "sameness," used to refer to gays and lesbians in the community. Those terms are also being adapted by Muslim American queer communities in the U.S., she said.

The globalizing influence of the internet and the fact that many Asian and Middle Eastern Americans continue to have connections abroad mean LGBTQ people on both continents continue to influence one another when it comes to language, culture and even politics.

Rao said that when India's Supreme Court ruled in 2014 that members of India's third gender could have their gender identity listed on their passports, she heard from many transgender Indian Americans and parents of transgender kids about how that led to increased acceptance and understanding in communities in the U.S.

"Before, it would be 'Oh, you crazy Americans,' but now it's like 'We know, because there is a pride parade in our city now' kind of thing," she said. "There is a bit more understanding back home."