When Sachi Argabright joined Instagram in 2018, one book kept catching her eye: Sayaka Murata’s “Convenience Store Woman,” the best-selling novel about contemporary work culture and conformity in Japan told from the perspective of a single woman who finds peace working at a rigid Tokyo convenience store.

“Everyone was talking about this book,” Argabright, a co-host of the Reading Women podcast and an advocate for translating Japanese fiction, told NBC Asian America. “All my extended family still lives in Japan, so it [literature] is a good way for me to get connected with that side of my heritage and culture.”

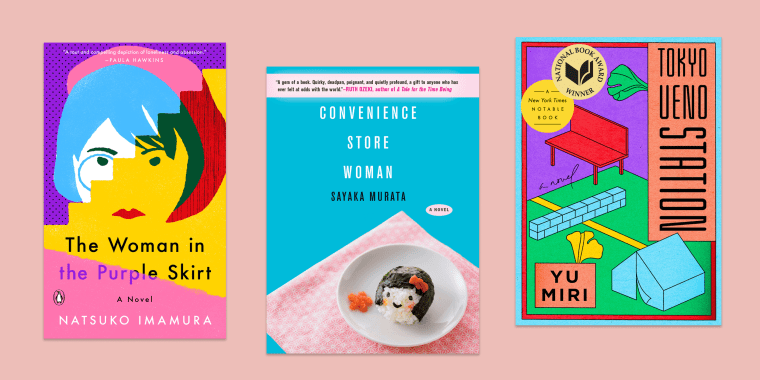

Experts say “Convenience Store Woman,” along with translators, social media and initiatives like Women in Translation month, are responsible for the increased American interest in Japanese fiction in recent years, particularly from works by women such as Mieko Kawakami, Natsuko Imamura, Hiromi Kawakami, Yu Miri and Yōko Ogawa.

According to “Publishers Weekly,” there have been more than 300 Japanese novels translated into English in the last decade. Ten years ago, only a handful of books written by Japanese women were published in English, but of the 34 titles translated from the Japanese in the last two years, 28 were by women.

Call it the Murata effect.

“Publishers used to ask translators for the next Murakami,” said David Boyd, who co-translated Kawakami’s breakaway hit “Breasts and Eggs” with Sam Bett and her 2009 novel “Heaven,” which was published in English this year. “For the past three years or so, they’ve been asking for the next ‘Convenience Store Woman.’”

Historically, Japanese fiction wasn’t popular in the West, but in 2005 Haruki Murakami broke through in America with “Kafka on the Shore,” translated into English by Philip Gabriel. His 2011 1,600-page novel “IQ84,” translated by Gabriel and Jay Rubin, and 2017’s “Men Without Women,” translated by Gabriel and Ted Goossen, went on to be national best-sellers (A new essay collection from Japan’s most celebrated author, “Murakami T,” translated by Gabriel, is being published on Nov. 23).

“Convenience Store Woman,” translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori and featuring a bright blue cover and a rice ball fashioned into a woman’s head on a plate, won the prestigious Akutagawa Prize in 2016, and sold more than 1.5 million copies in Japan. In the U.S. the novel was a Los Angeles Times bestseller and named a Best Book of the Year by the New Yorker.

“Now that publishers can actually see how readers engage with these books, they’re hungry for more,” said Boyd, an assistant professor of Japanese at UNC Charlotte. “Fortunately, there’s so much more great writing by women in Japan. We’ve only scratched the surface.”

John Siciliano, the executive editor at Penguin Books and Penguin Classics who published Imamura’s 2021 psychological novel “The Woman in the Purple Skirt,” translated by Lucy North, said Japanese fiction is enjoying a publication boom reminiscent of Latin American authors in the 1960s and 1970s and Scandinavian writers in the early aughts.

“I think what’s really fueling this trend is the number of women writers, which is something we haven’t really seen much in Japanese literature,” said Siciliano, who will publish Emi Yagi’s “Diary of a Void,” translated by Boyd and North, and Seishu Hase’s “The Boy and the Dog,” both prize-winners in Japan, in 2022. “I think there’s a novelty factor to this boom in Japanese women writers and I think it plays off of how patriarchal the culture is, which makes it more subversive and exciting.”

Kawakami became a global sensation with “Breasts and Eggs,” a portrait of contemporary womanhood in Japan, winning awards and angering traditionalists in the process. She famously offered a feminist critique of Murakami’s novels during a 2017 interview.

In addition to an interest in reading Japanese women, Siciliano said literature from Japan is popular because it has a well-established tradition and is a perennial country of fascination. “It’s already got a reputation and a kind of cool factor,” said Siciliano.

Cool Japan can be traced back to the 1980s and 1990s, but the 2000s were transformative when it came to Japanese cultural exports. In 2002, revenue from sales of manga, video games, anime, J-pop, art, films and fashion totaled $12.5 billion — up 300 percent from 1992.

Designers such as Yohji Yamamoto and Comme des Garçons and films like Hayao Miyazaki’s “Spirited Away” — which won the 2003 Oscar for best animated feature — and Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation” from the same year, helped shape a new image of the country, which in turn led to publishers looking to Japan for fresh fiction.

While numerous titles have found success in the U.S., experts point out that translated works make up only around 3 percent of all published books in the U.S., and that the most frequently translated languages are still French, German and Spanish.

“I have a bunch of authors I follow with a passion and can’t wait to bring into English,” said Emily Balistrieri, who has translated nearly 30 Japanese titles to English, including Shaw Kuzki’s “Soul Lanterns,” published this year.

“Hopefully recent successes are also showing publishers that putting in the work on translations can pay off, because I know it has to do that for the business side to want to invest.”

Balistrieri, who is based in Tokyo, said Japanese readers consume a significant amount of literature by American authors. “I hope we can increase the number of Japanese lit geeks in the U.S. to match,” Balistrieri said.

Manga, comics or graphic novels originating from Japan, already has a massive readership stateside. In the first quarter of 2021, manga print book sales in America increased by 3.6 million units, year over year, according to research firm NPD Group.

The availability of Japanese anime on streaming platforms such as Netflix and Hulu and online fandom is helping drive its popularity.

Argabright, who covered “Breasts and Eggs” and Ogawa’s dystopian novel “The Memory Police,” translated by Stephen Snyder, during a podcast episode last year, hopes American readers will read across genres from Japan, from sci-fi to poetry.

“Japanese fiction is wider and more diverse than people think,” said Argabright. “A lot of people think Japanese translated works are kitschy, fun, lighthearted slice-of-life stories, but it’s way more than that.”