Jeffrey Chen spends his work hours sitting inside the closet-sized reception area of the Greater Chinatown Community Association in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where he works as program director.

The non-profit organization, which serves New York's Asian-American elders and students, is in a quieter, more affordable portion of the neighborhood, sandwiched between a florist and a closed down cupcake shop.

Chen said that his group is one of many social service organizations that are underfunded in New York’s Asian-American community, with only $10,000 of its $110,000 annual budget coming from government grants.

“Sure, as a collective, Asian Americans are doing well but if you separate it, a Laotian American is not doing as well as a Korean American.”

The association spends half its money on computer literacy and social programs for seniors and the other half for SAT classes, college application seminars, and financial literacy classes, Chen said.

“While it's nice to get this funding, it's definitely not enough for programming throughout the year, which I rely a lot upon donations and our own fundraising,” Chen told NBC News.

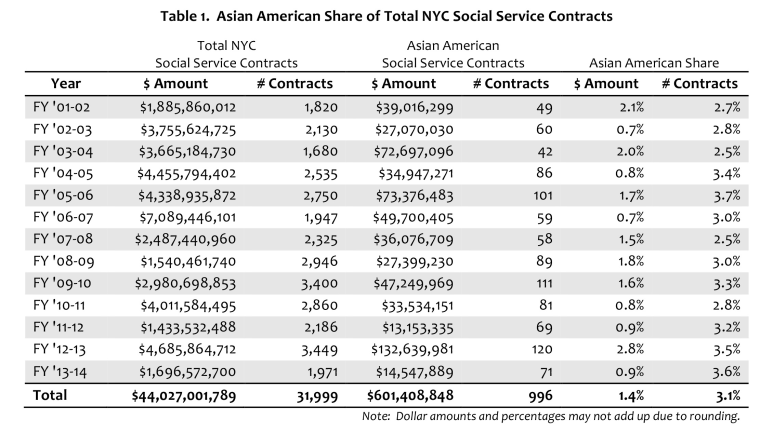

Lack of adequate government funding is an issue that affects many organizations in the Asian-American community. According to a 13-year analysis of New York City government grants released by the Asian American Federation in 2015, Asian-American community-serving organizations have only received $601 million out of the $44 billion granted in social service contracts in New York City, approximately 1.36 percent of total spending.

Meanwhile, New York’s Asian population has grown by 15 percent between 2010 and 2015 and now represents 13.5 percent of New York City’s population, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

Based on data collected from the Comptroller’s office, the Asian American Federation (AAF) report defined a program as serving the Asian-American community if either the contract awardee was an Asian-led community organization or the contract specifically focused on Asian Americans.

As the fastest growing racial group in the country, lack of funding for the Asian-American community is not unique to New York City. While Asian Americans have higher incomes on average than any other minority group, their wealth inequality gap is also one of the largest, according to a report released by the Center for American Progress.

“While it's nice to get this funding, it's definitely not enough for programming throughout the year, which I rely a lot upon donations and our own fundraising.”

Between 2010 and 2013, “the ratio between median wealth and wealth at the 20th percentile for whites was 12.8…lower than the comparable ratio of 14.3 for Asian Americans,” the report said.

Further disparities exist when it comes to which ethnic groups within the Asian-American community receive funding. More than 92 percent of funding in the New York Asian-American community goes to Chinese organizations according to the AAF report, catering to Cantonese and Mandarin speakers, a problem for non-Chinese speakers who also need services in their native language.

“Immigrants want to go to a nonprofit that has cultural and linguistic expertise in their own neighborhood,” said Jo-Ann Yoo, executive director of the AAF. “I don’t think it’s a coordinated or conscious effort to exclude any Asian groups, but it has to do with the way contracts are focused to serve the largest number possible.”

Yoo said that the Chinese community is the second largest immigrant community in New York City, so smaller communities are unable to compete with large Chinese nonprofits. Yet, even large Chinese organizations said they are underfunded.

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association stopped requesting funding from the government because the amount they received “was not worth the amount it cost to apply,” according to association secretary Wan Tam, who manages the organization's programs.

“It cost more money for the paperwork and people who understand how to do that paperwork, that it’s not worth it,” he said. “If it cost you over $20,000 to get $10,000 funding, what good is it? May as well ignore that and just do whatever we need to do so we’re not controlled [by the government].”

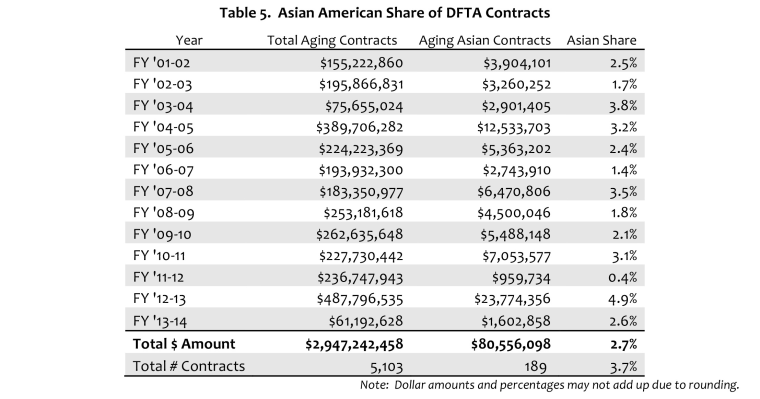

Tam said that it costs approximately $30,000 a month to operate his facilities and programs, which serves mostly senior citizens. He added that its mostly elderly people who need the social services but that there are not enough senior centers to serve the growing elderly population because of the lack of funding.

Asians and Asian Americans were the fastest growing segment of the senior population from 2000 to 2014, according to the AAF report, with growth of approximately 80 percent.

“The new immigrants that come over, the younger generation, work many years and are able to apply for their family, the older generation, to come here,” Tam said, adding that most older immigrants that come to reunite with their families do not speak English and have problems navigating New York City.

The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association tries to provide the elderly with practical needs to survive in New York City, mostly free of charge, Tam said. Some of the programming includes applying for a green card, learning how to pay utility bills, finding housing and food vouchers, and understanding the U.S. Postal Service. Volunteers and retirees do the training.

“We have to maintain our low labor cost and our labor is underpaid,” said Tam, noting that even full time staff, including himself, makes minimum wage. “It’s tough, for that amount of money most people don’t want to work [here] unless you’re a retiree.”

Even though the adult literacy classes charge a fee, Tam said that money solely goes to the teachers, who also earn minimum wage.

Chen of the Greater Chinatown Community Association said that his organization experiences similar struggles.

“We provide low-cost SAT classes for immigrant families and if we have more funding we could ideally eliminate the cost,” he said. “Because we still have to pay the teachers. Why teach for free when you can get paid $30-$40 an hour?”

A growing number of social service organizations in the Asian-American community are struggling to stay afloat and pay their workers a livable wage, according to Chen, who attributes part of the problem to the model minority myth. Even the Chinese-American Planning Council, one of the largest social service organizations in the country, also said it is severely underfunded.

“All non-profits face the issue of fundraising and planning,” Steven Yip, the director of operations at the Chinese-American Planning Council, told NBC News. “For example, day care teachers will stop working at NGOs when they can go teach at a school and get paid much more. NGOs have to bring in other sources of funding to augment programs and salaries.”

“I don’t think it’s a coordinated or conscious effort to exclude any Asian groups, but it has to do with the way contracts are focused to serve the largest number possible.”

Yip added that the government often uses superficial means to determine the amount of funding to grant, such as cutting off daycare funding based on zip codes.

“In general the government refuses to recognize the circumstances of nonprofits are in,” he said.

The office of New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio told NBC News that, while they cannot legally give preference to certain groups over others, contracts with the city require that organizations provide services to anyone seeking them.

"The administration has also taken concrete steps to promote equity and community-based program design as well as increasing access and community outreach," Ryan Murray, a spokesperson for the New York City Mayor's Office of Contract Services, told NBC News. "We are consistently working to ensure cultural competency and language proficiency and are always seeking to expand the pool of providers who do business with the city by making contracting easier."

"Finally, we also offer a variety programs and services and conduct extensive outreach to help increase the number of minority and women-owned businesses that contract with the City of New York, including those that are Asian-led and -owned," he added.

Chen said that part of the problem is that the government thinks that the Asian-American community does not need as much assistance as other minority groups because there are many Asian-Americans that are very well off. But some, he argued, some slip through the cracks.

“I would argue that a lot of Southeast Asians who come from being displaced by war and things like that suffer even more because in the politics of the Asian-American community there is always a push for aggregating the information,” Chen said. “Sure, as a collective, Asian-Americans are doing well but if you separate it, a Laotian American is not doing as well as a Korean American."

Yip, of the Chinese-American Planning Council, said that one of the biggest challenge is to diversify funding sources and identify individual donors.

“The problem is that other communities don’t know about us so we can’t get grants and funding,” he said.

Although many social service organizations continue to struggle in finding funding, Yoo of the Asian American Federation feels optimistic and said that she has already begun to see changes.

“The city is getting much better, and they’re restructuring to include language and cultural expertise credit in the [request for proposal] point system for awarding contracts,” she said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.