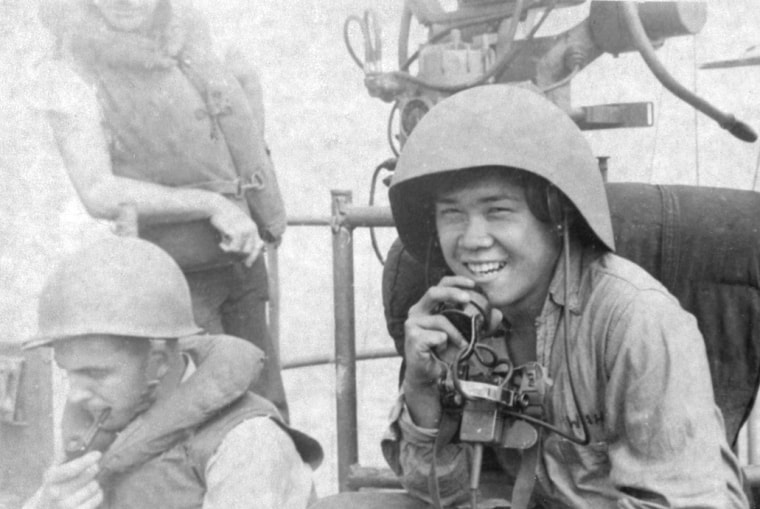

During the height of World War II, U.S. sailor Austin Wah helped sweep for naval mines on a converted destroyer in the waters off Okinawa, an island group that belongs to Japan.

It was dangerous work.

Once, Wah, now 94, sounded the alarm as a kamikaze pilot tried to kill him and his shipmates by directing his plane into their boat. Fortunately, the wing clipped the water first, flipping his aircraft into the sea.

"If that had hit our ship, I wouldn't be here," Wah, who lives in a retirement community in Maryland, told NBC Asian America.

Wah is among the more than 18,000 Chinese Americans who served in World War II when the Chinese Exclusion Act still prohibited most Chinese immigrants from becoming naturalized citizens.

In 2018, they were collectively honored with a Congressional Gold Medal, joining other World War II vets like the Japanese American Nisei soldiers and Filipino and Filipino Americans who have already had their contributions recognized with the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the nation's highest civilian honors.

But Chinese Americans who served in World War II and their family members will have to wait a little longer for the medal to be formally unveiled. An award ceremony at the U.S. Capitol originally planned for late April has been postponed because of COVID-19.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

A spokesperson for House Speaker Nancy Pelosi's office said organizers hope to reschedule the event for later this year.

Ed Gor, national director of the Chinese American WWII Veterans Recognition Project, said the fewer than 300 service members still alive today are eager to see the medal presented.

"Most of them came back to become professionals, businessmen, getting married, starting families, just contributing — I'd call it almost silently — into the fabric of the United States of America," Gor said. "These guys had never been acknowledged for their service."

Wah, who was born and raised in Baltimore, was 18 when he got his draft letter in 1943. Wah, one of eight children, was placed in the Navy because of a manpower shortage, he said. His brother ended up in the Army Air Forces.

After boot camp, Wah was assigned to a position that handled damage control for ships, he said. Later, he was sent to Treasure Island, near San Francisco, for advanced welding.

Wah said that while he was the only Chinese American in his group of mostly older men, he didn't experience discrimination like others had.

"They treated me like a younger brother," Wah said.

Wah's mettle was put to the test on the line of battle in the Pacific. In addition to surviving a kamikaze attack, he cheated death once more when his ship got caught in a powerful typhoon just three days after the Battle of Okinawa.

"One minute you're way down, you see water all around you," Wah recalled. "Next thing, you're way up top, you look down, and the water is all below. And then you see a lot of people floating by, because there's no way you could rescue them."

After the war ended, Wah rode his ship back to the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York, where it was decommissioned. He never forgot the feeling he had when they passed by the Statue of Liberty.

"It makes you proud that you did something," Wah said. "It hits you just like that."

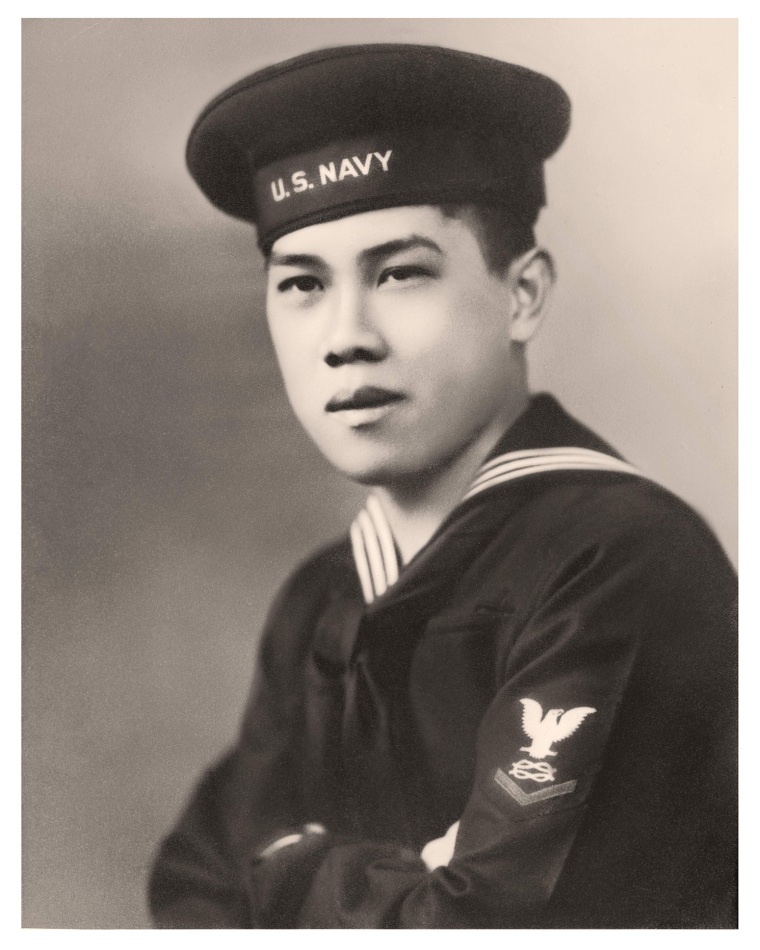

Unlike Wah, Robert M. Lee began his journey into the U.S. armed services in China, where he was born.

Lee said his family had papers allowing them to immigrate to the U.S., thanks to his mother's relatives who had lived in the U.S. around the time of the Gold Rush. But Japan's attack on China in 1937 stalled their plans, forcing the family to flee to the city of Kunming.

Unable to find work or go to school, Lee visited a nearby U.S. air base to see whether he could enlist. He was around 14 at the time, and no one asked to see his birth certificate, even though he had one.

"People laughed at me, but they were very helpful," Lee, 89, recalled.

Lee enlisted as a private into the 14th Air Force of the U.S. Army Air Corps, formerly known as the Flying Tigers. The small company of air fighters had a reputation for their derring-do and ability to outmatch Japan’s much larger air force.

Lee ended up with the Army Corps of Engineers. In 1945, he was transferred to work on Ledo Road, later renamed Stilwell Road, a strategic military route that ran from northeastern India through Myanmar to China.

After his Army discharge following the war, Lee remained in India for seven years, helping to build hydroelectric dams. He also later joined the U.S. Foreign Service.

Lee said it was only a couple of years ago that he learned of efforts to award a Congressional Gold Medal to Chinese American World War II vets.

"I was elated on my behalf, of course, but very disappointed that it was so late that many people would not live long enough to receive it," he said.

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Wah, who followed in his father's footsteps by going into the laundry and dry-cleaning business, said serving his country was simply his duty.

"I always just thought I was one of the guys," he said.

Lee, who retired in the '90s from a computer center job with the Senate and today lives in Arlington, Virginia, went on to serve twice as president of the 14th Air Force Association before it disbanded in the late 2000s.

Lee said he sees America's battle to contain COVID-19 as an even bigger challenge than what the nation and its allies faced during World War II.

"I think this is much worse, because we don't know what's going to happen next, and we cannot fight it," he said.

Both men participated in a smaller ceremony in Washington, D.C., in early 2019. Both were planning to attend the one in April, as well.

Gor hopes the April event can take place this fall, especially because fewer than 300 servicemen and women remain of the more than 18,000 who answered the call to duty.

"I'm never going to say that any one of our men and women who served were any more brave or courageous or patriotic next to anyone else who was African American or Hispanic or white," he said.

"What we'd like everybody to know is we served alongside everyone else for the betterment of the country — and to win this war," Gor said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.