In April 2009, Elizabeth OuYang discovered a lump on her breast in the shower and was instantly reminded of her mother, who battled breast cancer silently. Anxiety flooded her mind as she tried to piece things together.

“I went to the doctor’s and they confirmed I had breast cancer," OuYang, a civil rights attorney, told NBC News. "I constantly was thinking about my mom and whether I was going to have my mom’s fate…I really thought I was going to die like my mom.”

OuYang said she didn't want to battle the disease behind closed doors, but finding Asian-American women she could talk to was a herculean task.

“It took me the longest time to realize that talking about breast cancer doesn’t define me. What I’ve done is what defines me."

Her family had referred her to Caucasian women who shed insight on what it was like to get chemotherapy for the first time, or what it was like to enroll in a laughing class to relieve some of the stress in between treatments. As much as OuYang appreciated their honest advice, she yearned to speak and connect with other Asian-American women.

“I really wanted to speak to other Asian-American women who also had breast cancer in part because there are certain cultural similarities and would understand some of my fears and thoughts in decisions I would have to make,” OuYang, who has been cancer-free since October 2009, said.

She perused the aisles of many bookstores in Boston and New York, but was frustrated when she couldn’t find many books on how to deal with breast cancer as an Asian-American woman.

Now, six years after her diagnosis, OuYang has launched Plum Blossoms, a blog for Asian-American women who have been diagnosed with breast cancer to tell their stories. “Plum Blossoms was started because there needs to be an avenue for Asian women with breast cancer who want to express their fears, ambitions, and experiences in a safe manner that respects family harmony and empowers Asian-American women living with breast cancer," she said.

OuYang initially began the project with the hopes of launching a book, but decided that a blog would give people the opportunity to feel more comfortable about sending anonymous submissions.

OuYang traveled to California and Boston, recording oral histories and connecting with Asian-American women who shared their triumphs, their weaknesses, and their fears during their journey. She also reached out to the Asian Pacific Islander American Health Forum in California and the APA Institute at New York University to find Asian-American women with breast cancer who were willing to share their stories on her blog. Two of the women she has interviewed include Linda I, a Japanese American astrologer and Mai Tran, a refugee from Vietnam.

The title of the blog represents the number of Asian-American women affected by breast cancer, juxtaposed with the symbol of the plum blossom, “an Asian flower that can grow in the winter and survive four seasons.” For OuYang, the plum blossom represents the strength and determination of Asian-American women and is dedicated to her mother, who battled cancer silently, and to one of her friends, "whose public battle with breast cancer challenged cultural norms."

A Growing Trend

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, breast cancer is the second leading cause of death from cancer among white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander (API), and American Indian/Alaska Native women. Chien-Chi Huang, executive director at Asian Women for Health and founder of the Asian Breast Cancer Project, told NBC News she is concerned about the lack of resources and cancer education dedicated to the API community.

“A lot of the women are still suffering in silence because the prevention concept is not very prevalent in our community,” Huang said, adding that there is a lot more work that needs to be done in terms of community education and pushing the medical community “to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate and relevant information for our community.”

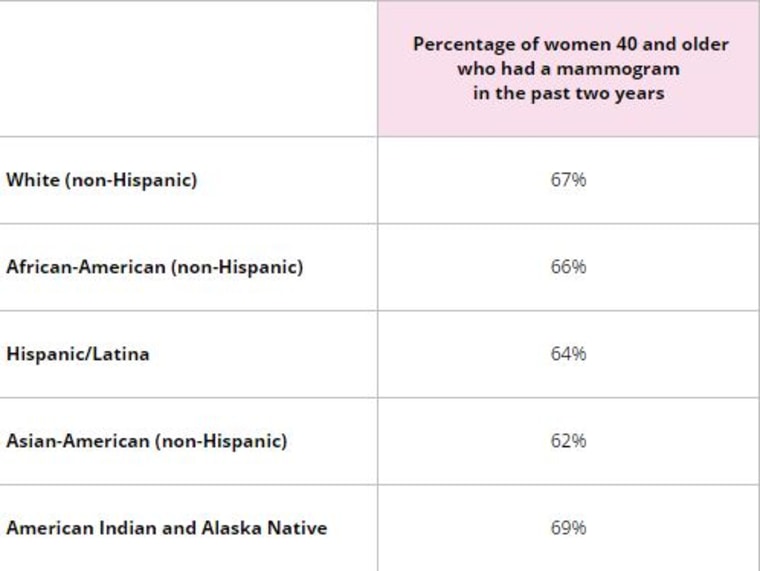

According to the Asian Breast Cancer Project, API women have low rates of breast cancer screening, “which increases their chances of later stage disease prevention.” The report also points out that immigrant API women living in the U.S. for 10 years have an “80% higher risk of developing breast cancer than their newly-arrived API immigrant counterparts.”

Huang added, “As a consequence, I think there are still many Asian women who don’t realize that they can be at risk for breast cancer and we’ve found that there’s a trend that more and more younger Asian women are diagnosed with breast cancer.”

She said she is also concerned about the American Cancer Society’s new guidelines which recommends women should plan on getting mammograms at age 45 as opposed to 40.

Huang believes the screenings should occur as early as possible. “When I was diagnosed, I was just 40 years old. I did a lot of research and to my surprise, I learned that the rate for breast cancer for Asian Americans is increasing while it’s decreasing for all other populations," she said.

"You can choose to deal with it silently, but I want them to know the benefits of sharing and that there is support out there.”

But some Asian-American women often keep the diagnosis to themselves, Huang said, because they don’t want to be viewed as a “burden" to their families.

“Some people still have this idea that cancer is a curse, it’s something that you did bad in your past life. People don’t want to talk about it or let others know they had cancer,” she said.

Huang explained that the concept of prevention is not prevalent in the API community because many often delay treatment until they get sick, or the hospital is viewed as a place to get treated only when you have a sickness present.

“People don’t feel the need to utilize preventive care,” she said.

Roxanna Bautista, senior director of engagement strategy at the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, says it is crucial for API women to get screened as early as possible.

“We need to continue to educate women to get screening early and we need to educate around what may be the causes of cancer and how there can be behavioral things to do to try to reduce chances of it,” Bautista told NBC News.

Bautista also cites cultural, language, and educational challenges as barriers that might prevent API women from getting screened. There is also a level of shame that might exist when showing a “body part to a physician” or conducting a self-breast exam.

OuYang added that, especially in the Asian-American community, women often deal with issues in a private manner, as opposed to disclosing health issues with family and friends.

“They’re battling it silently because our cultures have taught us to look to our families for strength and not outsiders. Our cultures teach us to share joys, but not sorrows. I think for a long time, people viewed cancer as an embarrassment or a form of embarrassment,” OuYang said.

Particularly for Asian-American women, she said, the family unit is highly regarded and one’s own health is often put off in order to tend to children and elders. “For those of us whose mothers have had breast cancers, uniformly many will say that their mothers dealt with it quietly. They were stoic, they were courageous, but they didn’t reach out to family for help," she said.

'Breast Cancer Doesn't Define Me'

Born in Rochester, New York, OuYang is the daughter of immigrant parents from Foshan and Shanghai, China. Her father was a doctor and her mother was a housewife who raised six children.

OuYang began her decades-long career as a civil rights attorney after attending a “Women in Law” conference during her undergraduate years at the University of Michigan. It was there that she was introduced to a community lawyer from Boston who agreed to let her shadow her. She later worked for the Disability Law Center in Boston for three years, where she represented persons with disabilities and worked on public housing discrimination cases.

After her mom passed away from breast cancer in 1991, OuYang moved to New York City, where she worked at the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund for eight years and represented Asian Americans who were victims of hate crimes and police brutality. She also conducted pro-bono legal advice clinics for communities that may have been affected by post-9/11 government policies.

For a long time, OuYang didn’t want breast cancer to define her life or take precedence over her career, so she kept her stage 1 diagnosis a secret until she felt comfortable disclosing it to her employers and close family and friends.

“I want them to feel like they can laugh and let it out. If they can cry, they can cry."

“You really feel isolated and you feel like you don’t want to be branded or people to feel sorry for you and you want to be known for who you are,” OuYang said. “It took me the longest time to realize that talking about breast cancer doesn’t define me. What I’ve done is what defines me."

During her journey, OuYang went through periods of denial, grief, and acceptance. She underwent chemotherapy, had a mastectomy, and lost her hair. But one of the things that really helped her find peace was a book her friend had given her that inspired her to make a list of things she wanted to accomplish.

“I wrote down eight things and that gave me so much hope because I looked forward to it. I did all eight things, one of which was a trip to Greece," she recalled, a trip she eventually crossed off her bucket list.

'There is Support Out There'

OuYang said she hopes her blog will be a place where people can feel welcomed, and a place that will bring comfort to questions that might keep women up at night — questions like, "Am I going to die?" or "Can I fight this?" and "How much longer do I have?"

“I want them to feel like they can laugh and let it out. If they can cry, they can cry. I really hope my blog will be there for all women, but particularly women who were recently diagnosed," she said.

OuYang wants to see Plum Blossoms expand and reach out to potential donors and funders in the near future so she can translate the interviews in different languages. She cites a conversation with a woman struggling to find stories of Asian women like her as her inspiration to grow the blog.

“She went to a Chinese site after she was diagnosed and got discouraged because it wasn’t a blog," OuYang said. "It was stories of famous Chinese women who got breast cancer.”

But when OuYang showed her own blog to the woman, the woman was pleased to find that the stories on the blog featured the photos of everyday Asian-American women, not just celebrities. It helped her find comfort in her own journey as a woman navigating through a recent breast cancer diagnosis.

“Even though she couldn’t read English, she saw the pictures [on my blog] and she was so happy," OuYang said.

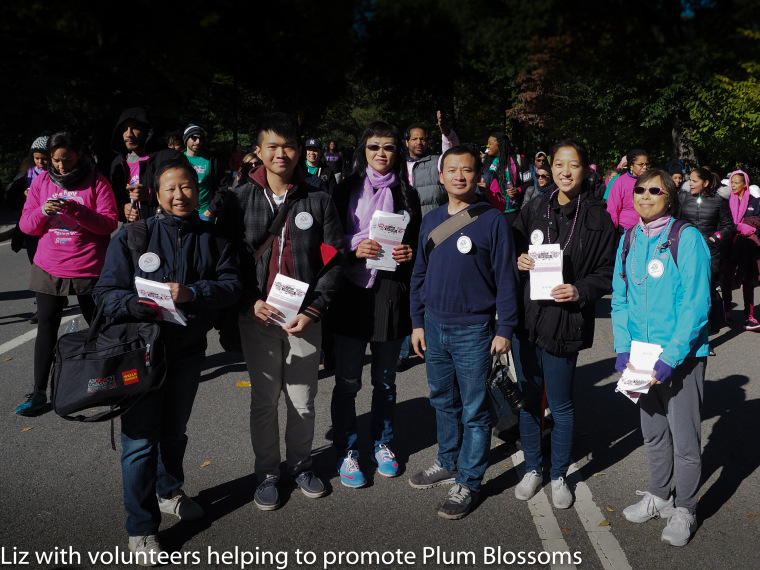

Earlier this month, OuYang, along with some of the women who have volunteered and submitted stories to Plum Blossoms, marched in the Making Strides Against Breast Cancer Walk in New York's Central Park.

OuYang hasn’t missed a single march since her mom was diagnosed with breast cancer. She will continue to march for the years to come, she said — for Asian-American women who are both silently battling cancer and for those who have publicly shared their stories.

“I want to make it easier for other Asian-American women," OuYang said. "You can choose to deal with it silently, but I want them to know the benefits of sharing and that there is support out there.”