It was 5 a.m. Feb. 1 in Yangon, Myanmar, and Juna Ko Ko’s mother couldn’t sleep. Rumors of a military coup had been circulating all week. A few hours later, the internet shut down.

Ko Ko had been texting his mom that afternoon from his apartment in Tampa, Florida, when the news came through. Hours before Myanmar’s Parliament was set to convene and swear in the elected officials from the November 2020 election, the military had detained leaders from the National League for Democracy (NLD). This included President Win Myint and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.

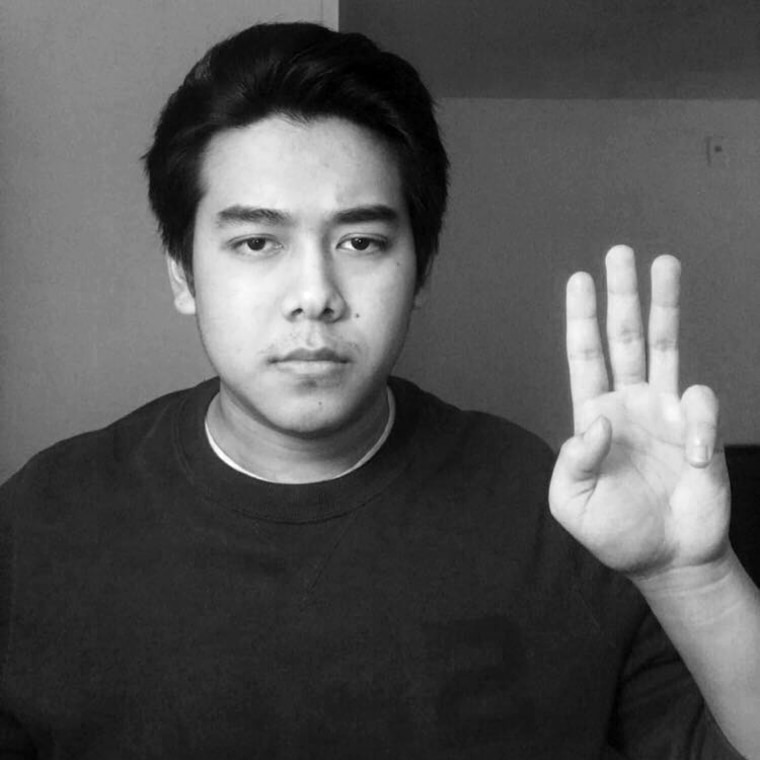

“For me to be talking to my mom, and to have it cut off just like that … it’s a very intense feeling to be so helpless,” said the 22-year-old, who came to the United States for college.

But despite the distance, Myanmarese communities in the U.S. have joined the worldwide civil disobedience movement to protest the military coup in the Southeast Asian nation. From the United Nations headquarters in New York to the U.N. Plaza in San Francisco to the streets of Washington, D.C., and soon, Orlando, thousands of Myanmarese Americans have protested the government takeover in the past two weeks. They’re urging international peace organizations to demand the release of the NLD leaders and urging the military to recognize the results of the 2020 general election and restore the civilian government.

The NLD has held a majority since 2015, which was seen as a sign of progress toward a more democratic government in Myanmar, and had once again achieved a landslide win of parliamentary seats in the 2020 election. Despite this, the military alleged voter fraud and declared a yearlong state of emergency.

For many younger Myanmarese like Ko Ko, this was their first time joining the fight for democracy. Members of the 88 Generation — Burmese student protesters who had participated in a pro-democracy movement in 1988 — had stood up for the Burmese people time and time again. (Burma was the former name of Myanmar until 1989.) During the Saffron Revolution, caused by the military’s removal of fuel subsidies in 2007, they had joined students and Buddhist monks to protest peacefully. ”That’s what makes it so heartbreaking—because there’s so much progress being returned,” Ko Ko said.

Despite the setbacks, many activists are still hopeful that this time, things will be different. “You’ve messed with the wrong generation,” posters read. “We’ve been advised by the generations of the past to prevent confrontation,” Ko Ko said. “And then we applied something that they hadn’t really incorporated, which was social media.”

During the first few days of the coup, the military had shut down the country’s internet and blocked several social media sites. But with virtual private networks and SIM cards from Thailand that work on foreign telecoms, tech-savvy Myanmarese managed to flood their Facebook, Instagram and Twitter timelines with footage from protests inside the nation, memes and hashtags to communicate their fight to the rest of the world.

“What the international students, or people my age are doing right now is funneling information on what’s happening in Myanmar to raise awareness about the atrocities that are happening in Myanmar,” Ko Ko said.

The internet was restored Feb. 7, and the military itself had recognized the power of social media and tried to use it to justify the coup. On Thursday, Facebook announced that it would reduce the distribution of content and profiles run by the military in an attempt to limit the spread of misinformation. It also will suspend Myanmar government agencies from sending content-removal requests to Facebook through normal channels in order to protect the free speech of the Myanmarese online.

Okkar Min Maung, 35, an actor and model from Yangon who now lives in New York City, has posted frequently to share protest information and news inside Myanmar with his over 280,000 Facebook followers. A newly created civil disobedience movement page has over 244,000 followers as of Feb. 11.

“There is a new generation that's much more confident than before,” said Magnus Fiskesjö, an associate professor of anthropology at Cornell University. “They are connected to everyone else [in the world] in a way that didn't happen before.”

They also have the support of the 88 Generation. For older Myanmarese, the military takeover was yet another painful reminder of their country’s struggle to achieve democracy. More than 30 years later, they have sprung into action against the military government again.

Khin Maw, 67, an activist who had been jailed for his participation in student demonstrations during his youth in Myanmar, attended a protest at the Myanmar Consulate in Los Angeles last week. He had last visited Myanmar in 2019, and had seen the progress of free speech and free elections. “The country was changing a lot, I was so happy,” he said.

In America, Myanmarese immigrants have used their tightknit national network to garner support for the civil disobedience movement. Ko Ko Lay, a spokesperson for the Free Burma Action Committee—San Francisco chapter, has been involved in the Myanmarese American community since immigrating to the U.S. in 1992. “Today, after the military took power, we have only two groups: a small group of the military regime, who have all the power, and the rest are the people of Burma. Our fight is very clear,” he said.

When he was 27, Ko Lay served as secretary of information for the central executive committee of the All Burma Students’ Democratic Front, an armed student group founded in response to the 1988 uprising. Now, he is working to get international aid for Myanmar.

On Feb. 9, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously passed a resolution introduced by the Free Burma Action Committee, condemning the coup and supporting a peaceful transition to democracy in Myanmar. Italso called on the White House to take action against the military government.

The widespread support from Myanmarese Americans is exactly what their community wants to show the world, Khin Maw said. “If I have a voice to our people back there: We stand with you all the time. We, the people from outside of the country, we are with you, we’ll help you always. And be brave.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.