San Francisco District Attorney Brooke Jenkins said her office will review a number of high-profile anti-Asian attacks for any evidence to support hate crime charges.

“We shouldn’t be selective about which laws we choose to enforce,” Jenkins, an experienced prosecutor and critic of ousted predecessor Chesa Boudin, told NBC Asian America. “Particularly, the hate crimes laws, which were developed in this country to protect certain vulnerable communities.”

Charles Jung, a trial lawyer and executive director of the California Asian Pacific American Bar Association, said Jenkins’ decision to reexamine criminal cases involving Asian victims shows that she’s prioritizing the safety concerns of the community.

“I’m optimistic that she’s bringing a new perspective to the issue of how to address intergroup violence and fight Asian hate,” Jung said, speaking in a personal capacity, noting Jenkins’ willingness to devote additional resources to a hate crimes unit and to actively engage with Asian American leaders.

Jenkins, who last month became the first Latina to hold the office, said her office will begin by examining the dozen criminal cases reviewed by the San Francisco Standard and KQED in a June article. Although all 12 cases were initially investigated as hate crimes, only two were ultimately charged as such.

Jenkins has tapped Nancy Tung, a veteran Bay Area prosecutor who ran for district attorney in 2019, to lead the investigation.

Legal experts say hate crimes are extremely difficult to prosecute, largely because proof of motive is hard to come by. Jenkins said her office plans to gather evidence by analyzing video footage and defendants’ online communications.

“We know generally that when someone utters a slur at the time of the assault, it makes their animus very clear,” she said. “We also want to look at someone’s social media and text message history.”

One case Jenkins singled out involves a Chinese immigrant who was assaulted while collecting recyclable cans for money. Boudin’s office charged the man who was directly involved in the attack but declined to pursue charges against another man who recorded the incident, even though both men had used hateful language that’s caught on video. Given the recorded evidence, Jenkins said, the DA’s office could potentially have pursued hate crime charges.

A hate crime enhancement can add up to three years of prison time to any other sentence a defendant receives for an underlying felony, which Jenkins said is a “relatively minor” change in the legal system.

“We’re not talking about something that’s catastrophically changing the legal landscape but it means a whole lot to victims,” she said.

Shirin Sinnar, a Stanford Law School professor and legal scholar who has extensively researched hate crime laws, said there’s little evidence showing that increasing sentences with hate crime convictions actually deters others from committing such crimes.

“Typically, if someone commits a hate crime they’re also committing another assault,” she said. “To say they’re deterred by a marginal increase in prison time is not a realistic assumption.”

At the same time, Sinnar said, hate crime prosecutions have historically carried tremendous symbolic value to victims and their families.

“Having targeted crimes acknowledged by the state in some way — to have public officials stand with the victims and the community — is extremely important,” she said, “but doesn’t have to take the specific form of increasing criminal sentences.”

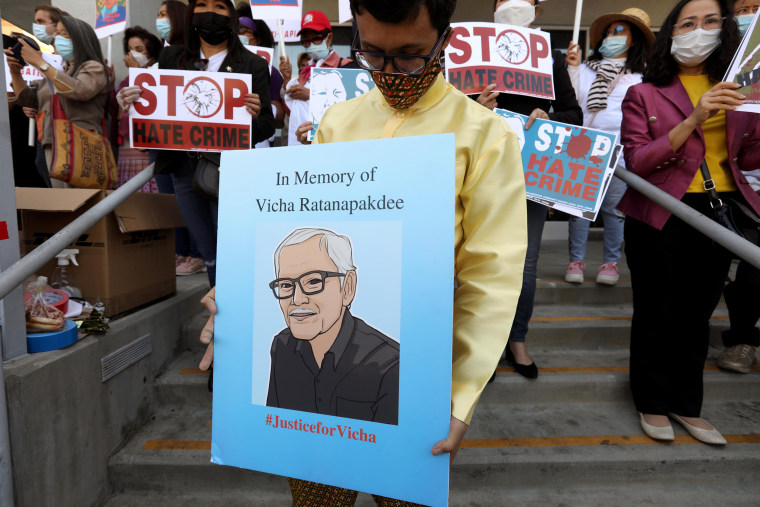

Boudin, who campaigned on ending cash bail and reducing jail and prison populations, had a fraught relationship with Asian American voters, many of whom support tough-on-crime tactics to address public safety. He also came under fire for calling the murder of Vicha Ratanapakdee, an 84-year-old Thai immigrant, the result of a “temper tantrum” and declining to pursue hate crime charges against the suspect, Antoine Watson. (Boudin has said the comment was taken out of context and that he didn’t believe Watson’s conduct was “excusable.”) Two-thirds of Asian voters backed Boudin’s recall in June, the highest level of all racial groups, according to a poll conducted by the San Francisco Standard in May.

Jenkins, who worked in the DA’s office for seven years as a prosecutor, resigned last October after criticizing what she saw as Boudin’s failure to prosecute serious crimes, and later became a leading supporter of his recall.

In an email statement to NBC News, Boudin said Jenkins’ plan to reinvestigate criminal cases is “deeply disappointing” and misinformed.

“Playing politics with charging decisions made by veteran prosecutors based on the law and the evidence gathered by police is a ruse and it will not make the city safer,” he said.

Some community advocates agree.

“These cases were already thoroughly vetted and, in many instances, a preliminary hearing before a judge was conducted,” said Angela Chan, a civil rights lawyer and the chief of policy at the San Francisco Public Defender's Office, an agency that’s representing some of the defendants in cases Jenkins is eyeing for review. “There’s no evidence to support hate crime enhancement.”

Hate crime and gang enhancement laws disproportionately impact Black and brown people, Chan continued, not because they commit such crimes at higher rates but because they’re more aggressively targeted.

“Even if these laws don’t result in more prosecutions and convictions,” she said, “they’ll result in more funding to police, which comes at a cost to funding for evidence based prevention programs and community investments that get at the root of the issues.”