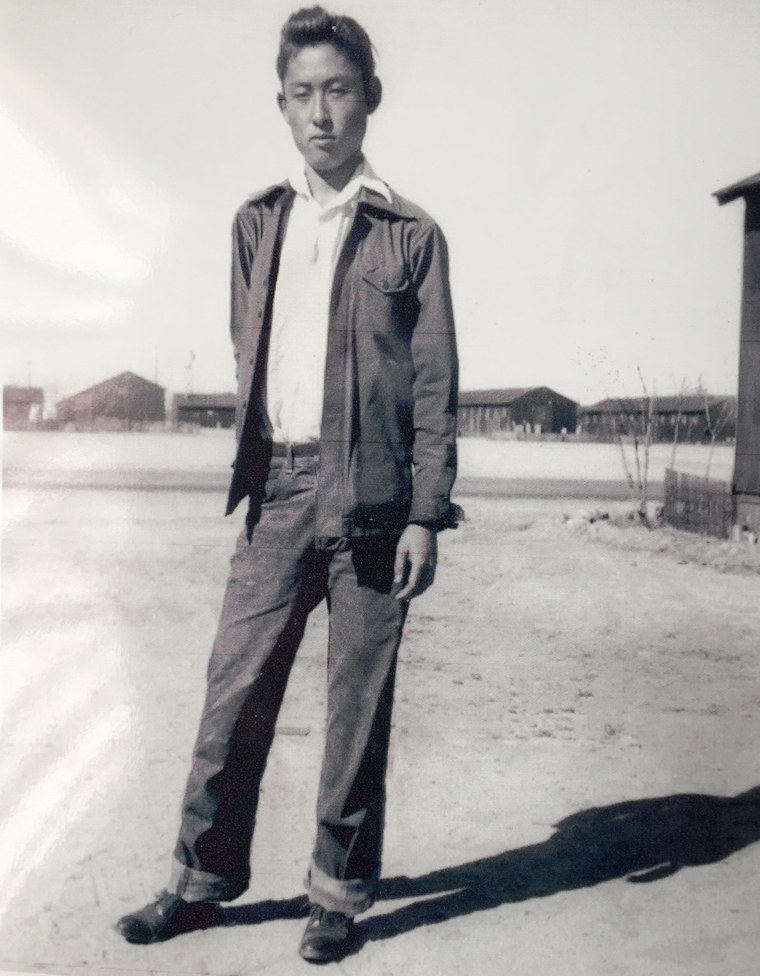

It's taken a lifetime for Hank Umemoto to make peace with what happened more than 70 years ago.

Umemoto was 13 when he and his family were taken away from their vineyard in Florin, Calif. His father died in 1931, when Umemoto was two, and his mother and older brother were left to take on the brunt of the farmwork.

Six of them boarded the train to Mojave, Calif. and took a bus into Owens Valley. It was May 25, 1942, and their final destination would be Manzanar where Umemoto would share a room with his mother Kusu and his sister Edith on one side, and his brother Ben, sister-in-law Annie, and their son Ronny on the other.

“All of a sudden we saw this barbed wire fence,” Umemoto, 87 and now retired and living in Gardena, Calif., told NBC News. “That was the first time I felt criminalized. All of a sudden your life has changed.”

Early the next morning, he was sitting with a friend when two saw guards drove by. Umemoto extended a middle finger and shouted, “F— you!”

The guards stopped. The next thing Umemoto knew, he was staring down a gun barrel.

“What did you say?” the soldier asked.

But Umemoto was speechless. “I was just ashamed that I couldn’t say anything,” he recalled.

Lingering Stigma

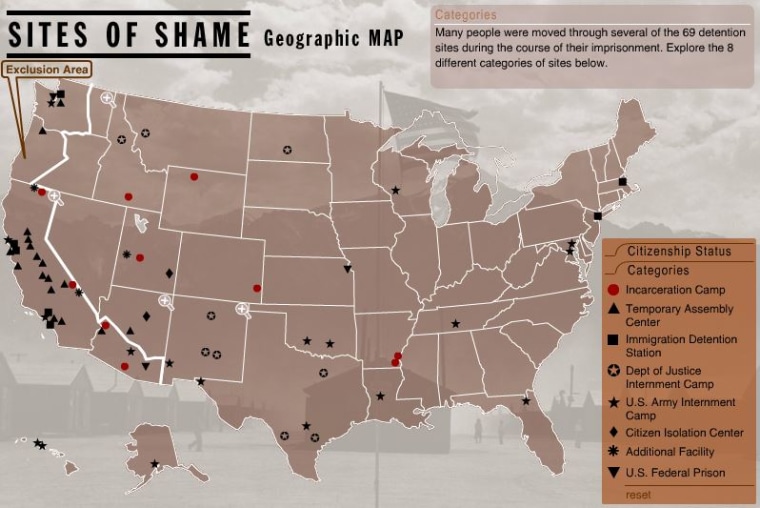

From 1942 to 1945, Umemoto was one of thousands who lived at Manzanar, a collection of wooden barracks surrounded by barbed wire fences and armed guards located at the foot of the eastern Sierra Nevada mountains in California’s remote Owens Valley. In the months following the Pearl Harbor attack of Dec. 7, 1941, more than 110,000 Japanese Americans were forced to leave their homes and businesses and relocate to one of 10 camps scattered across the West.

Although it has been 70 years since the end of World War II, the camps still leave their mark on the survivors of incarceration, who say it’s as vital as ever to learn from the past and essential that people across the country are educated about this chapter of American history.

“It’s what the camp represented that was harmful,” Umemoto said. “It made us feel inferior, like we weren’t patriotic. There were some times when I wished I wasn’t Japanese.”

After the war, Umemoto carried that same sense of shame. He left Manzanar on Aug. 6, 1945, with his mother and his sister. They went to live in a 9-foot by 12-foot room in a hotel owned by a family friend on the edge of Los Angeles' Skid Row. He was haunted by the images of U.S. wartime propaganda depicting the Japanese as cartoonish figures with slanted eyes and speaking broken English.

By his first day at Roosevelt High School, he could already feel he was different.

“We were saying the Pledge of Allegiance and I couldn’t,” Umemoto said. “I just stood there with my hands by my side. Kids were giving me dirty looks but how could I stand there and put my hand over my heart for the country that really [messed] me up?”

After graduating high school, Umemoto enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in Tokyo and preparing to be deployed to fight in the Korean War when he learned he had a chance to become an interpreter.

But he failed the Japanese language interpreter test. A friend managed to pull some strings and helped him stay in Tokyo for the next year and a half before he was sent home. He served six more years in the Army Reserve before being honorably discharged.

“After I got home I continued civilian life. I started gardening. I knew these people who had a nursery. In those days, Japanese were gardeners. And I went to night school at Los Angeles City College,” Umemoto said.

He attended Cal State Los Angeles from 1954-1955, intending to graduate, but the shadow of Manzanar loomed over him.

“We had some required courses we needed to graduate,” Umemoto said. “One of them was speech. I was embarrassed to be Japanese. I’m a Nisei [second generation] so I have an accent. I could see myself standing up there speaking broken English, a Jap.”

Speaking Out

“We really were in a concentration camp. We were imprisoned."

For decades after the war, the legacy left by Manzanar and the other nine camps was left unacknowledged, but slowly, former incarcerees began to share their stories.

In 1973, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, who was sent to Manzanar at the age of seven, published “Farewell to Manzanar,” which brought the stories of incarceration to a national stage. The made-for-TV film adaptation of Houston’s memoir “was the first commercial film written, performed, photographed and scored by Japanese Americans about the World War II camp experience,” according to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

“We never talked about it, or if we did it was just joking,” Houston, 81, told NBC News. “I was married 13 or 14 years before my husband knew [about Manzanar]. Somehow he asked me about it. I began to tell him and I became hysterical. It was shameful for three years to be living in this prison camp.”

Joyce Okazaki, 81, echoes Houston’s memories of Manzanar. “We really were in a concentration camp,” Okazaki told NBC News. “We were imprisoned. We didn't have due process. We should be aware of our freedoms and make sure they are honored. Don't send people to prison just because of how they look.”

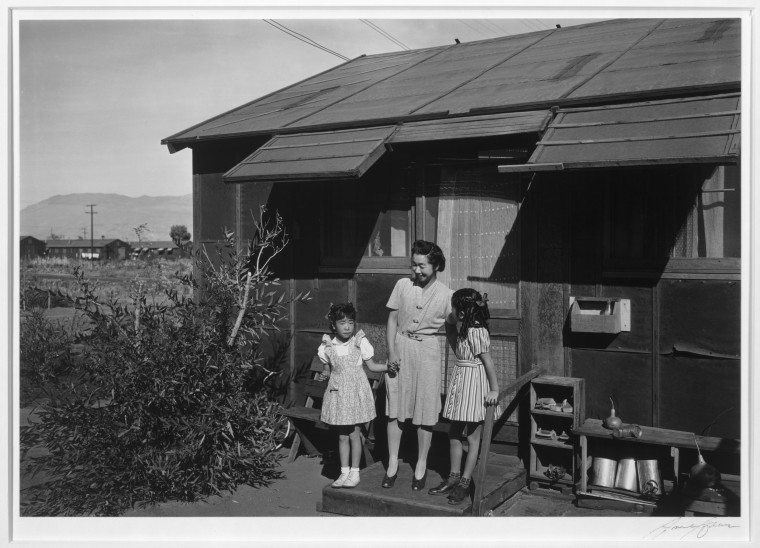

Okazaki, then called Joyce Nakamura, was seven years old when she and her family were forced to move from Los Angeles to Manzanar in 1942. She doesn't remember much other than going to classes and playing with her friends.

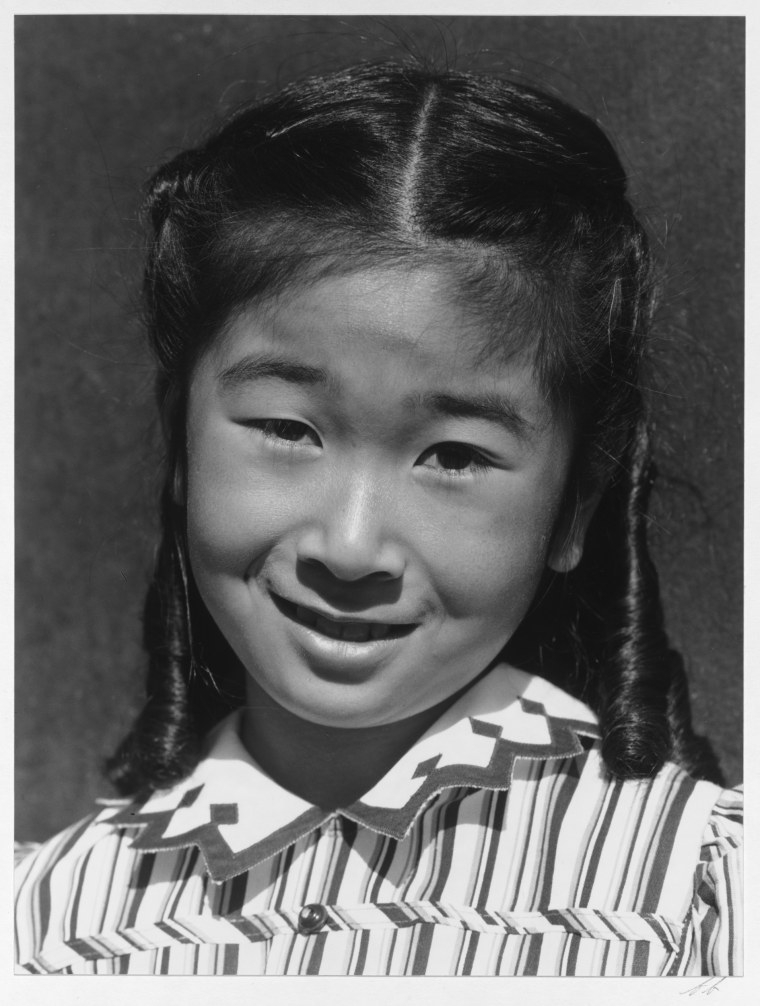

The most significant event, Okazaki said, was being photographed by famous photographer Ansel Adams in 1943. Okazaki recalled she was impatient for most of the day, and she didn't like her dress. She said she argued with Adams because he wouldn't let her look into the camera.

Adams’s photos from Manzanar, featuring Okazaki, her sister, and her mother, were published in 1944 in his book “Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese Americans.” Twenty years later, the book was republished with Okazaki’s photo on the cover.

Okazaki, a third generation American, said that while she was largely shielded from negative experiences in the camp and from racial discrimination after leaving Manzanar — she and her family were released in 1944 after swearing a loyalty oath, and they moved to Chicago — the experience has inspired her to share her family’s story with anyone who will listen.

“It's just frustrating to me that there are textbooks that don't even cover [incarceration] or maybe they have a few sentences,” Okazaki, who now resides in Seal Beach, Calif., said. “It's really a shame…There are still some people who don't want to talk about it. My sister doesn't want to talk. She relies on me to tell our story.”

A History of Discrimination

These days, Manzanar is one of two camps officially designated a National Historic Site.

“It’s what the camp represented that was harmful. It made us feel inferior, like we weren’t patriotic. There were some times when I wished I wasn't Japanese.”

Lily Anne Yumi Welty Tamai, curator of history at the Japanese American National Museum, told NBC News she hopes people draw from the history of incarceration to reflect on the consequences of using power to displace others.

“Our nation’s diversity is really our strength,” Tamai said. “By not protecting a minority, it really reflects that American membership is not valid. We need to remember that we believe in ideals and that we need to uphold them.”

Tamai explains that, during the war, the Japanese-American community suffered significant economic losses, in addition to the psychological trauma of relocation and incarceration.

Japanese Americans were sitting on prime real estate by the 1920s and 30s, Tamai said. Areas like Terminal Island, Culver City, and the Palos Verdes Peninsula in the Los Angeles area were almost all Japanese-American farmland.

The Japanese immigrants who settled in Washington State’s Bainbridge Island worked in local sawmills and farmed strawberries. They became the first community to be forcibly removed from their homes and incarcerated.

“They lost out, didn’t get to participate in the boom of the wartime economy,” Tamai said. “They were farming a huge amount of niche crops. They established farming in low-yield, high risk crops like artichokes, melons, strawberries and asparagus.”

As Japanese Americans were relocated during World War II, some responded by not speaking Japanese or finding ways to prove their "Americanness," Tamai said, noting the 442nd Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army, which was composed entirely of Japanese-American troops. It is the most highly decorated unit for its size and length of service in U.S. Military history. The soldiers, who fought primarily in Europe, took it upon themselves to fight harder and longer than their counterparts as one way of showing their allegiance to the United States.

During the '70s, Japanese Americans launched a campaign to call for redress from the U.S. government. Their calls led to the signing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which granted former incarcerees $20,000 in reparations—a total of $1.2 billion for surviving incarcerees. Four years later, an amendment was signed to add additional funds to ensure all survivors were receiving payments.

Moving Forward

"There are still some people who don't want to talk about it. My sister doesn't want to talk. She relies on me to tell our story.”

On Nov. 21, 1945, three years after its establishment as the first of the 10 camps, Manzanar became the sixth camp to close. A year prior, in 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court had delivered two decisions that would effectively end incarceration for Japanese Americans: while Korematsu v. United States found that the forced relocation of Japanese Americans from the West Coast was constitutional, Ex parte Endo found that U.S. citizens who were shown to be loyal could not be detained.

By the end of 1945, nine of the 10 camps had closed.

Seventy years later, the mostly barren site holds a few recreated barracks, a watchtower, a visitor center, and a cemetery on the valley floor. A few signs scattered along the highway read: “Manzanar Ahead.”

Umemoto, whose memoir “Manzanar to Mount Whitney: The Life and Times of a Lost Hiker” was published in 2013, returns to Manzanar from time to time to speak to groups and give tours through the place he once lived.

Michelle Nakamura, one of Umemoto’s daughters, says she remembers going to Manzanar as a child.

“He would take us on these adventures off the beaten track,” Nakamura told NBC News. “We knew it was really important to my dad, but he was this quiet guy.”

There wasn’t much left of the camp in those days, only some large concrete slabs that marked foundations for the barracks and other structures, she said.

Last week, on a bright and windy November morning, Umemoto led a group of 11 students and their professor from the University of Massachusetts Boston through the site. For the students, who were taking an honors class on Japanese-American incarceration, hearing from Umemoto and seeing Manzanar for themselves brought to light how essential education was on what happened during the war.

“I told my roommate and he didn’t believe me,” Madilyn Kane, a senior English and psychology major, told NBC News.

Incarcerees like Umemoto and Houston say that confronting the trauma they experienced is not only an opportunity to teach the world, but an opportunity to reflect on how far the country’s come.

“We had to be really American to be American,” Houston said. “Now it’s not like that. I think that we are accepting [our identity]. We are a very multi-racial, multi-cultural country.”

She adds that the more the stories of Japanese-American incarceration get shared, the better the picture that can be preserved for posterity. “If we forget, we’re likely to do it again,” Houston said. “It’s important that we keep up our progress.”

For Nakamura, the camps symbolize the pain, hardship, and loss endured by Japanese Americans, as well as the remarkable resilience displayed by the community—a community that includes her own family.

“My dad, he wants people to see the camp not as the tragedy it was, but as the beautiful thing that the community became,” she said. “When I see pictures of the camp, they had dances, baseball…they’re digging up koi ponds. It just seems like they built an amazing community. I feel proud to be Japanese American.”

FURTHER READING:

- Digital Project Aims to Preserve Stories of Incarcerated Japanese Americans

- The Untold Stories of Internment Resisters

- The Untold Story: Japanese-Americans' WWII Internment in Hawaii

- From Internment to Advocacy, One Family's Journey

- 'Only the Oaks Remain': One Woman's Fight to Preserve Her Heritage

- 'Allegiance' Brings Japanese-American Internment Story to Broadway

- Campaign Urges USPS to Create Stamp in Honor of Japanese-American WWII Soldiers