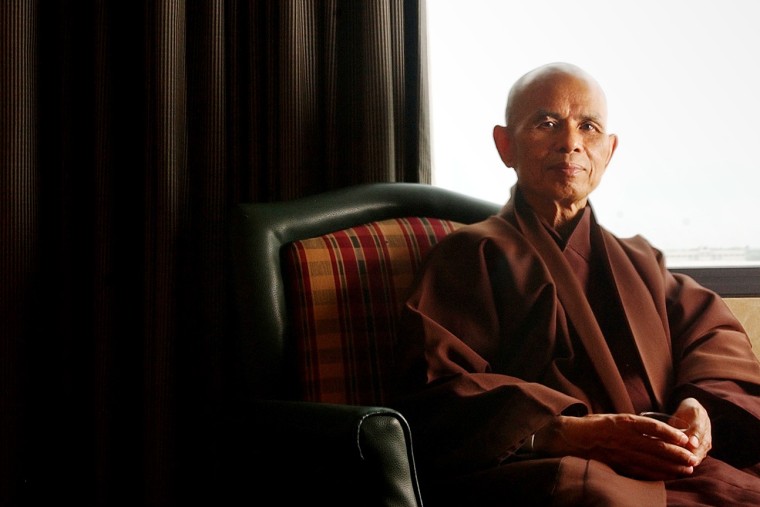

Whatever you’re doing, pause, take a breath and come back to your body, said Brother Chan Phap Dung, recalling a lesson he learned from his teacher, revered monk Thich Nhat Hanh, who died Saturday.

“Drinking a cup of tea, you can do it mindfully,” Phap Dung said. “When you’re really present with a cup of tea, you’re not wanting anything else, you see the miracle of drinking a cup of tea. I learned that from my teacher.”

Known as the father of modern mindfulness and one of the key figures in popularizing Buddhism in the West, Thich Nhat Hanh's death was confirmed by Plum Village, the monastic community he founded in France after being exiled from Vietnam.

Those who knew him are paying homage to a man whose kind and unassuming demeanor was coupled with a strong social justice mindset. But it was his focus on the little things that rocketed his teachings to fame in the U.S., experts said.

“He had this way of being accessible, particularly to Asian American Buddhists who might be second generation or third generation,” said Funie Hsu, a professor at San Jose State University who focuses on Buddhist and Asian American studies. “The language that he used was this articulation of complex Buddhist ideas in digestible, applicable ways that connected to points of reference in our day-to-day lives.”

When Phap Dung landed in Los Angeles, he wanted his war-torn home in Vietnam and the boat trip his family took across the sea to be behind him. A 9-year-old refugee starting a new life in 1979, the urge to push away his culture was hard to fight.

“I didn’t feel like I belonged to Vietnamese culture or to American culture,” he said.

After graduating college and working for a few years, he realized he needed something different. In search of an equilibrium, he turned to Deer Park Monastery, a mindfulness and monastic training center. In the hills of Southern California, he had his first interaction with the monastery's founder: Thich Nhat Hanh.

“He helped me heal,” Phap Dung said.Referring to Thich Nhat Hanh fondly as “teacher,” Phap Dung remembers those lessons in cups of tea and in the pauses he takes throughout the day.

“You drink your coffee, your tea, so you can get to the next thing,” he said. “And when you get to the next thing, you want the next thing. No wonder people get sick and get depressed.”

Thich Nhat Hanh’s teachings introduced this concept of mindfulness to the Western world, coinciding with the U.S. popularization of Buddhism and Eastern spirituality in the 1960s and '70s. As a professor at Columbia University, as well as a prominent peace activist during the Vietnam War, he talked about Buddhism as a way to be more centered day to day.

“He [didn’t] have much,” Phap Dung said. “He’s very simple and very humble, but also very strong and very determined to help the world. There’s this kind of relentless concentration to be a benefit to the world.”

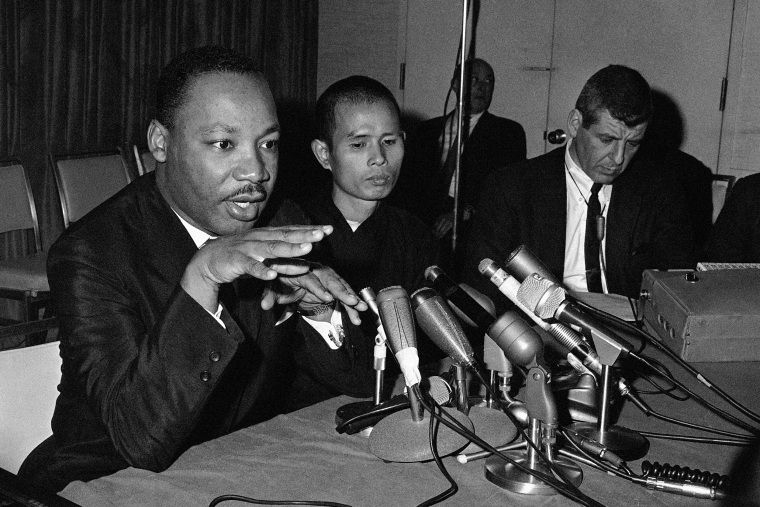

Thich Nhat Hanh’s activism during the Vietnam War represented the birth of what followers call "applied Buddhism," in which those who practice use their mindfulness to advocate for others in the real world. It was a concept that impressed civil rights activists including Martin Luther King Jr., who nominated Nhat Hanh for a Nobel Peace Prize after the two met in 1966. The monk's 1995 book, "Living Buddha, Living Christ," propelled him to recognition as a spiritual leader beyond Buddhism.

“Western Buddhists particularly had seen Buddhism as purely about individual liberation,” Melvin McLeod, editor-in-chief of Buddhist publication Lion’s Roar, said. “He added that the obligation of a Buddhist is to actually address the societal suffering that exists.”

Thich Nhat Hanh spoke in simple terms, breaking down the teachings of Buddhism and modernizing its rules for a younger generation.

“It made sense to people,” Hsu said. “And allowed them to feel that these religious teachings that are thousands of years old can have a place in their lives.”

As decades passed and technology became more ingrained into daily life, Phap Dung said the need for Thich Nhat Hanh’s lessons grew.

“We’re so tense in our day-to-day activities,” he said. “Our shoulders are stiff, and our hands are tight. When we sit, we’re not relaxed; we’re not in our body. Our mind is always thinking about what’s next.”

Beyond his wisdoms, Phap Dung remembers the small moments his teacher always focused on. When they sat for a meal, often a bowl of rice with bamboo shoots plucked from his garden, he said Thich Nhat Hanh was fully present. “He really lived his life,” Phap Dung said.

The community of thousands that he built all over the world sent him off with virtual memorials over the weekend.

“The death of a great teacher is always an important moment,” McLeod said. “His teachings will continue, and his community is vibrant.”