The University of Southern California announced last week that it will make amends for its discrimination against Japanese Americans during World War II, when the U.S. government deemed the community a national security threat.

USC President Carol Folt will award posthumous degrees and apologize to the students of Japanese descent whose schooling was interrupted when they and their families were forcibly displaced and put into concentration camps. At the time, the university refused to release transcripts for students who wanted to transfer, sabotaging their chances to complete their educations. USC is now trying to identify the families of about 120 students who were affected during the 1941-42 academic year.

“I think we’re starting to understand … there’s things that have happened in the past that are not things that we’re proud of,” Folt told NBC Asian America. “It only does good to acknowledge that — to find the source of problems, to apologize, but maybe even more importantly ... to make sure that these sorts of issues do not happen.”

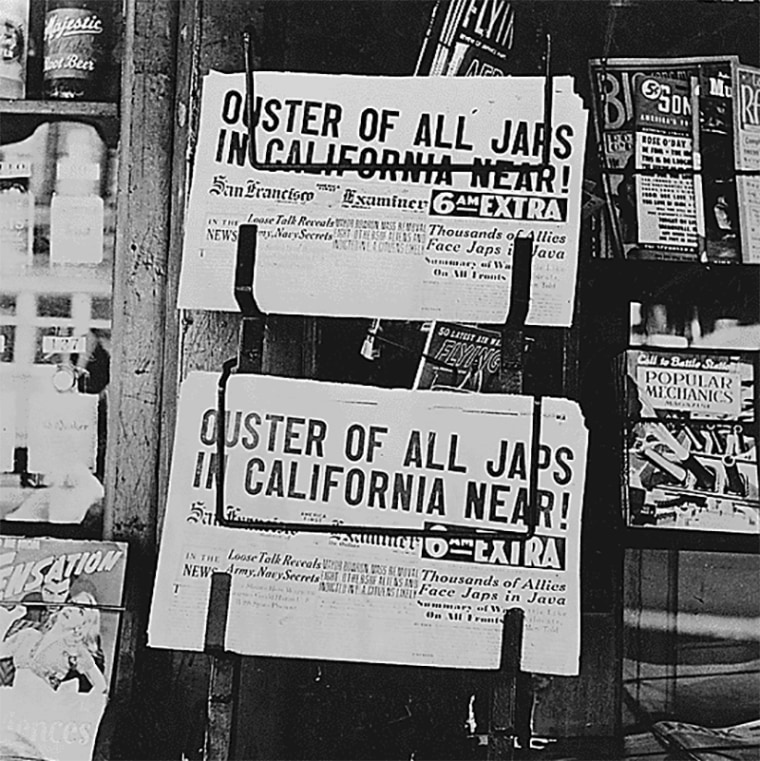

Many college students were left with uncertain futures after President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in 1942, mandating the removal and subsequent incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent who lived in the designated “military zones” along the West Coast. The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, formed by organizations, college administrators and several Quaker religious groups, encouraged schools in other parts of the country to accept students of Japanese descent, most of whom were children of Japanese immigrants, known as nisei.

The council was largely successful. Schools on the West Coast released the students’ transcripts, helping many students graduate from other colleges, said Brian Niiya, the content director of Densho, a nonprofit Japanese American history and education organization.

The council “allowed for some thousand of the nisei students to leave camp and to continue with their education on the outside. So that was a really important step,” Niiya said. “Others, though, were never able to continue with their education.”

Some students chose to remain with their families in concentration camps, and others joined the military to prove their loyalty to the U.S. But some who wanted to continue their studies found that schools like USC stood in their way, Niiya said. Under the leadership of Rufus B. von KleinSmid — the university’s president at the time, whose name has since been stripped from campus buildings because of his racist beliefs and his support for eugenics — USC campus officials withheld the documents.

Not only were many USC students forced to abandon their studies during the war, but when Japanese American students tried to re-enroll at USC or obtain their transcripts afterward, they were also allegedly told to start their college educations over again. Some have said officials claimed that their paperwork had been lost.

“California had been the center of the anti-Japanese movement for decades since the early 1900s. It’s safe to say that the vast majority of Californians, including those in power ... were supporters of the incarceration or the removal of Japanese Americans,” Niiya said. “It’s not surprising or remarkable that this university president would have those views. That was just the mainstream at that time.”

Niiya said USC’s newest efforts to make amends are the result of the Japanese American redress movement that began in the 1970s. Activists sought reparations and apologies for the government’s role in Japanese Americans’ loss of their civil liberties. Niiya said that for many, restitution came in the form of back pay that was restored or service time for employees who had been fired. As time went on, the movement pushed for honorary degrees for students.

USC had previously given honorary degrees to surviving students in 2012 after a 2009 law required California public universities to do so. But the school wouldn't give the same honor to those who had died, citing a policy against awarding posthumous degrees. Under Folt, it made an exception.

She said the plan was set in motion after she got a letter from Jonathan Kaji, the president of the school’s Asian Pacific Alumni Association, which has been pushing for such action since 2007. Holt said it was Kaji, who had protested the previous awards ceremony because it didn’t honor those who had died, who laid bare the injustices to her.

“I just immediately thought, ‘I don’t know how it happened, but this is something we can acknowledge and make right,’” Folt said. “My efforts were on fixing it, rather than trying to understand why it didn’t happen before.”

Folt said the university is working with several Japanese American community organizations to find the families of former USC students and is calling on the public to help. She said the degrees and the apology will be presented to descendants at an awards ceremony next spring.

Even though the ceremony comes 80 years after the students were forced to leave school, Niiya said, it is an important step in both healing and moving forward.

“For individual families, it’s really important in many cases that the grandparents or great grandparents are getting this posthumous recognition,” Niiya said. “But I think on a broader level, it’s just a way to keep this incarceration story at the forefront, just as a reminder ... to continue to be vigilant in what we do now.”