Four years after President Obama announced the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, more than 728,000 young undocumented immigrants have been approved for the program.

"I'm as productive and as much of a part of this community, part of this country, as anyone else who have come here with nothing and tried their best to make the best of themselves," Ivy Teng Lei, 25, told NBC News.

Lei said she's been compelled lately to speak out more about her status in light of the rhetoric on the campaign trail. "We really have to start putting faces to these stories," she said.

Read more reflections from DACA recipients on how the program has changed their lives:

Riya Nathrani (Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands)

DACA has provided me with countless opportunities to financially support myself, my education, and my family. Prior to being a DACA recipient, I was unable to work, open a bank account, or even apply for a Social Security number. However, upon receiving DACA, I began to pursue a college education, applied for a part-time job on my college campus, and was able to receive a few scholarships to support my education.

DACA changed my life for the better. If I had not applied for the program, I cannot imagine being able to complete my education or supporting myself financially. I finally had the same opportunities that my U.S citizen counterparts had been taking advantage of throughout their entire lives. Thanks to DACA, I can now achieve my personal and professional dreams. DACA may not be a pathway to citizenship, but it is surely the next best thing.

The choice of being brought to a new country at a young age was no more mine than being born, but the following years taught me how to prevail over hardships and maintain hope. I grew up pledging allegiance to the U.S. flag every day in my classroom while learning U.S. history and being immersed in the American education system.

My family's desire to pursue the American Dream has given me countless opportunities and helped me discover my passion in teaching. I decided to pursue a degree in education at the Northern Marianas College in hopes that I will be able to teach and mentor marginalized youth and promote positive racial identities in my community. I wish to help my students create a better life for themselves through access to quality education. With DACA, I have finally become a valuable asset to my community and its economy.

Last month, I graduated with my bachelor's degree in education from the Northern Marianas College and received the highest honor among my graduating class, Summa Cum Laude.

Raymond Partolan (Atlanta, Georgia)

#MyAsianAmericanStory is not unique. Just like hundreds of thousands of other parents, my parents brought me to the United States in search of opportunity. I was one. We left the Philippines hoping that our new land would mean my mother would no longer have to sleep on wooden boards, as she did every night for 28 years, and my father would be able to practice his expertise in physical therapy.

1994. For months, my mother, father, and I bounced around from couch to couch in search of a place to make our permanent home. Finally, we settled in Macon, Georgia, and, for almost 10 years, we thrived as we began to make the United States our new home. Then, everything changed.

2003. We applied for our green cards. In order for us to qualify, my father had to pass a battery of English competency tests to prove to the Immigration and Naturalization Services (INS) that he could communicate effectively as a physical therapist. He passed every single section of the test except for one — the speaking section. After taking the tests over and over, he kept failing that one section by very small margins. Eventually, the INS denied our applications.

"On the anniversary of DACA, we celebrate how far we’ve come, but recognize that we still have a ways to go."

We became undocumented, “illegal immigrants,” “TNT" (tago ng tago, which means hiding and hiding in my native language of Tagalog), or “illegal aliens.” Whatever one calls it, we lost our right to legally stay in this country. My family had to make a decision. Do we stay in the United States and risk arrest and deportation at any given moment or do we go back to the Philippines, a country I left when I was a mere one year old? We decided to stay.

My parents told me never to tell anyone about my immigration status. If I told the wrong person, we could be reported and life, as we knew it, would be over. For the most part, I held it in. The hardest part about being undocumented was feeling like there was no one who would truly understand what you were going through. That no one would ever see the real reason you live in fear and anxiety every single day and why you cannot do the things that your friends can do.

When DACA was announced in 2012, I jumped for joy. Finally, I could come out of the shadows and live a more dignified life. Without DACA, I wouldn’t have been able to take my dream job with Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Atlanta, the first nonprofit law and advocacy center dedicated to the civil, social, and economic rights of Asian immigrants and refugees in the Southeast. A large part of my job is dedicated to encouraging Asian Americans to be civically engaged in their communities — primarily through voting. Even though I cannot vote myself because of my immigration status, encouraging others to exercise this very important right is my way of serving the community.

#MyAsianAmericanStory is not unique and it is not not unique. It is my own, yet it is shared by so many millions of others. It’s time for America to stand up and to recognize the contributions of Asian-American immigrants to this country, especially those who are still in the shadows. On the anniversary of DACA, we celebrate how far we’ve come, but recognize that we still have a ways to go.

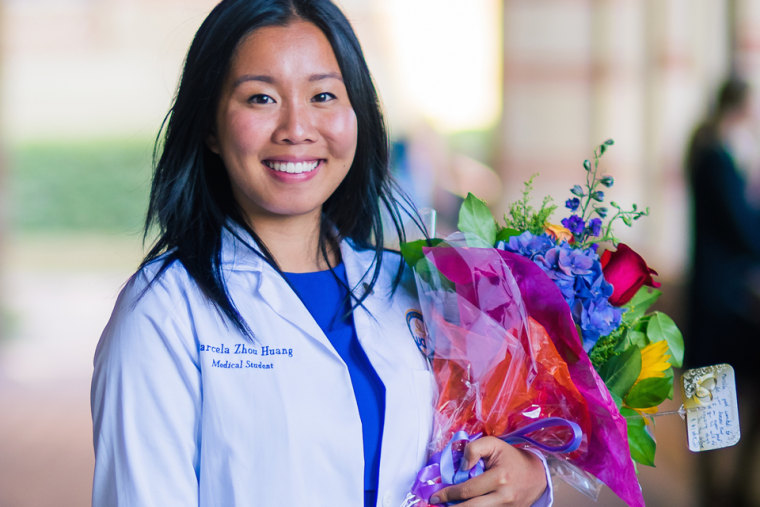

Marcela Zhou Huang (Los Angeles, California)

My parents followed a wave of immigrants from the rural villages of southern China to Mexico in the 1980s. After they settled in Mexicali, a Mexican city bordering California, my sister and I were born. Growing up, my parents ensured that my sister and I maintained our Chinese ancestry while also embracing the Mexican culture. Above all, our parents taught my sister and I to see education as the most invaluable asset a human being could have. However, none of my parents' teachings prepared me for the identity crisis I encountered when I first moved to the United States as a 12-year-old Mexican-born Chinese looking to expand my education.

Having been born and raised in Mexico to Chinese immigrant parents, I felt like an oddity in this new country, garnering undesired attention, while I struggled to find an identity of my own. My identity struggle was further intensified with the addition of a new label: undocumented immigrant. Living in a border town, I was conditioned to be ashamed and secretive about my immigration status. While my family continued to live in Mexico, I lived in disguise as an Americanized Chinese in Calexico. Border patrol agents scoured every inch of the city and were also my next door neighbors. However, my fear of deportation silenced me as I guiltily witnessed others become suspects of illegal immigration simply by the color of their skin.

Despite the challenges and stereotypes that came with the label of being an undocumented immigrant, I persevered and graduated as the valedictorian of my high school class. However, my American dream was further impeded by my invisibility in this country from the lack of a Social Security number. Yet, with self-perseverance and drive, I refused to accept such fate — I transferred out of community college in one year and completed my bachelor’s degree at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) within three years of graduating high school.

Shortly after becoming the first person in my family to obtain a college degree, I was granted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), giving me legal presence and the ability to work in this country. DACA also gave me access to many luxuries: a driver's license, a credit card, and most importantly, a relief from the constant fear and depression I lived for a very long time.

RELATED: True Story Inspires Web Series Tackling Undocumented Teen Life

DACA opened a world of opportunities to my research endeavors as a clinical research coordinator and I also began volunteering as a Spanish interpreter at the UCSD Free Clinic to provide comprehensive medical services to the underserved. Many experiences along the way have opened my eyes to the severity of health disparities in our nation. With increased exposure to stories that resonate with my own, I learned to embrace my legal status and the multicultural union in me. This has empowered me as a Mexican-Chinese-American to have a personal commitment to improve health conditions for the underserved. I aspire to become a physician that is not only concerned with the physiologic needs of the patient, but also one that strives to understand the social challenges intricately weaved into their lives. Because of DACA, I am attending one of the finest medical schools in the country and I will have the privilege of becoming a physician that will continue to fight for the socially disempowered.

Saba Nafees (Fort Worth, Texas)

It was the long and dreary night of May 11, 2015. Utterly exhausted and yet trying to plan what I’d talk about in the panel the next day, I found myself on the verge of a profound realization. The panel the following day was part of the first-ever White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (WHIAAPI) Summit and I was to talk about #MyAsianAmericanStory and how DACA had changed my life.

I realized that immigration had shaped every aspect of my life and that of my family’s. I shuddered with the realization that there was not a single part of my world, academics, family, love or the future, that immigration had not molded.

Growing up in the vibrant city of Lahore, Pakistan, I dreamed of America. My grandparents lived there so I knew that I would get to move there with them someday and pursue the American Dream. My father worked hard and I was fortunate enough to have a first rate education at one of the best schools in the city. Many of the young children of Pakistan were not as lucky as me and my sisters.

Finally in 2004, we moved to America, the land of opportunity. We started our schooling and worked hard throughout. Eventually, we realized that our grandparents passing away would result in us living here without a sponsor. We were left with no choice but to stay. Going back to a torn country with bomb blasts in Lahore that shattered parts of the very building we lived in did not seem prudent.

That is when I realized that I was amidst two homelands and started to share my story along with other brave young Americans throughout the country. DACA was passed as an executive order in 2012 and it became the beacon of hope that someday a comprehensive reform would take place in the nation and allow for millions of Americans to finally feel at home.

RELATED: 'Eye of the Storm': Undocumented Dreamers Head to Battleground States

The morning of 12th of May, I was asked on national television why my fellow Asian Americans do not take advantage of DACA. It breaks my heart that so many young Americans are afraid to benefit from this resource that has changed hundreds of thousands of lives dramatically in the few years of its existence.

Later that afternoon, in a panel during the WHIAAPI Summit, USCIS Director Rodriguez spoke about a young student studying mathematics at her university and through DACA was able to find relief. It seemed exactly like my story but it wasn’t. The convergence of all of our stories is a remarkable testament to the fact that we all are Americans at heart, just trying to give back to the only home we have known for most of our lives.

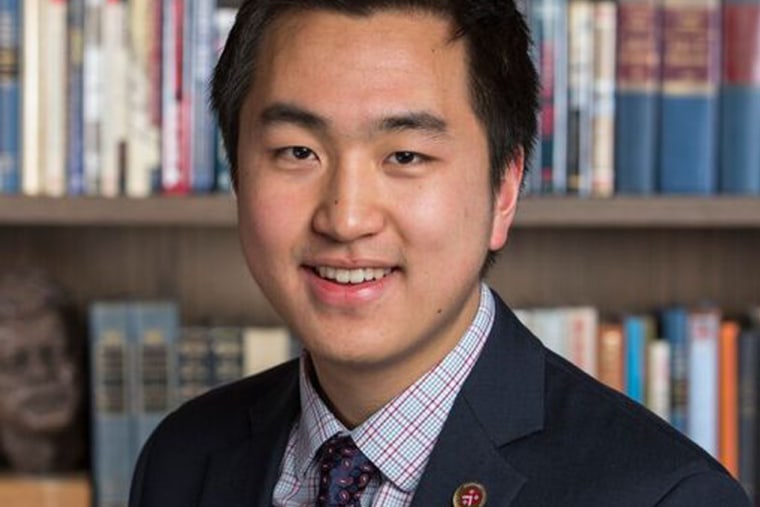

Jin Park (Boston, Massachusetts)

DACA was a game changer for me in many ways. Initially, the fact that I would have a Social Security number, work authorization, and the ability to apply for a driver’s license were immensely important in allowing me to work to help support my family.

"DACA was the reason that my First Amendment rights were secured in reality, and not just in speeches and in textbooks."

Our status had kept our family in perpetual uncertainty, and although there is still a lot of work to be done, having DACA allowed me to be proactive in supporting my family. Secondly, DACA allowed me to apply to universities and scholarships as a high-school senior with less uncertainty. I knew that applying to college as an undocumented student was incredibly difficult, and although this is still a reality for undocumented students, DACA did a lot to encourage institutions to consider undocumented students on equal footing with other students.

With the documentation that I was able to receive through deferred action, I was accepted to Harvard College, where I am currently a rising junior studying biology and government.

Thirdly and perhaps most importantly, DACA allowed me to speak freely and openly. Before DACA, I never told my friends or anyone I knew that I was undocumented. It was something that my parents and I kept to ourselves during late night conversations about the uncertainty of our future. DACA gave me a certain peace-of-mind about my presence here that was unprecedented. I felt that I could talk about my experience without the fear of being deported. In some ways, I felt that DACA was the reason that my First Amendment rights were secured in reality, and not just in speeches and in textbooks.

Although this is not a reality for my parents, I felt that with DACA, I could finally fight for their rights and the rights of other undocumented immigrants. Thus, I’ve been doing a lot of advocacy and academic work around immigration reform, and I’ve recently formed a 501(c)3 nonprofit called HigherDreams, which aims to provide resources for undocumented students applying to college. Now, I am interning in the NYC Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs working to provide coordinated and compassionate health care for immigrants in NYC, regardless of immigration status.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Tumblr.