LOS ANGELES — At the start of a pilgrimage last month to one of the 10 incarceration camps in California that held Japanese-Americans during World War II, an official associated with the camp was giving a speech about the need to resist President Donald Trump's policies and rhetoric.

Someone uttered an expletive in protest, then said, “This isn’t political," Kathy Masaoka recalled.

Masaoka said she yelled back, “This is political,” as shouting filled the room. Some in attendance angrily asserted that the space they were in, where so many of their ancestors had been forcibly relocated to after being removed from their homes, was indeed political, Masaoka recalled.

“One of the main things you take away from pilgrimages is the understanding that what happened with our families could still happen today,” she said. “And you have a responsibility to speak out about that.”

The weekend-long pilgrimage to the Tule Lake Segregation Center is one of several organized trips to former incarceration camp sites that often include cultural performances, interfaith ceremonies and walking tours.

The events allow third- and fourth-generation Japanese-Americans to reflect on their parents’ and grandparents’ experiences and others to learn about a period of U.S. history in which approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent, many of them U.S. citizens, had their constitutional rights stripped based on their race based on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

This year, the Tule Lake Committee wove the current political climate into its programming, holding a rally in solidarity with families being separated and detained at the Mexican border.

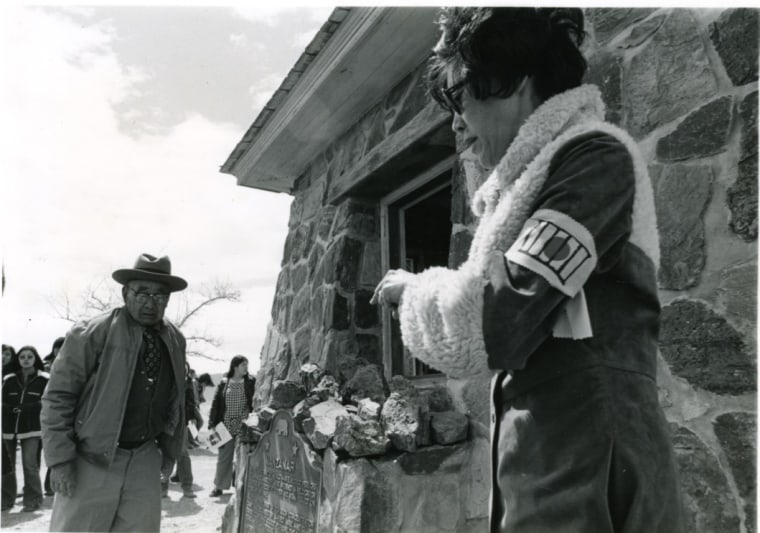

The rally look place in front of the Tule Lake jail, and attendees were encouraged to paint signs and join camp survivors and their descendants as they chanted “Kodomo no tame ni, they’re our children, set them free.” "Kodomo no tame ni" translates to “for the sake of the children” and is said to encourages others to think about and care for the next generation.

For the first time, the Tule Lake Committee created a Twitter account to document the pilgrimage, using hashtags including #FamiliesBelongTogether and #StopRepeatingHistory to argue that what’s happening now is not all that different from what happened in World War II and mustn’t be allowed to continue.

A Political History

Tule Lake's planned disruptions weren't the first time incarceration camp pilgrimages made political statements. According to Bruce Embrey, Manzanar Committee co-chair, the establishment of pilgrimages itself was a political act.

“In 1969 a group of young people, mostly ‘sansei,’ made the first trip back to Manzanar to figure out what had happened to their families,” Embrey said, referring to third-generation Japanese-Americans, the children and grandchildren of those incarcerated in the camps.

We were proud to be Japanese American, and we wanted to go back to camp to celebrate this acceptance and learn more about ourselves.

Fresh from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the group was inspired by the black community’s fight for civil rights and claim to their national identity, and they went off to find their own, Embrey said.

“The media caught wind of it and arrived at Manzanar asking what happened, and nobody had a clear answer because they didn’t really know,” he said.

In the years after World War II, it was common for family members to remain silent about incarceration, avoiding discussing the matter as a way to cope with the collective trauma they endured. Hungry to learn about what their families went through, members of the inaugural Manzanar pilgrimage deemed the site in California an important space to gather each year and unearth the history together.

Embrey’s mother, teacher and community activist Sue Embrey, became a co-chair of the Manzanar Committee, where she would develop the program over the next 36 years. Others in the community didn’t feel as strongly about the decision to bring attention back to the camps, Bruce Embrey recalled.

“Many people in the community, mostly the older generations, weren’t happy because it brought up the past and called attention to us as a whole,” he said. “Not to mention the fact that it highlighted our criticism of our own government.”

A major victory for the pilgrimages came in 1973 after aggressive lobbying from the Manzanar Committee helped earn the incarceration camp site recognition as a California State Historic Landmark. What meant the most to the community then, Embrey noted, were the words engraved on the plaque placed by the California Department of Parks and Recreation.

“The plaque reflected the true views of those who had been incarcerated,” Embrey said. “It used the correct words and terminology of the community, calling them what they were: concentration camps and not internment camps.”

The plaque also acknowledged incarceration to be a result of racism, as well as economic exploitation. Japanese-American families had known their imprisonment to be an injustice, but to have the state declare it as such was monumental and would play a role, Embrey contends, in empowering the Japanese-American community to seek redress and reparations from the government throughout the 1980s.

Kathy Masaoka, whose father’s family was incarcerated at Manzanar and mother’s at Gila River in Arizona, was in the thick of the redress movement as a member of the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations, a group of Japanese-American citizens who demanded an apology from the government. Masaoka had attended the Manzanar pilgrimage since 1971, and the coalition would use the annual event as a way to report updates on their progress as well as support for their cause.

“There were people in Congress and other groups like the JACL who were fighting for redress, too, but our community needed to stand up,” Masaoka said about the coalition. “Unless we stood up, we couldn’t really expect other people to stand up for us. When we went to Washington, D.C., as a delegation, we were all very ordinary people sharing our stories.”

The passage of the 1988 Civil Liberties Act, which granted $20,000 to camp survivors and a formal apology from the federal government, added another layer of meaning to the pilgrimages, and attendance at Manzanar and Tule Lake increased over the 1990s, according to organizers.

“I think we became more confident in our identities,” Masaoka said about the popularity of pilgrimages following redress. “What we had done was show that individual people can make a difference. Now we weren’t as ashamed of what happened. We were proud to be Japanese American, and we wanted to go back to camp to celebrate this acceptance and learn more about ourselves.”

Modern Day Parallels

Pilgrimage attendance spiked again following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, Embrey said, though the Manzanar Committee did not keep attendance statistics until the mid 2000s. The attacks resulted in discrimination against Muslim Americans that mirrored the way the Japanese-American community was treated after Pearl Harbor, pilgrimage attendees said.

Sean Miura, a fourth-generation Japanese-American community organizer and writer based in Los Angeles' Little Tokyo, was one of those mobilized into attending his first pilgrimage as a result of the attacks.

He was 12 at the time and remembers his best friend’s family, who was Muslim American, hanging a giant American flag outside their home.

“9/11 impacted my own understanding of my family’s history,” Miura, whose family was incarcerated in Manzanar, Gila River, Jerome, and Tule Lake, said. “Suddenly I was making all these connections back to what my family had gone through before. Before, it was an abstract concept, but seeing this kind of racism happen in real time was alarming.”

Miura attended the Manzanar pilgrimage with his mom and witnessed community organizers speaking against the hate crimes and racial profiling facing people of Middle Eastern descent. Since 9/11, the Manzanar pilgrimage has invited Muslim-American groups to participate each year.

The 2016 election and resulting policies affecting immigrant communities, including the travel ban and “zero-tolerance” border policy, has politically charged pilgrimages once again.

“The night of the 2016 election, I remember having this moment of, ‘Oh, has all the work we’ve done been for nothing?’” Miura said. “It feels like everything has been erased. But going to the Tule Lake pilgrimage has me thinking again about how we can still use our story in an efficient way.”

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.