Before his kindergarten classes begin for the day, Raynardo Antonio Ocasio watches from his mother’s third-floor bedroom window as his classmates line up on the sidewalk below.

“It actually makes him sad,” said his mother, Mayra Irizarry. “He doesn’t understand why he’s not going to the school. He wants that interaction. He wants to be around kids.”

But Raynardo, 6, has been banned from his classroom since September.

After attending in-person classes for four weeks last fall at the Zeta Charter School, across the street from his apartment in northern Manhattan, Raynardo was banished to the school’s virtual classes for failing to wear a mask and follow other Covid-19 safety rules.

The school said pushing Raynardo out was necessary to keep teachers and students safe at a scary moment in the pandemic.

Administrators across the country made similar decisions as they tried to reopen safely amid fraught politicized debates and angry disputes over masks and public health. Student advocates in six states told NBC News that they’re working with numerous students who’ve either been excluded from in-person classes or have been threatened with exclusion if their behavior doesn’t improve.

School leaders may be acting in the interest of safety, but advocates say that removing students from in-person classes because of their behavior may violate those students’ rights, especially if they have disabilities. Federal law requires public schools like Zeta to provide all students with the support they need to succeed in the most appropriate classroom for them, which could mean bringing in a counselor or working with parents to improve a child’s behavior.

Advocates say the students they’ve seen removed from in-person classes this year are the same ones who’ve been traditionally more likely to be removed from class: children with disabilities, who have a harder time following some rules, and Black or Latino children who are more likely to be punished for their behavior than their white classmates.

These students were already more likely to struggle in school than their peers, and they’ve taken the biggest hit during the pandemic, said Lorraine Wright, a civil rights and educational justice advocate in Virginia.

They’re also the students who can least afford to miss out on in-person instruction, Wright said.

“This is the new face of denial of access to public education,” she said. “It’s just a new way to send kids to an alternative setting. Now it’s just easier and covered under the guise of Covid protection.”

‘Fear was palpable in the air’

The Zeta Charter School opened for in-person instruction last August at a time when most major public school districts were planning to start the year with mostly virtual instruction.

“Our families needed us,” said Emily A. Kim, the founder and CEO of the four-school 900-student Zeta network.

Months before vaccines would be available, Kim asked teachers to volunteer to come into the school so that a small group of students — mostly students with special needs and those whose parents were essential workers — could return to face-to-face instruction.

Raynardo was offered one of those student spots, but things didn't go well.

Raynardo has a speech and language impairment that makes it hard for him to comply with instructions. He had difficulty expressing himself, especially while wearing a mask.

Kim said the school brought in a psychologist to support Raynardo and made numerous other efforts to help him before deciding to send him home for virtual classes.

At the time, she said, New York was still reeling from the pandemic’s onslaught of panic and death.

“Covid fear was palpable in the air, everywhere,” Kim said. “We couldn't get school-based Covid testing for our teachers, and there was no vaccine on the horizon so everything was just a big unknown.”

The decision to send Raynardo home wasn’t meant to be permanent, Kim said, but because of the need for social distancing, the school does not yet have room to offer him his spot back.

Raynardo has now been attending school virtually for more than seven months, missing out on developing social skills and struggling to learn, his mother said.

“It’s a nightmare, a total nightmare,” said Irizarry, who works an overnight shift as a nurse in a New York City jail and now must stay awake through the school day to keep her easily distracted son engaged in the online classes he hates.

“I think my son is entitled to the education that they give there,” Irizarry said. “He shouldn't be pushed out because they probably don’t want to deal with him.”

‘Plausible deniability’

Advocates say what happened to Raynardo amounts to an informal removal: A school takes a child out of a classroom for what administrators see as bad behavior but doesn’t give the family a chance to contest the punishment — and doesn’t trigger a report to the state, the way a suspension or expulsion would.

Even before the pandemic, informal removals were one of the most common complaints to the Protection and Advocacy Systems, a national network of disability rights agencies that receive thousands of calls per year, said Diane Smith Howard, the managing attorney for criminal and juvenile justice at the National Disability Rights Network, which supports the advocacy hotlines.

Now, with the pandemic creating both more rules for students to follow and new remote learning options, advocates say they believe the practice is becoming even more common.

“I suspect this is happening a lot more than we know,” said Margie Wakelin, a staff attorney at Pennsylvania’s Education Law Center. “This is definitely not just a practice of one school or school district.”

For more of NBC News' in-depth reporting, download the NBC News app

But many parents don’t realize they could make a legal argument to keep their child in the classroom, said Perry Zirkel, a professor emeritus of education and law at Lehigh University, who tracks special education court cases and complaints.

Virtual instruction “is a very restrictive placement,” Zirkel said. “The kid is now at home and likely not getting the same level of services, and now he’s being excluded from school and from interaction with other kids.”

Kim, from the Zeta network, said she doesn’t agree that moving a student from in-person to remote schooling in the midst of a public health emergency constitutes a change in a student’s placement. She said the school made a “difficult decision” to send Raynardo to virtual as part of a commitment to teacher and student safety.

Many schools see it the same way, believing the pandemic has given them some wiggle room as they figure out how to reopen safely, said Smith Howard, of the National Disability Rights Network.

“What I have seen is a belief among school administrators that somehow, because of Covid, the original federal requirements don’t apply,” she said.

As Smith Howard sees it, federal law is clear that students with special needs should be given support to succeed in the classroom — and a meeting of teachers and parents should be convened before they’re formally moved out.

Covid-19 doesn’t change that, she said, but figuring out what support efforts might prevent a child from acting out can be difficult.

The online classes that schools created to respond to the pandemic have given schools “plausible deniability,” Smith Howard said. “As long as virtual is an option, it’s easier to keep the child out on virtual than it is to provide the services.”

'Bad for the school and bad for Winston'

It’s also easier to put a student on virtual instruction than it is to go through the process of expelling them, said Wakelin, from the Education Law Center in Pennsylvania.

She’s working with two students whose schools threatened expulsion before moving them to virtual instruction.

Winston Brown, 15, who has an intellectual disability and a speech and language impairment, got in trouble at the Multicultural Academy Charter School in Philadelphia last month for writing a threatening note and holding a door shut, briefly preventing a teacher from leaving a classroom.

Raheem Nixon, 19, who has learning disabilities, got out of jail last summer after serving time on misdemeanor theft and assault charges and could face expulsion from Wilson High School near Reading, Pennsylvania, for getting caught last year with a real-looking BB gun at school.

But neither school has begun expulsion procedures, Wakelin said. Instead, these students were sent to virtual instruction without a hearing where they could formally dispute the accusations, or provide context by telling their version of events.

Wakelin believes both students’ schools are using the pandemic, and the fact that “virtual instruction has been so normalized” this year, as a way to sidestep the legal process and avoid the extra scrutiny and oversight that can come to schools that expel too many students.

Scott Walsh, the principal of Winston’s school, said student confidentiality laws prevented him from commenting on Winston’s situation, but he strongly denied that his school has violated any student’s rights.

When Winston got in trouble in March, he was not in a typical face-to-face classroom. He was participating in a program that allowed a small group of students to come into the school building to get extra support from instructors for their virtual classes, provided they followed basic safety rules, his mother, Gilian Mcleish, said.

After the March incident, Winston was sent home to do virtual instruction without in-school support and his mother, before speaking with an attorney and learning she had other options, said she signed a “probationary contract” with the school in which she agreed to keep him home on virtual until the end of the school year to avoid expulsion.

“They said expelling is going to be bad for the school and bad for Winston,” Mcleish said, adding that the school told her that if Winston had an expulsion on his record, he would have difficulty finding another school.

When the school announced in late March that it would bring students back in person in May, Mcleish lamented that her son wouldn’t be able to participate.

After NBC News contacted the school, however, Mcleish got a call last week telling her her son could, in fact, join his classmates in person this week. The first day of in-person classes was Monday but, at this point, Mcleish said, she’s not interested. She no longer trusts the school and doesn’t believe her son will get the help he needs there.

“They told me he was out of the school,” she said. “How would you feel?”

Nixon, meanwhile, is a new father with ambitions to go to college. But he doesn’t think he’s getting the support he needs for learning and other disabilities in virtual classes. He’s asked to attend school in person.

“If I’m in front of a teacher, I can learn way better, he said.

A spokeswoman for the Wilson school district said the district, due to privacy concerns, doesn’t comment on matters involving students.

Students like Nixon, who have disabilities, criminal histories or become young parents, need more resources and support in school, not less, Wakelin said. But she believes his school doesn’t want to deal with him.

“He’s being told that he has to do this program that no one says is appropriate for him,” she said.

‘Fair is fair’

In New York, Irizarry has grown increasingly distressed watching Raynardo struggle with online learning.

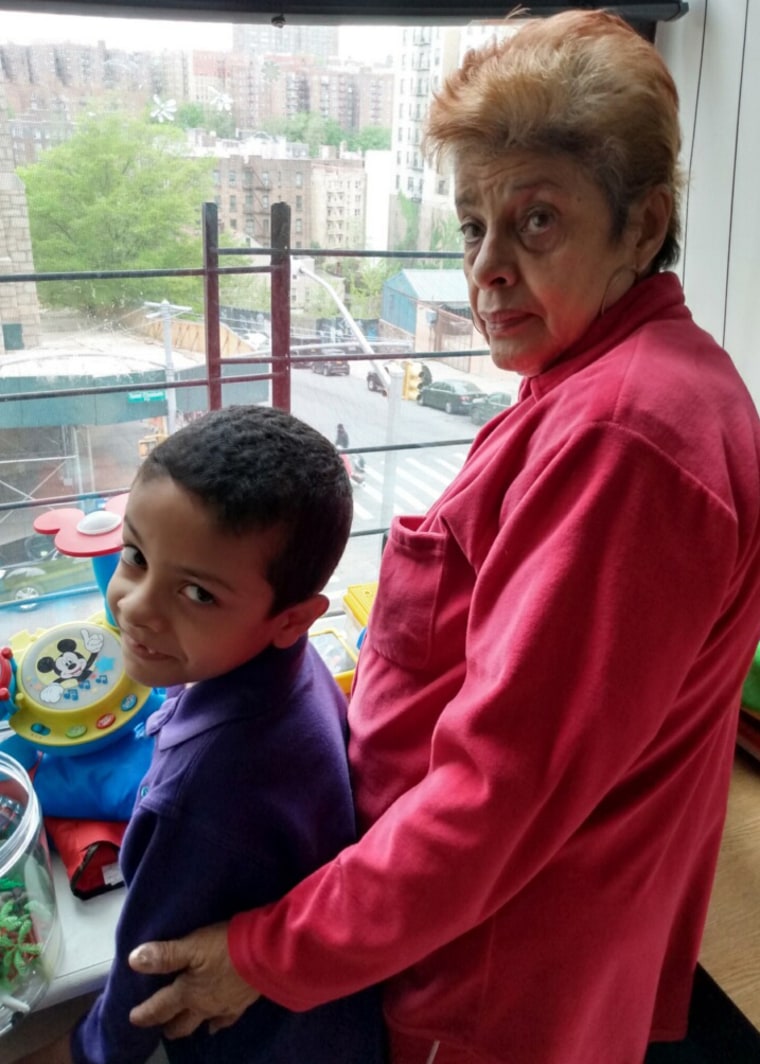

Raynardo’s grandmother takes care of him in the morning until his mother gets home from work, but the older woman, who is from Puerto Rico and more comfortable speaking Spanish than English, doesn’t have the tech savvy to help her grandson log into his classes.

The school says Raynardo is doing fine academically and won’t have a problem advancing to the first grade. But a special education evaluator with the New York City Department of Education who observed Raynardo in his online classes last year found that he was only engaged 8 percent of the time.

“He doesn’t stay on the computer. He just gets up,” Irizarry said. “When he comes to math, he doesn't understand. He’s unfocused.”

The family’s lawyer, Michael Athy, a staff attorney with New York’s Advocates for Children, said the family applied for a meeting with city education officials to argue that Raynardo’s removal amounted to a punishment for actions related to his disability, but a scheduled meeting was canceled.

Irizarry could transfer Raynardo to a different school, but she fell in love with Zeta the first time she toured it and that’s where she wants her son to go. “Fair is fair,” she said. “I’m going to fight for him all the way to the end.”