This story about teacher diversity was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

PHOENIX — When Sandra Jenkins started teaching at Betty H. Fairfax High School in Phoenix 14 years ago, she had three Master’s degrees and four teaching certificates. But what most strongly informed her passion for teaching was the support she received growing up as an Black child taught by Black educators in her Mississippi hometown, and at her alma mater, a historically Black college.

“I know the impact. I’m a beneficiary of what that’s like,” Jenkins said. “I just want to share that and make sure our kids know that we know it’s important to them.”

Jenkins said one of the reasons she has been teaching in the Phoenix Union High School District for so long is that she feels connected to her colleagues and believes her superintendent wants the same thing she wants: equitable student achievement.

“Ultimately, we all have the same goal,” she said. “If being more diverse and having more African American teachers and administrators would help our kids and our community, that’s what I think our district [superintendent] would do. He’s listening to us.”

There is no longer much debate that recruiting and retaining teachers of color is essential. All students, including white students, benefit from having teachers of color, according to a summary of the research by the Learning Policy Institute. In one study, students rank teachers of color higher than white teachers on multiple measures, including feeling cared for and academically challenged. Such rankings have been correlated to student academic gains. And students of color do better academically and are more likely to graduate and go to college if some of their teachers look like them, research shows.

And yet, few districts have achieved the goal of building a teaching workforce that looks like its students. While the percentage of white students has steadily decreased nationwide in recent decades — from 54 percent in 2009, to 47 percent in 2018 — nearly 80 percent of public school teachers are white, according to the most recent federal survey.

“The frustration is this has been a problem for 20 years,” said Margarita Bianco, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Colorado in Denver. “And while we know what needs to happen, it happens at a snail’s pace. It seems like it’s taking forever.”

But Phoenix Union is bucking that trend. The district, which is one of 30 public school districts in Phoenix, has managed to recruit and retain a diverse teaching force, with 40 percent of its educators identifying as Hispanic, African American, Asian or Native American, according to data. That doesn’t exactly represent the diversity of the student body here, which is 80 percent Hispanic and 8 percent African American, but it’s closer than in many other places.

“You have to first set that goal,” said Chad Gestson, Phoenix Union’s superintendent, who is white. “We are publicly and unapologetically clear that we want to have a teacher workforce that’s reflective of our community.”

By recruiting and then mentoring new teachers of color, listening to these teachers’ requests, supporting the development of culturally responsive curricula and promoting educators of color into administrative and district leadership positions, Phoenix Union is getting steadily closer to aligning its teacher and student populations.

In Phoenix Union, the focus on diversity begins with recruitment. Hiring panels reflect the district’s diversity and help avoid bias in hiring decisions. And candidates with nontraditional teaching backgrounds are considered.

Over the past two years, the district has hired six teachers from among its non-teaching staff, including an African American bus driver who recently earned his teaching credentials and now teaches history. Leaders here plan to use federal Covid relief funds to establish a system to find and support district employees who have an interest in teaching.

“Some districts miss that opportunity,” Gestson said. “These are educators. They might not be teachers, but they’re educators who already love schools and understand children. And they are committed to the district.”

Promoting district staff members into teaching positions is also working in the Highline Public School District outside of Seattle. A bilingual fellowship program for para-educators generates 15 new teachers every other year, said Steve Grubb, chief talent officer for the district. Since 2014, Grubb said, the largely Latino district has boosted teacher diversity by more than 30 percent, to a large extent by hiring Latino teachers to staff dual-language programs.

“This work is possible. It’s happening,” said Cassandra Herring, CEO of Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity in Austin, Texas. “We don’t have to be theoretical about what we’re doing. There are ways to move the needle.”

Teaching staff who reflect the student population

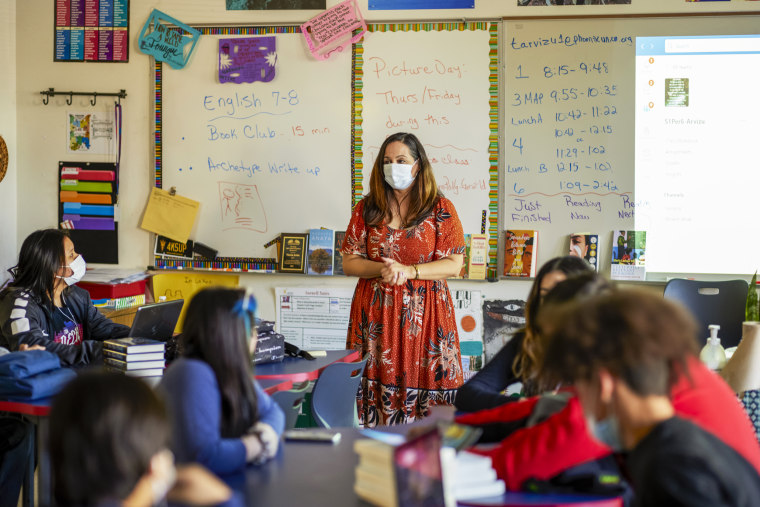

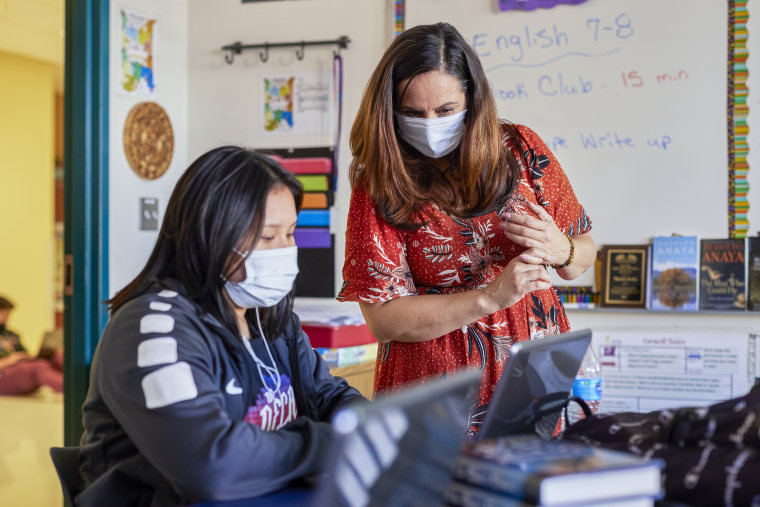

When Therese Arvizu interviewed for a job at North High School in Phoenix Union 12 years ago, she had a college degree and 11 years’ experience working in nonprofit groups, but no teaching credential. She was offered the job anyway, as well as a stipend to help her get a Master’s degree and credentials while she worked teaching English.

“At that time I was the only Chicana in the department,” Arvizu said. “Not anymore.”

This year, she said, district leaders listened when she and other teachers of color repeatedly asked for the opportunity to build a curriculum that more directly addressed their students’ racial, ethnic and cultural identities.

“That was the first time, in a professional setting, where we were able to talk about the literature that we grew up with, that had a lot to do with our identity and our love of literature,” she said. “It was a way for us to come to certain goals, to help students of color who were struggling.”

Arvizu’s classroom is decorated with posters of authors, including a large picture of Gloria Anzaldúa, whose book “Borderlands” is foundational to the course Arvizu helped develop, “English and the Chicanx Perspective.” Every student who enrolled in the course this fall is Latino, and most are Chicano, a term used by some Mexican Americans to describe their unique cultural heritage. District teachers also developed culturally relevant English courses for Black and Native American seniors.

“I think it does make a difference that the curriculum reflects them,” she said. “We have lengthier discussions in this course, and this has revitalized my excitement for teaching.”

Burnout, already high, has risen during the pandemic, especially among African American teachers, according to recent research by the RAND Corporation, a nonpartisan research firm. Nationwide, the number of Black teachers is declining, and ample research shows that Black teachers are more likely to leave the profession than their white counterparts, due in part, some teachers say, to feelings of isolation and racist behavior in the workplace.

And most states’ efforts at recruiting and retaining teachers of color, including Arizona’s, are abysmal. Almost 91 percent of teachers working in the state’s schools this year are white.

In contrast, Phoenix Union prioritizes hiring educators that reflect its student population, up to and including top district leaders. Of an executive team of 16, a dozen are people of color. Districtwide, more than half the administrators are people of color, according to district data.

Juvenal Lopez, the district’s executive director of talent, said that makes a difference when it comes to recruitment.

“When diverse candidates see that we have leaders that look like them and have similar goals in terms of serving students, we can attract people that wouldn’t otherwise consider Phoenix Union,” Lopez said.

Lopez said that recruitment was only a first step and that the district may soon add a new position, a retention specialist, specifically to help keep teachers in the district.

‘It’s all about building connections’

More than a thousand miles away, south of Portland, Oregon, the North Clackamas School District pairs new teachers with mentors and runs multiple affinity groups to support educators and administrators of color. Since 2014, North Clackamas has increased new teacher diversity by 35 percent, according to district data. The district has had a retention specialist, with classroom experience, on staff for the past five years.

“Coming from the classroom, I saw that revolving door of new teaching partners,” said Michelle Doyle, who was the district’s retention specialist for three years and is now an assistant principal. Doyle, who is Black, said the district’s affinity group for staff of color had five participants when she started the job. Today, it has more than 40. “It’s all about building connections.”

In Phoenix, Jenkins said making connections is the primary goal of the district’s Black Alliance, a coalition of Black educators who support one another and advocate for Black students. Black teachers make up less than 10 percent of the teacher workforce here and it isn’t uncommon for new Black hires to express feeling uncomfortable on the job, she said.

“We have a young teacher who just started,” said Jenkins, who leads the alliance. “We had to make sure she was connected with someone on her campus who could support her and talk her off the ledge whenever she started to feel like, ‘I can’t do this.’”

“Grow-your-own” teacher programs are one answer to getting teachers in the door who represent their communities and have the local support they need to stay in the classroom when things get hard. When successful, the programs have the double benefit of building a teaching pipeline and diversifying the workforce.

The University of Nevada, Las Vegas, partners with Clark County high schools to encourage students of color to enter the teaching profession. The program has seen a 5 percent increase in Latino students in its teacher preparation program from 10 years ago. More than 30 states partner with the nonprofit Educators Rising, which supports diverse high school and college students interested in entering the teaching profession. Students who participate are four times more likely to stick with their plans to teach.

In Phoenix, there will soon be an entire new high school, scheduled to open in 2023, focused on inspiring young people to stay and teach. Phoenix Ed Prep will offer college-credit courses in teaching, social work and psychology to students interested in education careers, according to district staff. Incentives like student loan forgiveness and help buying a home and car, may also entice graduates to stay, according to the school’s principal-in-waiting, Alaina Adams.

“What we’re aiming to do is get into the beginning of the teacher training continuum, the pre-pre-service, the shadowing and mentoring, to fortify our local pipeline,” Adams said.