The doctor told the young soccer goalie that his chest x-rays were the worst he’d ever seen.

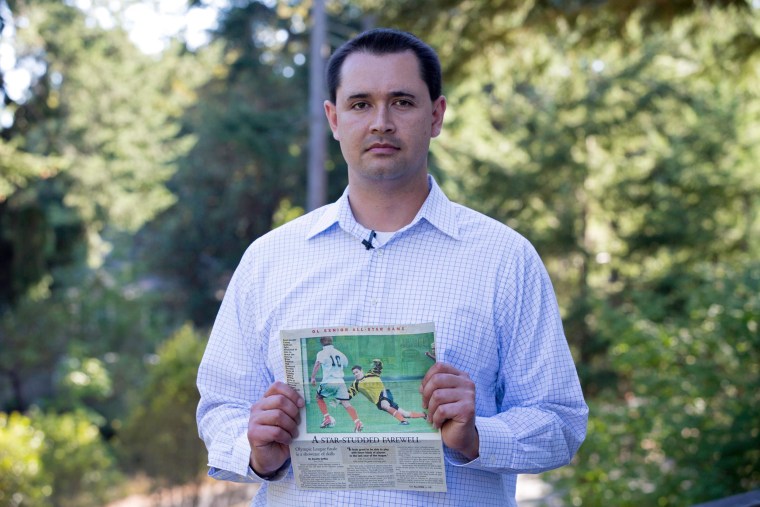

Just 21 years old, Casey Sullivan was floored by the diagnosis of stage 4 Hodgkin lymphoma. The x-rays showed he had a tumor in his chest, he says now, “the size of a soccer ball.”

A dozen years later, Sullivan is grateful that he’s still alive. Now a married father of two little girls in Gig Harbor, Washington, he’s passed on his love of the game he played from childhood through college to his kids. But he says he won’t let them play goalkeeper, and is wary of letting them play on the surface that he thinks might have helped make him sick.

Starting at age 16, Sullivan had played most of his games on crumb rubber turf, a synthetic surface made of recycled tires. As a goalie, he spent hours on drills that required him to plunge into the turf again and again, and the little black specks of rubber kicked up by each impact had gotten into his mouth, his clothes and any abrasions on his skin.

Like some other ex-soccer players, Sullivan is now wondering whether those little black granules may carry a health risk. After he saw a local TV news report about a Seattle soccer coach who had compiled a list of former players – most of them goalies – who’d played on crumb rubber turf and later contracted cancer, he says he had an “a-ha moment.”

“On my mind, my family's mind, was what caused the cancer. The doctors never had a good answer,” he said.

Artificial turf fields are now everywhere in the United States, from high schools to multi-million-dollar athletic complexes. Most of the 11,000 fields are made of crumb rubber, which became popular a dozen years ago. Called styrene butadiene rubber, or “crumb rubber,” the turf contains tiny black crumbs made from pulverized car tires, poured in between the fake grass blades. The rubber infill gave the field more bounce than previous synthetic surfaces, cushioned the impact for athletes, and helped prevent serious injuries like concussions.

Do You or Your Kids Play on Synthetic Fields? Share Your Story

Schools and local governments liked the benefits of the fields. They don’t require pesticides or herbicides to maintain, they don’t need water to live, and they can withstand heavy use year-round. They also provide a means to recycle millions of discarded tires.

But as any parent or player who has been on the fields can testify, those tiny black rubber crumbs get everywhere. In uniforms, hair, cleats and socks. For goalkeepers, whose bodies are in constant contact with the turf, the issue is multiplied.

Said Sullivan, “You’re consistently hitting the ground. Your face is essentially in the field turf, in the rubber for all intents and purposes. … Every time, you’re getting a couple pellets in your mouth.”

Critics have asked whether those little black specks are linked to any health risks. Amy Griffin, a coach at the University of Washington, compiled a list of 38 U.S. soccer players – 34 of them goalies – known to have contracted cancer. It was her tally that first got Sullivan asking questions about crumb rubber turf.

“I’ve coached for 26, 27 years,” Griffin said. “My first 15 years, I never heard anything about this. All of a sudden it seems to be a stream of kids.”

No research has linked cancer to artificial turf. Griffin collected names through personal experience with sick players, and acknowledges that her list is not a scientific data set. But it’s enough to make her ask whether crumb rubber artificial turf, a product that has been rolled out in tens of thousands of parks, playgrounds, schools and stadiums in the U.S., is safe for the athletes and kids who play on it. Others across the country are raising similar questions, arguing that the now-ubiquitous material, made out of synthetic fibers and scrap tire -- which can contain benzene, carbon black and lead, among other substances -- has not been adequately tested. Few studies have measured the risk of ingesting crumb rubber orally, for example.

NBC’s own extensive investigation, which included a review of the relevant studies and interviews with scientists and industry professionals, was unable to find any agreement over whether crumb turf had ill effects on young athletes, or even whether the product had been sufficiently tested.

The Synthetic Turf Council, an industry group, says that the evidence collected so far by scientists and state and federal agencies proves that artificial turf is safe.

“We’ve got 14 studies on our website that says we can find no negative health effects,” said Dr. Davis Lee, a Turf Council board member. While those studies aren’t “absolutely conclusive,” he added, “There’s certainly a preponderance of evidence to this point that says, in fact, it is safe.”

Crumb rubber is an “environmental success story,” said Dan Zielinski, spokesperson for the Rubber Manufacturers Association.

“There are benefits here,” Zielinski said. “The potential risk, as we know it today, is extremely low.”

Environmental advocates want the Environmental Protection Agency and the Consumer Product Safety Commission to take a closer look. While both the CPSC and the EPA performed studies over five years ago, both agencies recently backtracked on their assurances the material was safe, calling their studies “limited.” But while the EPA told NBC News in a statement that “more testing needs to be done,” the agency also said it considered artificial turf to be a “state and local decision,” and would not be commissioning further research.

“There’s a host of concerns that are being raised,” said Jeff Ruch, executive director of PEER, an environmental watchdog group. PEER has lodged complaints against both agencies. “None have risen to the level of regulatory interest.”

The EPA refused multiple requests from NBC News for an interview, and declined to expand on their statement that “more testing needs to be done.”

'Every tire is different'

One of the problems with researching the potential health hazards of crumb rubber fields is the sheer variety of materials used in the product.

Tens of thousands of different tires from different brands may be used in one field. According to the EPA, mercury, lead, benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and arsenic, among several other chemicals, heavy metals, and carcinogens, have been found in tires.

Darren Gill, vice president of marketing for FieldTurf, a prominent turf company, said that those ingredients might worry consumers, but the manufacturing process ensures that their product is safe.

“If you look at the ingredients that go into a car tire, some people take those ingredients and turn them into health concerns,” Gill said. “But after the vulcanization process, those ingredients are inert.”

Industry leaders say while they encourage additional research, studies have shown that the substances found in crumb rubber are not at levels high enough to be at risk to children or athletes.

“There are certainly chemicals in small amounts [in turf] as in many other things,” said Lee, of the Synthetic Turf Council. “You could evaluate most any material out there and you’re going to find at some level, some chemical that might cause concern.”

“The levels as they exist in tires, ground up tires, are very, very low,” he added. “The EPA has not found adverse health effect. Several state organizations have investigated it quite thoroughly.”

Existing research has attempted to measure the risk of exposure to harmful chemicals through the inhalation of gasses and particulate matter, as well as skin contact.

Studies have found that crumb rubber fields emit gases that can be inhaled. Turf fields can become very hot -- 10 to 15 degrees hotter than the ambient temperature – increasing the chances that volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and chemicals can “off-gas,” or leach into the air.

One study performed by the state of Connecticut measured the concentrations of VOCs and chemicals in the air over fields. In addition to VOCs such as benzene and methylene chloride, researchers identified various polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

The report concluded that “the use of outdoor and indoor artificial turf fields is not associated with elevated health risks,” but that more research was needed to better understand chemical exposures on outdoor fields during hot weekends and in indoor facilities, which showed higher levels of chemicals in the air.

Other studies have looked at whether run-off from crumb rubber turf is harmful to aquatic life, or whether the rate of injury on turf is lower than on natural grass.

Few studies have looked at the issues unique to goalkeepers – whether ingesting the particles by mouth or absorbing them into the body through cuts and scrapes is dangerous.

While many studies conclude that the fields studied do not present acute health risks, they often add the caveat that more research should be conducted.

• One, published in 2013 in the scientific journal Chemospheres, which analyzed rubber mulch and rubber mats, concluded that, “Uses of recycled rubber tires, especially those targeting play areas and other facilities for children, should be a matter of regulatory concern.”

• A 2006 Norwegian study evaluated inhalation, ingestion and skin exposure to crumb rubber in indoor fields. Researchers identified VOCs such as xylene, acetone and styrene, in the air above the fields. The study determined that inhalation of such compounds would not cause “acute harmful effects” to health, but that it was “not possible…to carry out a complete health risk assessment.” Researchers also concluded that oral exposure to artificial turf would not cause increased health risk.

• Another 2013 study attempted to measure ingestion, inhalation and dermal exposure risk to users, and determined that the fields presented little risk. But researchers identified lead in the turf tested, including a “large concentration” of lead and chromium in one sample. “As the turf material degrades from weathering the lead could be released, potentially exposing young children,” the report states.

According to Dr. Joel Forman, associate professor of pediatrics and preventive medicine at New York’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, in all these studies, data gaps make it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

“None of [the studies] are long term, they rarely involve very young children and they only look for concentrations of chemicals and compare it to some sort of standard for what’s considered acceptable,” said Dr. Forman. “That doesn’t really take into account subclinical effects, long-term effects, the developing brain and developing kids.”

Forman said that it is known that some of the compounds found in tires, “even in chronic lower exposures” can be associated with subtle neurodevelopmental issues in children. “Those are always suspect,” he said.

“If you never study anything,” said Dr. Forman, “you can always say, ‘Well there’s no evidence that’s a problem,’ but that’s because you haven’t looked. To look is hard.”

“I would like to see some more research,” he concluded.

'Not an Issue'

It is unlikely, however, that further research will be conducted by federal agencies.

In 2008, tests performed by New Jersey found lead on three artificial turf fields. The results spurred media coverage and concern across the country.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission, the federal agency in charge of regulating consumer products, tested turf samples. While the tests detected lead in the synthetic grass blades, the agency announced that turf was safe to play on.

That same year, an official from a regional EPA office wrote to three agency offices in D.C., including the Office of Children’s Health Protection, and recommended that the EPA undertake extensive testing, according to documents obtained by the watchdog group PEER. “My staff has reviewed the published research on the safety of tire crumb,” wrote the official, “and has found information suggesting that children’s chronic, repeated exposure to tire crumb could present health hazards. However, sufficient data to quantify toxicological risks from tire crumb exposure are not available.”

Shortly after, the EPA tested samples from two artificial turf fields and one playground. The concentrations of VOCs and other chemicals researchers found presented a “low level of concern,” the agency reported, but it declared that due to the “very limited nature” of the study and the diversity of crumb material, it was “not possible to reach any more comprehensive conclusions without the consideration of additional data.”

While the industry cites both studies as evidence that rubber crumb is safe, in response to complaints filed by PEER, both the CPSC and the EPA declared last year that their studies were limited in scope. In its press release, the CPSC wrote, “The exposure assessment did not include chemicals or other toxic metals, beyond lead.”

Since its initial tests, according to the CPSC, the agency has worked with the industry to develop voluntary standards for lead content.

The EPA refused repeated requests from NBC News for an interview. It said in a statement that the agency “does not believe that the field monitoring data collected provides evidence of an elevated health risk resulting from the use of recycled tire crumb in playgrounds or in synthetic turf athletic fields.”

“The agency believes that more testing needs to be done,” said the agency in a separate statement, “but, currently, the decision to use tire crumb remains a state and local decision.”

When NBC News first contacted the EPA in 2013, Enesta Jones, an agency spokesperson said that in 2010, after a meeting with state and federal officials, “EPA determined that this is not an issue.”

The agency does not have plans to conduct further studies, but is currently working on a “summary” of available research.

Casey Sullivan wants more research, too. But he’s already made up his mind.

“I know that goalkeepers ingest large amounts of the crumb rubber accidentally through playing on the surface. It’s unavoidable,” he said.

He would love for his daughters to embrace soccer, but he wants to limit their exposure to crumb rubber. He’s already certain he wants to steer them away from playing goalie.

“I would hope that my kids played soccer, but that they were field players and that the exposure to the crumb rubber would be less,” he said.