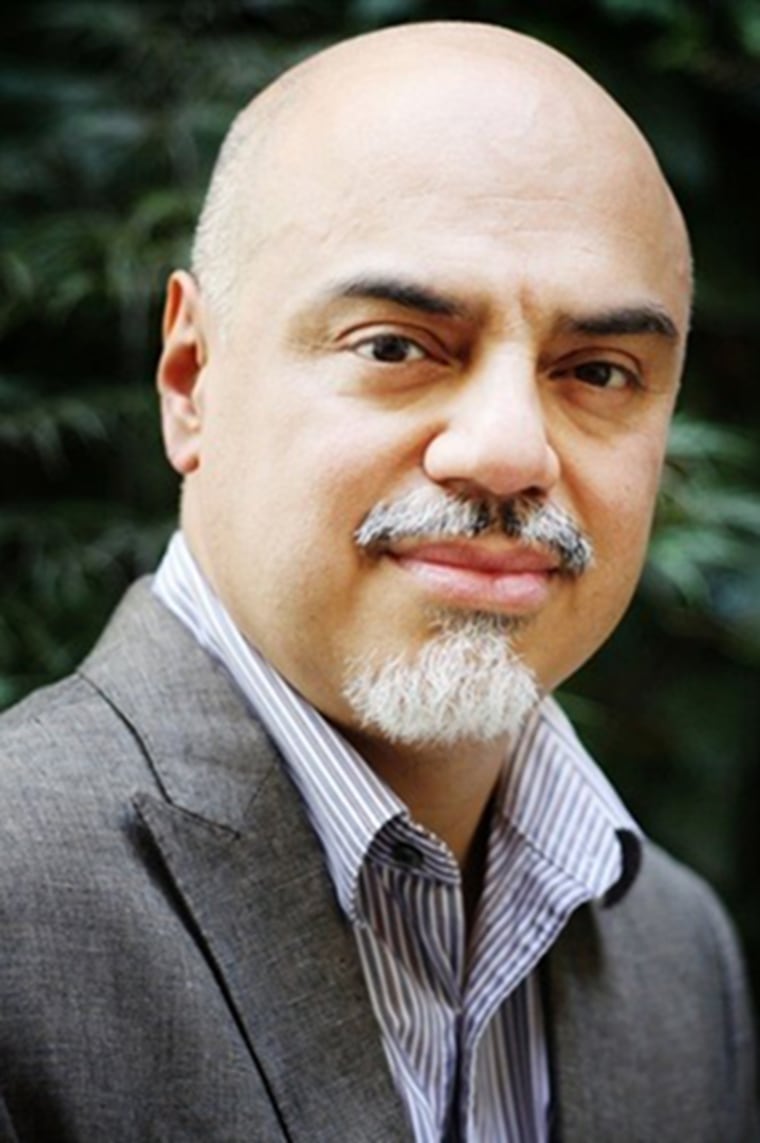

Author Héctor Tobar is not surprised by the recent spate of measures to restrict diversity and inclusion efforts in education.

“There are a lot of people who are threatened by Latinos when they are assertive and self-confident,” he said in an interview with NBC News. “And so they’re trying to keep us in our place, to belittle us. These campaigns are happening so that young Latinos don’t grow up thinking of themselves as people who matter.”

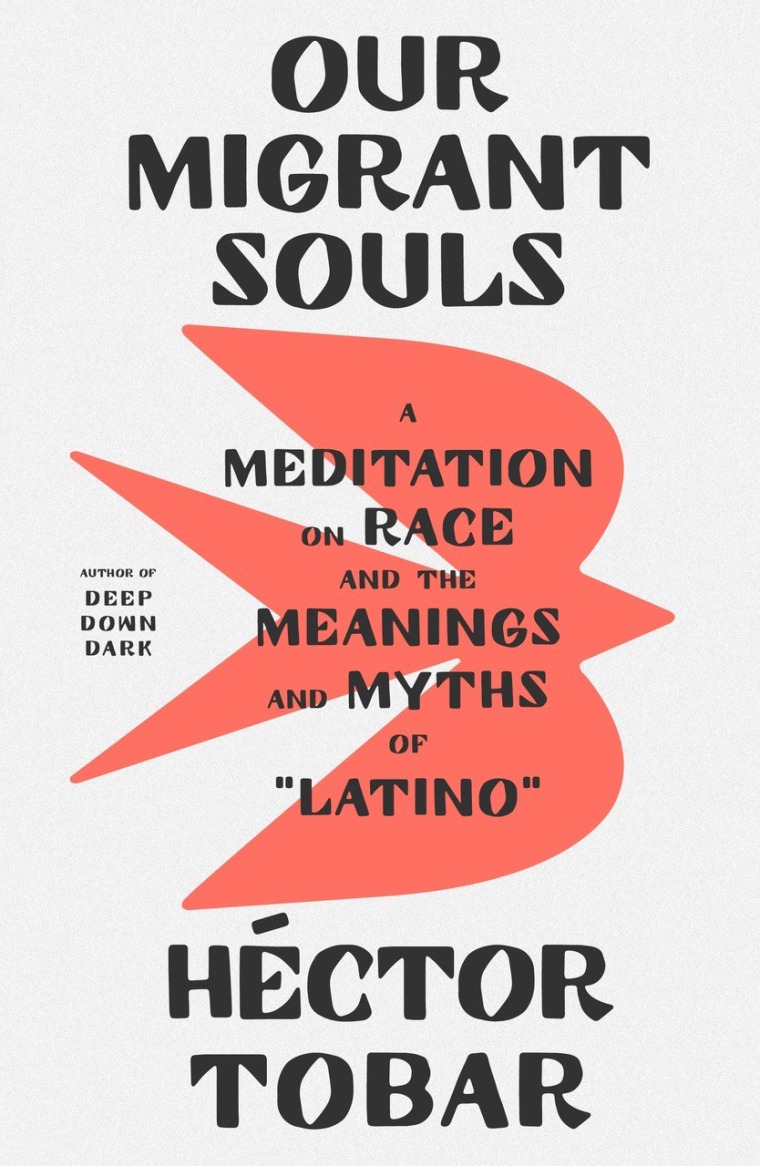

The Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and scholar rebukes such thinking with his latest book, “Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of Latino.” In it, Tobar explores what it means to be Latino in the 21st century — by reflecting on his past, visiting his parents’ homeland and taking a road trip across the United States.

He said he wrote “Our Migrant Souls” because, in his view, the national conversation about race and identity rarely includes Latinos.

“We are not seen as people who are central to the American story. We are seen as the supporting cast, like this inconsequential supporting actor," Tobar said. He points out that it is Latino labor that keeps the country functioning and that is essential to industries such as construction and agriculture — and that it was largely Latino workers who built the infrastructure of the American southwest.

As he strives to illuminate the Latino experience, he acknowledges that the construct of “Latino“ is artificial and complicated.

“Latino is the most open-ended and loosely defined of the ‘non-white’ categories in the United States,” Tobar writes. “As such it can feel like the transit lounge of American identities, one where people come and go with relative ease.”

The son of Guatemalan immigrants, Tobar, 60, was raised in East Hollywood, California. He grew up among Eastern European, Mexican and Central American families. His godfather was an African American activist, while James Earl Ray (who later assassinated civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.) lived in his neighborhood — right next door.

His family’s presence in such a setting, Tobar writes, was completely natural: “Across the United States, Latino people inhabit places that are never far from Black struggle and the history of white supremacy.”

Tobar hopes that his book will help young Latinos understand the complexities of the worlds they inhabit.

“A lot of us as Latino people grow up with the erasure of ourselves from most of the mainstream media,” he said.

Tobar said that because the press tends to focus on Latinos in crisis or as undocumented immigrants, “there is this equation of our identity with working class status, and with a lack of sophistication and intelligence."

He recalls a moment in 2010 when he was dressed casually at a suburban park and a child mistook him for an ice cream vendor.

The 'little bit ludicrous' arguments over labels

When the Pew Center asked Latinos in 2020 about their preferred pan-ethnic term, 61% of respondents said they preferred the term Hispanic, followed by 29% who preferred Latino. Only 4% chose “Latinx,” a gender-neutral alternative, which is intended to be inclusive but often sparks backlash.

In Tobar’s view, the term “Latinx” was adopted by young Latinos who wanted to show support for the LGBTQ+ community and who were somewhat distanced from the Spanish language. Many native Spanish-speakers or people raised among Spanish-speakers, in contrast, are comfortable with the ideas that all nouns have genders, with the default term for a group being masculine.

Controversy over Latinx is rooted in this generational and linguistic conflict, he explained. In addition, many Latinos heard “Latinx” emerging in the media and felt like it was being imposed on them by others.

The ongoing arguments over Latinx are “a little bit ludicrous," Tobar said. He sees both “Latino “and “Latinx” as problematic because the words bear the "Latin-" prefix.

“This is assigning a European term to a group of people who are also Indigenous and African," he said. He likens attempts to define Latinos with labels as “like using crayons, which are very crude instruments, when you need a fine-bristle paintbrush to really capture who we are.”

“Latino identity masks a great deal of cultural mixing,” Tobar said. “I like to say that Latino or even Latinx is a synonym for mixed, a person who is Latino more than likely has European and Indigenous roots, or even African roots.”

"Our Migrant Souls" has drawn wide praise; Publishers Weekly described it as “lyrical and uncompromising,” while Kirkus Reviews termed it “a powerful look at what it means to be a community that, though large, remains marginalized.”

Along his literary journey, Tobar’s book delves into everything from immigration policy to queer utopias to the cultural impact of the late iconic Mexican painter Frida Kahlo.

Tobar is the author of six books, published in 15 languages. He has been a columnist for the Los Angeles Times and a contributing writer to The New York Times. His acclaimed book, “Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine and the Miracle That Set Them Free” was adapted into the 2015 film, “The 33” starring Antonio Banderas. A professor at the University of California, Irvine, Tobar was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in April. Tobar was part of the Los Angeles Times reporting team whose coverage of the city's 1992 riots won a Pulitzer Prize.

Pushing 'our imperfect selves onto the American stage'

Looking ahead, Tobar is optimistic about the future for Latinos. “I’m very optimistic because I work with young people, and I see their energy. I see their ambition,” he said. “I see the love they have for themselves and their culture, which is wonderful.”

“Our fight is to push our imperfect selves onto the American stage. To stand as we are and force the United States to see us as we are,” he writes in his book. ”Lo bueno y lo malo (the good and the bad), the tragic and the defiant. And all the other states of being human that lie in between.”