In 1948, a California plane crash killed mostly migrant farm workers who were being sent back to Mexico. The media at the time just identified them as "deportees" and they were buried in a mass grave. The incident was immortalized by folk singer Woody Guthrie in his poem and iconic and enduring protest song, "Plane Wreck at Los Gatos (Deportee) with its haunting lines: "Who are all these friends, all scattered like dry leaves?/The radio says, "They are just deportees."

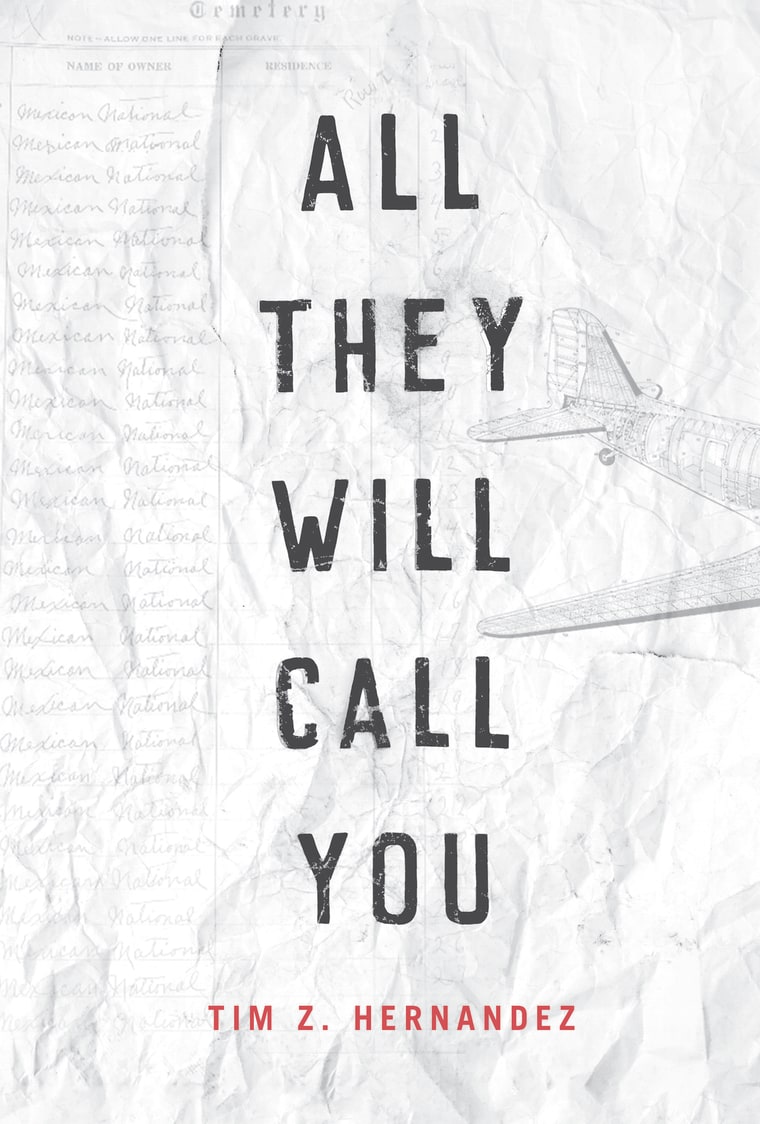

Decades later, one of the country's most exciting young writers and the son and grandson of California and Texas migrant workers decided to give a real voice to these forgotten plane crash victims. After years of research and investigation, Tim Z. Hernandez gave these "deportees" a place in history through his recently published book, "All They Will Call You."

NBC sat down with Hernandez to discuss his experience in researching and writing the book, which was published by the University of Arizona Press’s prestigious Camino del Sol Latina/o literary series.

NBC Latino: Bringing the story of the “deportees” out of the shadows has been an important journey for you. Your research managed to uncover their names and you led the charge to erect a monument with those names over the communal grave in Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno, CA.

How did these efforts become personal for you and what sort of pressures did you encounter as a writer making tough choices about what particular stories to highlight in All They Will Call You?

TZH:I begin the book with an “Author’s Note,” in which I describe to the reader my investment in this story. It begins with my own grandfather, a farm worker his entire life, who I had the opportunity to conduct a recorded interview with during his last days. Having witnessed firsthand the silences in my grandfather’s life, which were very much the silences of the campesino/ immigrant experience, I had always imagined myself being able to one day speak on his behalf.

I didn’t have the words in those early years. But it was an experience I had felt numerous times while growing up, witnessing my family navigate the obstacles and aggressions of everyday life: When my uncle was shot and killed by the police while unarmed, when my father was canned from his job of 17 years without any justifiable reason, when my mother got breast cancer and was stricken with fear—in each of these instances they were silenced, left without the proper words or recourse, they were rendered immobile almost.

And as a young man, witnessing this, you can’t help but want to speak, to burst, to explode forth with language. So I began seeking words in my early twenties. My investment in the story of the plane crash at Los Gatos Canyon, and the 28 unnamed passengers, as much as the story of Bea Franco, the Mexican Girl, (in the book Mañana Means Heaven) comes from this initial impulse, to speak on behalf of the silenced, on behalf of the dead, those who do not have the words to speak from the margins, or from the forgotten chasms of history.

NBC Latino: One of the more compelling features in the book is how expansive the cast of characters becomes. You include not only the 28 Mexican deportees and the 4 white crew members but also the eyewitnesses, the descendants of the deceased, and even the Woody Guthrie song (which gives the book its title)—so many pieces come together to create a portrait of grief at an international scale, though it can also be seen as a story about loss and recovery. What else do you hope readers will take away from learning about this particular event?

TZH: The story is expansive, and I definitely made an ambitious choice by trying to cover it all, but at the end of the day, I only included those elements that were absolutely vital to the story.

My goal was to convey, to highlight, and to elevate the human factor in this incident, from as many angles as possible. You don’t only get the perspective, or humanity, behind the Mexican passengers, because that would be such a disservice to the potential of this story.

You also get the life of the pilot and his wife, and a peek into the genealogy of the immigration officer, as much as a peek into the mechanics of the vessel that transported them all.

This story was so imbued with metaphor, symbolism, weight, that all I had to do was commit to telling as thorough a story as possible, and I felt confident the reader will make his or her own meaning of it.

The more I dug into the story, the more angles I kept discovering. There was/ is an inherent synchronicity in this story, and it had a profound impact on people inside and outside of the crash, and the more I teased all of this out, the more it became apparent just how much we are all truly inter-connected as human beings on this planet.

Just as those 32 passengers were, we too are in this ship together, all of us sharing the same fate. It’s just as Woody Guthrie wrote in his lyrics: Both sides of the river, we die just the same.

NBC Latino: You refer to the book as a “documentary novel” as opposed to “historical fiction." How and when did you arrive at this designation?

TZH: That classification was the most accurate and honest one that we (my publisher and I) felt best represented how this book was written, and how the reader should enter it. The word “documentary” brings to mind the idea of “documentation,” or “documents,” which describes the material I used for much of the book’s narrative. I used official records, accident reports, immigration documents, letters, postcards, photos, and evidence of this nature as one means of information.

The word “documentary” brings to mind the genre of “documentary film.” People in general are familiar with documentary films, especially these days. When viewing documentary films we enter with some basic guidelines, or agreements. We know that what we will be viewing is based on some “true account” of a particular actual incident.

And then—and here is the most interesting aspect of documentary films—we know that there will also be “re-enactments,” or “re-imaginings,” of specific scenarios. even if the re-enactment is a moment that no one could possibly know for sure, for instance, the first words spoken by a pilgrim when they landed at Plymouth Rock.

When given the opportunity to actually enter a three dimensional space with the characters and people of that time, to see it for ourselves with our own eyes and become a participant it, we are willing, and grateful, to suspend disbelief. This is the power of the “re-enactment,” especially when it’s substantiated by testimony and records.

While some people may refer to this aspect of my book as “fiction,” I wrote it as a “re-enactment,” or “re-imagining.”

NBC Latino: California’s agricultural heartland has been an important setting for all three of your novels, and you are part of that region’s rich Chicano literary landscape that includes such writers as Gary Soto, Juan Felipe Herrera and Manuel Muñoz. Why does the struggle of the Mexican/ Chicano working class continue to be such an important (and necessary) literary territory?

TZH: As the tides turn, in terms of demographics in this country, it is vital for us to continue to develop a growing and ever evolving understanding of who we are as a nation, and more importantly, as humanity. Without these narratives, we run the risk of what the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie refers to as “the danger of the single story.”

The perpetuation of a single story that is meant to define a group of people - whether the intention is good or bad - is never a good idea, because humanity is far more complex and nuanced than that.

The more stories we hear about an incident, a group of people, or an individual, the more well-rounded perspective we get. And this is what allows us to cultivate compassion toward one another.

This is why it’s not only important to write narratives about the “Mexican/ Chicano working class,” it’s vital to write and read narratives about all peoples, so that we continue to have a well informed and peaceful dialogue among one another.

The reason I gravitate toward these specific stories is simply because I’m an expert in what it means to be a third generation Chicano from this specific part of the world in a post-millennial America. I grew up in this specific reality. I was fed it since birth. It’s in my blood. Who better to write it? In the same way, I trust and rely on authors from other regions, backgrounds, ethnicities to tell their truth, so that I too can learn from them. In the words of the poet Quincy Troupe, “We’re all on the same team.”

NBC Latino: Your three novels trace an interesting trajectory of your growth as a chronicler and storyteller. The books become increasingly ambitious and complex, and the latest narrative covers a wider physical and emotional territory. Where do you see yourself traveling next and what lessons are you taking with you to the next project?

TZH: I do feel that this specific book was truly the one I was meant to write, and perhaps, that all the books and performances that have come before were practice, leading up to this one. Maybe I should feel this way about every book, but this one really allowed me to utilize all the tools in my box.

I’ve spent most of my adult life working in different mediums and forms, and this book reflects that. It is poetry, it is music, visual art, oral history and prose. For the time being, I’m trying hard to not think about moving quickly into the next writing project, but instead, allowing for this book to continue to work its medicine—on me, the community, and the families involved.

Also, I’ve grown more and more skeptical about getting too caught up in the factory of book-making. For me books are my ticket to get into the world, shake hands with people, share meals, and have conversations about how to better our lives, collectively and individually.

I no longer feel pulled so much by the writing itself, as I do by the direct intimate exchanges with people beyond my immediate scope of community. I’ve been thinking a lot about what this might mean for me in the near future, where it might lead me. Perhaps toward another kind of narrative medium, maybe film or back to performance.

I admire people like Harry Smith, or what Folkways did back in the early 20th century—travel the country gathering oral histories and songs from the margins of society. Or more recently, I admire the work that Quintan Ana Wikswo is doing by going into spaces of grief and gathering memory via photos and audio.

Recording what is already there is an extremely interesting prospect that I feel poses a lot of possibilities. Whatever form my work takes, it will be another step in the evolution of these tools I’ve been gathering along the way.