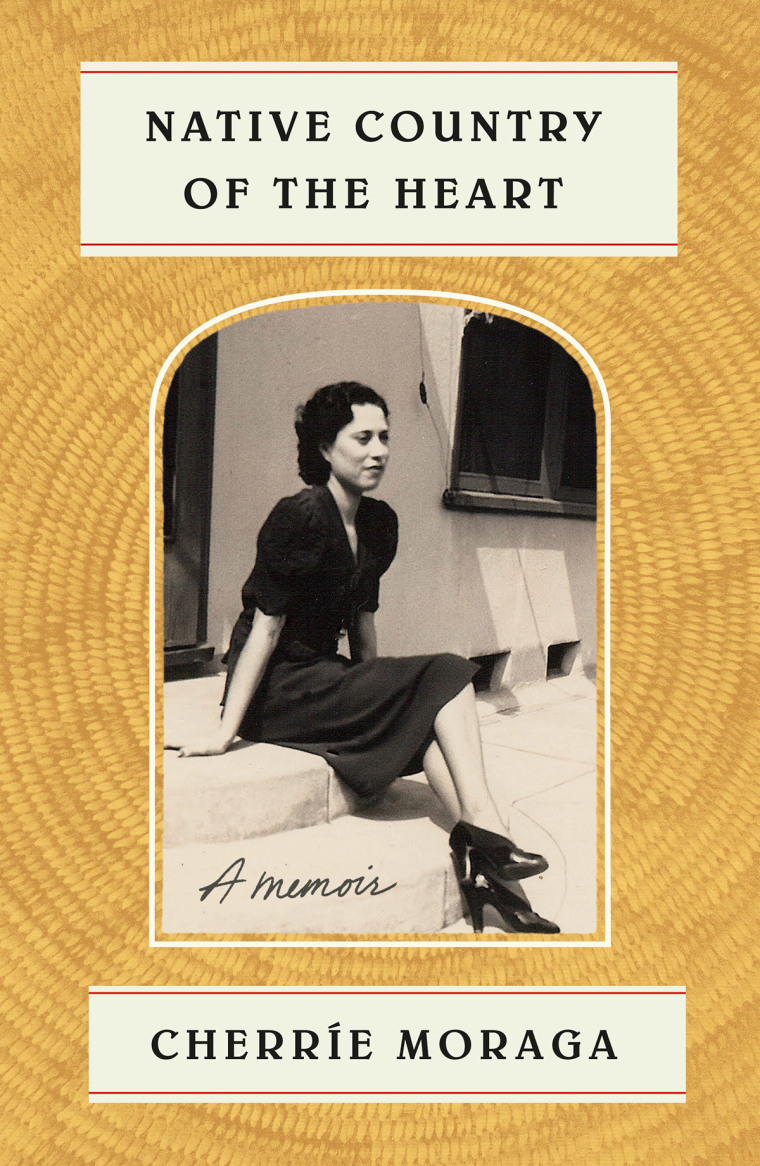

The legendary Chicana playwright, Cherríe Moraga, who’s also best known as co-editor with Gloria Anzaldúa of the foundational feminist anthology "This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color", has just released her exquisite memoir "Native Country of the Heart."

But don't expect to read about Moraga’s rise to literary stardom or even about how she and a community of notable writers conceived of the groundbreaking book that restructured feminist theory and criticism. Instead, readers of her memoir will experience a much more intimate journey: the story of Moraga’s complicated relationship with her mother, Elvira.

“I had only one romance,” Moraga writes in the preface of the memoir published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. “The love of an intractable Elvira, and this is what would shape my lesbianism and this is what would mark my road as a Mexican and this is what would require me to remember before and beyond my mother.”

The book takes the reader to Elvira’s youth in Southern California’s Imperial Valley, where her father pulled her out of school in order to labor in the fields. But her charm and resourcefulness gave her access to better opportunities, like working for the American-owned casinos and racetracks south of the border during the Prohibition era.

“I often wondered if my mother’s years in the “Salón de Oro” had ruined her — made an ordinary Mexican life in the United States impossible,” Moraga writes.

Indeed, when Elvira moved on from her glamorous place of employment to start a family with a working class white man, the roles of wife and mother became conventional duties that pushed her into periods of frustration, sometimes expressed violently.

While Moraga is beginning to come to terms with her own sexuality, she looks to her mother for strength, since her mother too appears out of sync with the gender norms of the Mexican household. Yet, Elvira enforced these norms on Moraga and her sister, JoAnne.

“I learned sexism from my mother,” Moraga explains. “She made sure I understood what the rules were and how I was to behave.”

What results is a bittersweet portrait of a woman caught between the expectations of Mexican womanhood and her own desire to strive for something different, something worthy of her intelligence and vision.

As Elvira’s physical and mental health begin to decline, Moraga’s own life is punctuated with a series of personal blessings — the birth of her son, the blossoming of a relationship with her partner Celia, and professional triumphs that included distinguished academic positions and projects that nurtured her interests in queer feminism and indigeneity.

Moraga’s education is the key to her self-actualization, while Elvira’s “inability to read and write well remained an open wound for Elvira her entire life.” Though the two women follow markedly different paths, what continues to connect them is the ache of separation from home. For Elvira, it’s Mexico; for Moraga, it’s Elvira. “There were times when I didn’t know whether my mother was truly “demented” or just Mexican in a white world,” Moraga writes.

The dynamics of the mother-daughter relationship begin to shift once Moraga finds herself having to make decisions on behalf of her mother, whose Alzheimer’s has worsened. This caretaking comes with an awareness that finally brings Moraga closer to Elvira: “I feel myself growing into the compassionate husband, the devoted eldest son, all the missing men in her life — the ones I know she will submit to, if only to be relieved once and for all of the burden of her own self control.”

Eventually, this closeness also leads to a kind of reconciliation or, at the very least, a long-desired affirmation of their familial bond.

After Elvira’s death, Moraga has to come to terms with “life without a Mexican mother,” which prompts her to write this unique memoir, a tribute that began with the writing of the eulogy for Elvira’s funeral.

“The irony of growing up and becoming a writer,” Moraga explains, “is in recognizing that our families are the truest storytellers, and that their histories are our first important stories. All of that is literature. It’s our literature.”

To that end, the story of Elvira is a story of remembering what can be easily forgotten or underappreciated with the passage of time. Moraga amplifies the need to recognize how interwoven the past is to the present, and that to understand ourselves we must locate our ancestors, who are an extension of who we are. Native Country of the Heart makes powerful statements about what is gained and lost in the pursuit of the American dream, and how the same place that affords privilege and opportunity, also demands sacrifice and surrender.

Heart-wrenching and heartwarming, Moraga’s memoir delivers new insights into the acclaimed writer’s creativity, and introduces readers to another of her significant muses: “I made a commitment to depict my mother honestly, as a woman full of complexity, contradictions, and paradoxes,” Moraga adds. “But what I wrote, I wrote out of love.”

FOLLOW NBC LATINO ON FACEBOOK, TWITTER AND INSTAGRAM.