Rehashing memories of high school bullies and fat-phobic taunts was tough for debut author Crystal Maldonado.

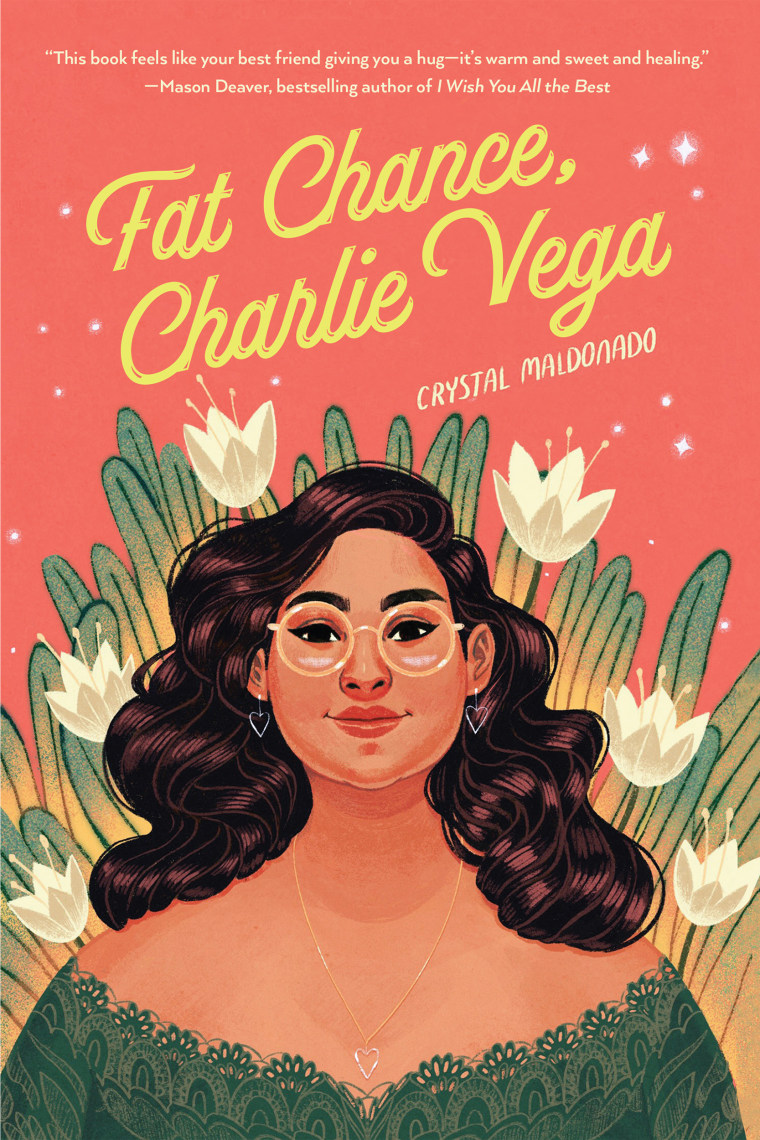

Yet dredging her pain and anxiety as a plus-size Latina girl in a small New England town was essential to portraying adolescent life in Maldonado's debut novel, "Fat Chance, Charlie Vega," which has drawn rave reviews before its release Tuesday.

"It's never 'just words.' Plus, as a writer, I have to say words are incredibly powerful, right? We can't just shrug bullying off," Maldonado said. "I wish we were kinder to victims who experienced this, because it's so hard to talk about it when you're not only hurt from whatever happened but you are also worried about how to bring up that hurt nicely."

Maldonado's title character, Charlotte "Charlie" Vega, is a thoughtful plus-size Puerto Rican teen who is still reeling a few years after the death of her father. Charlie longs to date and to be as fashionable as her beautiful, popular and very thin best friend, Amelia, but she fears that all anyone notices is her size and the fact that she is the only Latino student at their school.

Things begin to look up when the most popular boy in school asks her out to the school dance, but she is left reeling when things go very wrong. As she works to figure out how to accept herself as she is, she realizes that the pressure to be smaller and to lose weight can be overwhelming.

"I feel like girls and like women of color are just held to these impossible standards," said Maldonado, 32. "Not only are they judged through the lens of white heteronormative society, but we also have our own cultures and the different things they prioritize. The pressure is just so immense."

It's a struggle Maldonado knows well. In a recent essay on BuzzFeed, she recalled the bullying she faced as a teen, almost all of which centered on her size or her race. It was "life-changing" when she found "self-proclaimed fat bloggers" and role models, felt comfortable using the word "fat" and saw discussions about how to have a healthy body image.

Sharing her experiences felt so much more revealing and anxiety-provoking than writing a fictional story, Maldonado said.

"Writing a nonfiction piece where you're talking about your personal experience is really putting yourself out there and making yourself very vulnerable," Maldonado said. Opening up about her high school experiences felt particularly sensitive, because even most of her friends and family didn't know what she had gone through.

"I wasn't the most forthcoming as a teen. So I was definitely nervous to share this," she said. "But I also felt like I'm now at a place in my life where I'm very privileged to be able to talk about this."

As is the case with so many teen girls, the fictional Charlie's relationship with her mother is particularly fraught with tension. Formerly fat herself, Charlie's diet-obsessed mother quickly became sample-size and a peddler of diet shakes and other products, to boot.

"As my mom shed her old body and habits like a snake shedding its skin, the things that brought us together began to disappear," Charlie says in the book. "Food was no longer a celebration. We ate to survive and nothing more."

While Charlie and Maldonado both have white, non-Latina mothers and Puerto Rican fathers who moved from the island when they were young, Maldonado is quick to stress that the mother in her book is purely fictional when it comes to her obsession with dieting.

"I've had a tough relationship with my own mom, but the mom in the book is really everybody. She's everyone you know growing up," Maldonado said. "She's that friend who you go out to dinner with and says: 'Oh, are you sure you want to eat that? We could get salad.' She's all of those comments that are maybe meant to be well-meaning but are very hurtful."

It is particularly jarring when young Latina girls and women are told that the foods they grew up eating that are rooted in their heritage are somehow bad or unhealthy, Maldonado said. Because she didn't grow up bilingual and had little exposure to Puerto Rican culture outside her father's family "I didn't feel super-connected to being Puerto Rican growing up."

"But food was one way I did connect," she said. "Those were foods I loved, and they felt so warm and inviting."

Although traditional Puerto Rican foods felt like home for her and Charlie, both also had to deal with pop culture messaging that signaled that those beloved dishes were somehow more harmful than other foods.

"So many Puerto Rican foods are fried — and they are delicious! But if you are American, you're told you should never have anything that is deep fried," Maldonado said. "But what about things like my empanadas? You want me to bake those? I'm not going to bake those," she said with a laugh.

Maldonado's daughter is just a toddler, and she said she is already thinking about how to discuss body positivity and forming healthy relationships with food so she has a healthier relationship with food and her body than Maldonado did.

"I've been trying to introduce, like, empathy really early on, so that we can have these conversations and read books that talk about some of these things. I'm hoping that starting to broach these topics early — we never talked about any of these things when I was younger — will help," she said. "Weirdly, I also think her having a mom who's fat and has a body that doesn't look like everyone else's will help, too."

Maldonado said she hopes that as teens read Charlie's story, they start to realize that they can push back against diet culture and harmful messaging in their own way. A simple way is by making it a point to follow fat activists and a diverse range of body-positive accounts on social media.

"If we're mostly following celebrities, we're still just seeing a very particular kind of body. And we're getting very particular messages that can sometimes be harmful," Maldonado said. "The sooner we can start to introduce some of those other messages into our feeds and make it normal and make it something we see every day, the better."

Follow NBC Latino on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.