Of Guatemala’s 14 million inhabitants, approximately half have indigenous roots, including Maya, Garifuna and Xinca peoples. Throughout the centuries, indigenous communities have endured much turmoil, from the Spanish conquest to a 36-year civil war that resulted in more than 200,000 deaths where more than 80 percent of those were Mayan, according to a U.N.–based report.

But what's remarkable is that despite violence and death, these communities' ancient practices have prevailed.

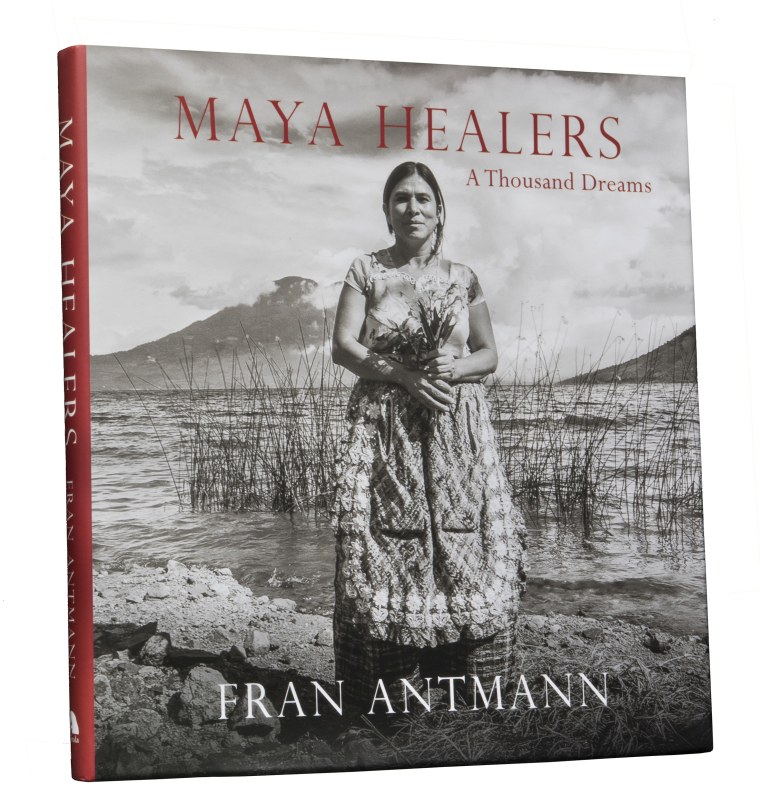

A visually stunning new book details one of the Maya's most enduring traditions, their healers.

“I was privileged to be allowed to photograph the healings, to listen to their stories and dreams, and to enter the forest with them to photograph Maya ceremonies performed at sacred sites," said award-winning photographer Fran Antmann, author of the recently published "Maya Healers: A Thousand Dreams."

Antmann, who is known internationally for her several publications and photography collections, said she chose the word "dreams" in the title not just because it’s poetic, but because it's a big part of understanding their centuries-old practices.

“The healers (curanderos) are said to derive their power and knowledge from dreams,” she said. “The healers are believed to have connections with the supernatural.”

Antmann focused her research in a village called San Pedro La Laguna on the shores of Lake Atitlán.

In rural parts of Guatemala, medical care is usually expensive and geographically inaccessible. Spanish is a distant second language to the indigenous population, and many feel disdain from doctors. This explains, Antmann said, why it is more comforting for members of some indigenous communities to go to their local healer.

Healers are determined at birth, and it is believed that individuals are born with this “don,” or gift. It’s considered a sacred profession, and one decides to accept it or not. They don’t go to medical school, nor do they get paid.

Healers who use objects to realign the bones, and then their hands to finish the treatment are called “hueseros” or “bonesetters.” They feel like they don’t even guide their hands to heal, explains Antmann, their hands guide them.

“The bonesetters often describe how they found through dreams the sacred bones they use for healing,” said Antmann. “For the Maya, the place and role of dreams is ingrained in their culture.”

Antmann was impressed by the faith of the patient and the healer.

“The healing takes place where the patient lives, or sometimes in their sacred Maya spaces,” said Antmann. “The whole family is involved – it’s a communal affair. Family members are praying in the adjacent room, and their participation is integral in the healing process.”

The Maya's rich traditions have survived much upheaval and violence since the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century.

For Antmann, who was born in the Bronx, New York to German and Austrian Holocaust survivors, it's been a privilege to be able to witness the Mayan way of life.

“I feel an umbilical cord to Guatemala,”Antmann said, adding that her adoptive daughter is from Guatemala.

As a Fulbright scholar, she spent 1979 through 1981 in the Peruvian Andes recovering the work of the late acclaimed but forgotten photographer Sebastian Rodriguez. A current professor at Baruch College in NYC, she spent the past 12 summers in Guatemala. Though she has recently focused on Guatemala, she has devoted much of her award-winning photography to documenting the people and places of Mexico and Peru.

“What is most significant to me is the way I was accepted into this community, and how I gradually gained access to and built a bridge of trust to the families and natural healers,” said Antmann.

Another important part of this long trajectory was the experience of going back to San Pedro with the book in hand, sharing it with the healers, and seeing how much it meant to them," she said. "I can't think of anything more gratifying for a photographer working in another culture.”

For more information on the book: http://www.franantmann.com/book-maya-healers