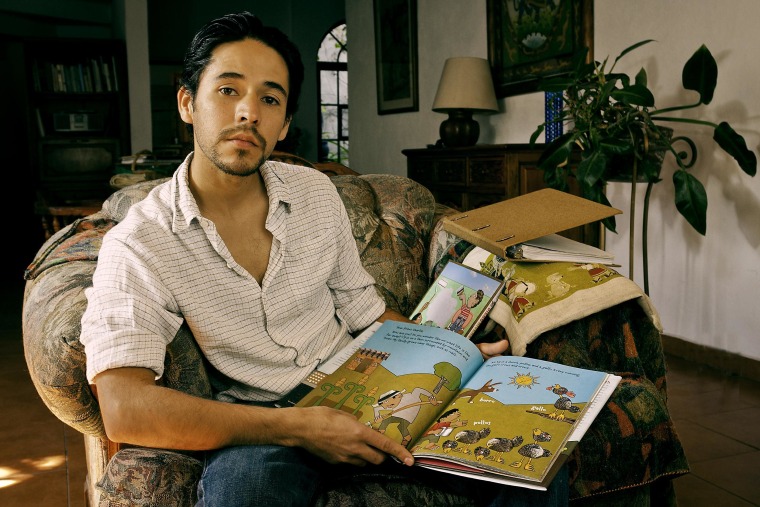

Award-winning children's book author Duncan Tonatiuh grew up with his feet firmly planted in two different worlds. Born to an American father and a Mexican mother, he was raised in a small city in central Mexico, San Miguel de Allende, but left as an older teen to finish high school and attend college in the U.S. Recognizing the freedom that comes with having two passports, Tonatiuh has used his experiences to create children's books known for their unique and beautiful illlustrations as well as for their serious subject matter - including desegregation in schools or the dangerous journeys of undocumented immigrants.

“I think kids are extremely intelligent. But I think that sometimes we don’t give them the credit they deserve,” said Toniatuh. His aim is to share with children things that he finds important and interesting, in an accessible and understandable manner. “Hopefully my books help Latino children realize that their stories and their voices are important,” he said.

Toniatuh used his experiences in Mexico and the U.S. as a basis for his first book, Dear Primo: A Letter to My Cousin, where he compared and contrasted the lives of two "primos," or cousins, one from rural Mexico and the other from urban United States. While the book presents the differences in Charlie’s and Carlitos’ lives, the heart of the story centers around how much the two boys are alike.

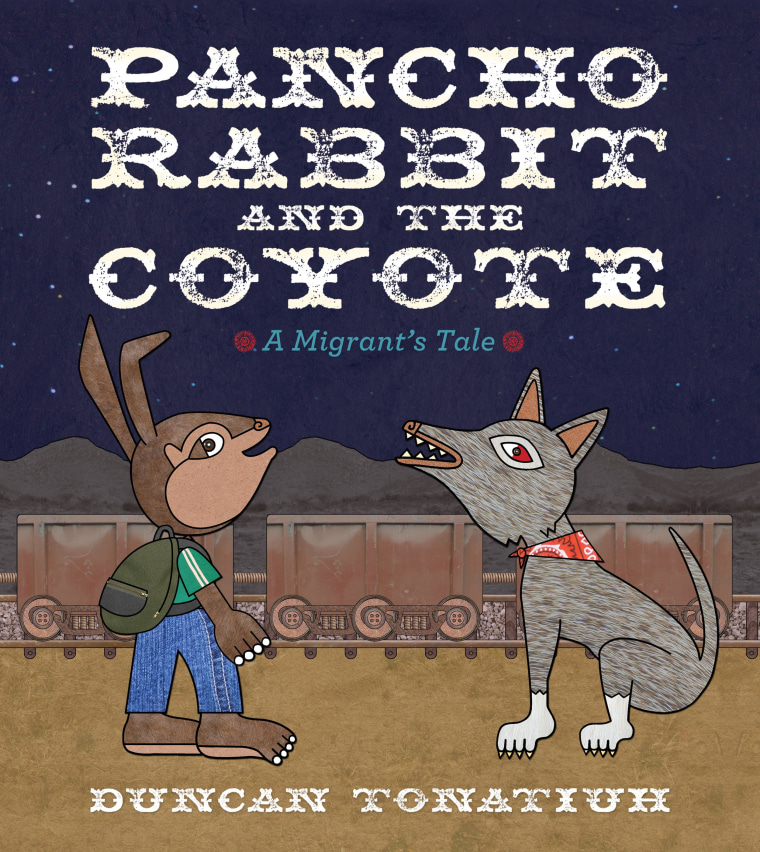

But his bicultural childhood also brought him into contact with the experiences of friends and neighbors in San Miguel who left their home seeking better opportunities in the United States. Their stories inspired his book, Pancho Rabbit and the Coyote, which he wrote to be an allegory of the dangerous journey many undocumented immigrants undergo when they come to the United States. The book won the 2014 Tomás Rivera Mexican American children's book award.

As to whether the subject matter is too heavy or political for young children, Tonatiuh said he has been very pleased with the readers' response. He was especially moved after a group of fourth graders in Austin, TX, read it, then sent him a video about their own immigrant experiences.

“I try to make books about things that I’m passionate about–social justice, history, art,” explained Tonatiuh.

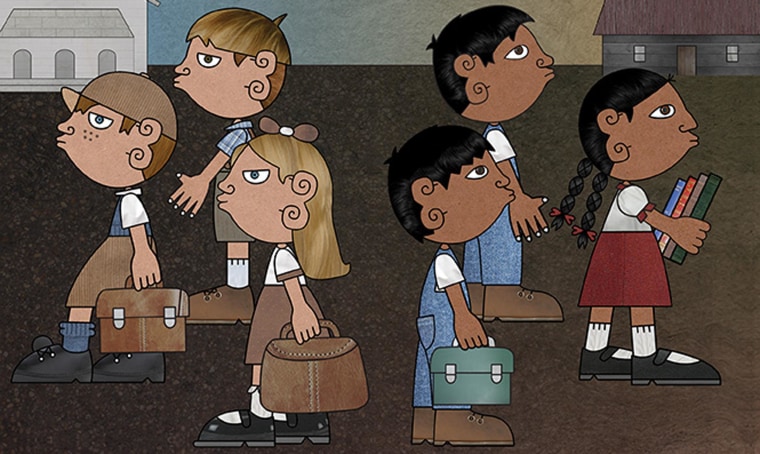

His latest children’s picture book, Separate Is Never Equal: Sylvia Mendez and Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, tells the story of the Mendez family and their daughter, Sylvia, an American citizen of Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage who spoke and wrote perfect English, but was denied enrollment to a California “whites only” school. The Mendez family fought back with a lawsuit. Nearly 10 years before Brown vs. Board of Education, the Mendez case led to the integration of California’s schools in 1947, and paved the way for the desegregation of schools across the United States.

Tonatiuh's distinctive artistic style is influenced by ancient Mexican art, in particular the ancient art and scripts known as the Mixtec codex. The Mixtec was one of the major civilizations of Mesoamerica in pre-Colombian times. Today, indigenous groups in southern parts of Mexico like Oaxaca are known as Mixtecos.

The author and illustrator's interest in Mixtec art came about in college while he was volunteering at a center in New York. He struck a friendship with an undocumented immigrant named Sergio, who was Mixteco. According to Tonatiuh, many of the Mexican immigrants working in grueling jobs in the service and construction industry are MIxteco, Toniatuh said.

“I was surprised when I met Sergio and other Mixtecos,” said the author, “because they still spoke the native dialect of their villages, even though they were in a foreign country in a huge city thousands of miles away.”

Toniatuh did some research, and was delighted when he found books with images of Mixtec codex from the 14th century. He had seen images of the codex in his elementary school textbooks or codex-like drawings at the craft’s market in San Miguel, but he had never really paid attention to them.

“When I saw those drawings that day,” Tonatiuh says, “something clicked and I decided I was going to make a modern day codex of Sergio’s story,” which he did for his senior thesis in college.

That distinctive style has carried over into all his children’s book illustrations, including his biography of one of Mexico’s most famous muralists. Tonatiuh’s picture book, Diego Rivera: His World and Ours, won the 2012 Pura Belpré Illustration Award, and it different from other children’s biographies. After introducing the artist, Tonatiuh asks the reader what he or she thinks Diego would have painted if he were alive today. Then he proceeds to compare modern images with snapshots of Diego’s work -- in Tonatiuh’s own style, of course.

“Hopefully in my books they see themselves and some of their reality reflected. I hope they see familiar objects, learn about their history and traditions, and feel proud.”