The unimaginable horrors of the Guatemalan civil war can be seen through what took place in one village. But it took decades to piece together a massacre perpetrated by the country's military that defies the imagination.

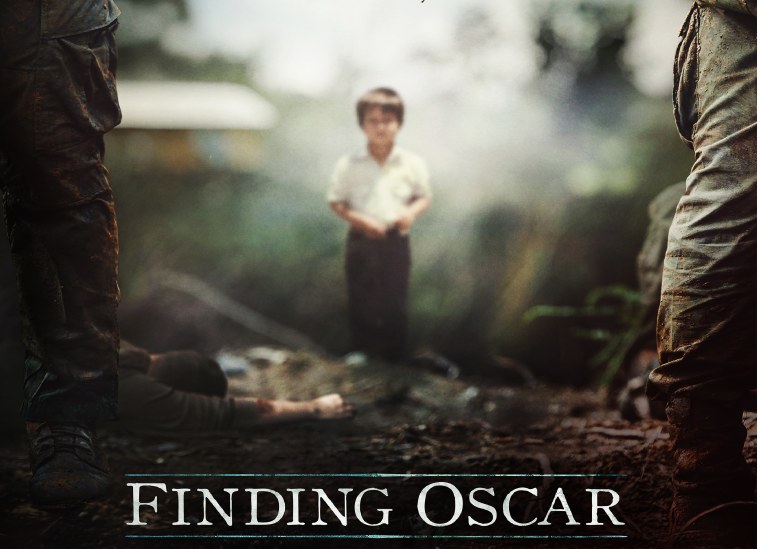

The search for answers form the heart of a new documentary, "Finding Oscar," now opening nationwide. Executive produced by Steven Spielberg, the film examines Guatemala's history - including U.S. support for the government at the time - and the war that that led to the horror of that one night, as well as the search for the children who would serve as living proof that the event occurred.

Until one fateful night, Dos Erres was a typical village in Guatemala. It was largely removed from the civil war that had gripped the country for decades. Most of its inhabitants were farmers. It was home to about 40 families, including 70 to 80 children. It contained one school, two churches, and a community well located in the center of town. Although Dos Erres – the name means “Two Rs” – was situated in a remote section of the country, one resident recalls, “La vida era buena" - life was good.

That all changed on December 6, 1982. Acting on the false belief that some villagers were sheltering weapons for local guerilla fighters, government-backed commandos stormed the town and rounded up all of the inhabitants. After a night of brutality, rapes and interrogations, the decision was made to “disappear” the entire village.

One by one, every man, woman, and child in Dos Erres was beaten with a sledgehammer and then tossed into the local well. Some young children were thrown in alive. One man, who happened to be out of the village that day, lost his wife (who was pregnant) and eight children.

Even cats and dogs in the village were killed. Then a grenade was thrown into the well, and it was covered up. With no witnesses, what happened in Dos Erres would not be known for decades.

But two small boys survived this massacre.

Their stories, and the efforts of human rights workers, forensic anthropologists, and U.S. officials to secure justice for the victims of Dos Erres are the subject of "Finding Oscar."

“It was a remarkable journey, and it was a story that needed to be told,” producer Frank Marshall told NBC Latino. “I’m a storyteller and I thought it was an incredible story.”

Marshall, a veteran filmmaker whose credits include everything from "Raiders of the Lost Ark' to "Sully," described "Finding Oscar" as “a real labor of love.”

“It is obviously a harrowing tale; you do have to deal with the horror," Marshall said. "But for me it is an intensely human story and my hope was that there could be light at end of the tunnel. This is also a story of perseverance and redemption. Oscar’s story is actually a hopeful story.”

Finding Oscar has its roots in a 2012 ProPublica series, which gained further exposure on the radio program "This American Life." It is a sprawling tale that stretches from the hamlets of Guatemala to suburban Florida to snowy neighborhoods in Boston and Winnipeg, Canada.

This documentary contains images that would not be out of place in a horror film. As scientists lay out rows of exhumed skeletons from the well in Dos Erres, there are glimpses of who they used to be. Many of the bones have the items these people wore on the last day of their lives arranged neatly beside them: children’s play clothes, a brightly-colored poncho, a farmer’s hat. One tiny skeleton rests next to a baby’s bottle.

During Guatemala’s three decades-long civil conflict, some 40,000 people were “disappeared” by government forces, leading to what one expert in the film refers to as “an entire population of the vanished.” For much of this time, the U.S. backed the repressive Guatemalan government, seeing it as a bulwark against the spread of communism. A peace accord between the Guatemalan military and the rebels was finally signed in 1996, after roughly 200,000 Guatemalan civilians had died.

“What happened in Dos Erres was only one of several hundred massacres, that we know about,” said Ana Arana, a visiting scholar at the University of Arizona and co-author of the ProPublica story. “There were serious human rights abuses going on all those years, with many attacks on indigenous people.”

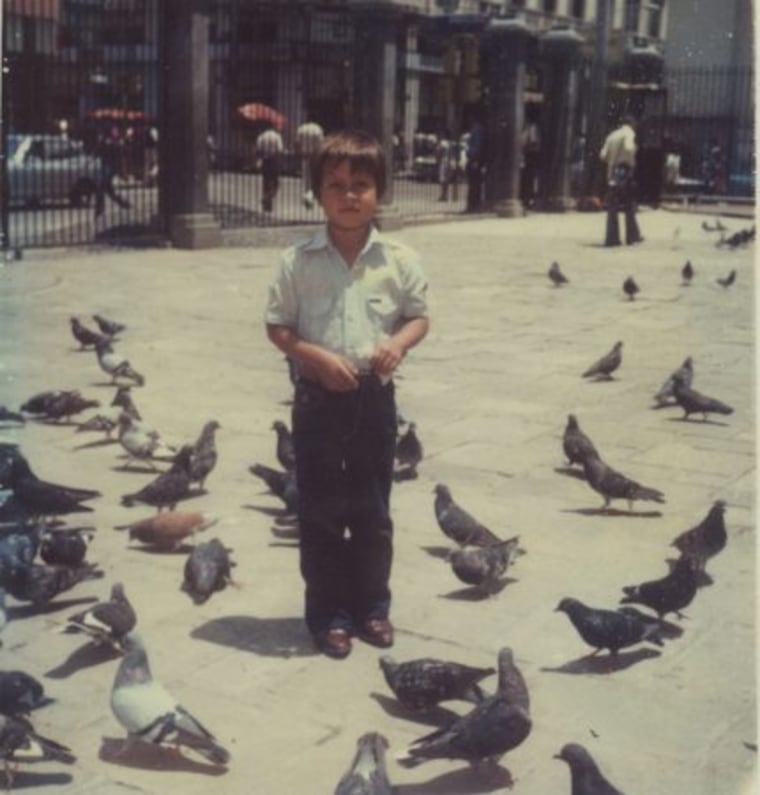

The two children who survived the massacre were spared by the commandos because they were light-skinned and had green eyes, which was unusual for the region. One was three years old, and the other was five years old. They were later raised by the families of the men who had killed their biological families.

"Finding Oscar" details how investigators painstakingly put together a case against the commandos involved in the Dos Erres massacre. Once DNA testing became available in Guatemala, it became imperative to find the surviving boys so that they could serve as evidence linking the Guatemalan government to the massacre.

This led to wrenching personal dilemmas. As a commentator in the film wonders aloud, “How do you tell someone you’re not who you think you are, and that your life up to now has been a lie?”

Ryan Suffern, the writer/director/producer of "Finding Oscar" told NBC Latino that he did not know very much about Guatemala’s history before this project.

“While I was aware of some of the Central American conflicts, and the fact that we (the U.S.) might have played a role in them, I had no idea of what was really happening,” he said. “So I tried to tell this story to a similar audience that, like me, might be unaware and unknowing.”

“What is amazing here is that Oscar’s story affords us a kind of intimacy and accessibility,” Suffern said. “You end up with a story that touches on foreign policy, immigration, and genocide in the Americas – but you do so organically by telling of the incredible search to find a little boy.”

Finding Oscar received positive notices when it premiered at the Telluride Film Festival last year. A review in the Hollywood Reporter noted that the film “is sure to achieve significant exposure wherever emotionally effective and politically-charged nonfiction work is welcome.” Another critic called it “one of the year’s must-see docs” that “should not be missed.”

Suffern spent 2½ years making "Finding Oscar" and said that it had been “incredibly rewarding” to see it resonate with different audiences at special screenings and on the film festival circuit.

Suffern recalled the difficulty in asking people to re-live some of the most traumatic experiences of their lives on camera. In addition, he interviewed several of the commandos who had participated in the Dos Erres massacre.

“I knew of their testimony and participation, so I had an idea of who they were,” he said. “But nothing prepares you for sitting down across from such a human being. Not that I would ever, ever want to rationalize their actions, but it makes you realize that there is no such thing as evil… We all probably have the potential for great good and great evil within us.”

“That made me understand how under certain circumstances, we might find ourselves doing things that we would never consider doing normally,” Suffern said.

The Dos Erres massacre was one of 629 massacres documented by a United Nations-sponsored Truth Commission. Yet as "Finding Oscar" shows, justice was a long time coming. When charges were first brought against 17 former military members in the Dos Erres case, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court threw out the case. It was not until a 2009 ruling by the Inter-American Court and the appointment of a new prosecutor in Guatemala that the case became active again.

Since then, five defendants in the Dos Erres cases have been convicted for their role in the massacre and sentenced to prison. Seven other suspects are still at large, either in Guatemala or in the U.S.; some commandos have received immunity for testifying against former colleagues. Earlier this month, a judge ordered former Guatemalan president Efrain Ríos Montt to stand trial for a second time on genocide charges.

The conflict that gripped Guatemala for so many years has had consequences in the U.S. Beginning in the 1980s, Guatemalans began fleeing the political instability and violence and resettling here; Guatemalans are now the 6th largest group of U.S. Hispanics, according to the Pew Center. There are about 1.3 million Hispanics of Guatemalan origin in the U.S., a figure that includes 928,000 immigrants.

Among these is Oscar Alfredo Ramirez Castañeda of Framingham, Massachusetts, one of the Dos Erres survivors. “I don’t know if it is fortunate or unfortunate that I don’t remember what happened back then,” he told NBC Latino.

Ramirez has given testimony against former members of the commando unit that wiped out nearly his entire family; "Finding Oscar" also features a surprise twist when he has an unexpected reunion with a lost loved one.

Ramirez describes his experience with the documentary as “really, really nice, because it helps people to know the story of Guatemala.”

Today he is married with children of his own; they know their father’s story as well. But Ramirez doesn’t think that they have fully absorbed it.

“I ask myself all the time, why did I survive this?” he said. “Some people say it was because of how we looked. No one knows, I guess. Maybe because we had to tell the world what happened in that place."

"A lot of people, most people, did not know what happened there. Now they will know, and maybe think about what happened and why it happened.”