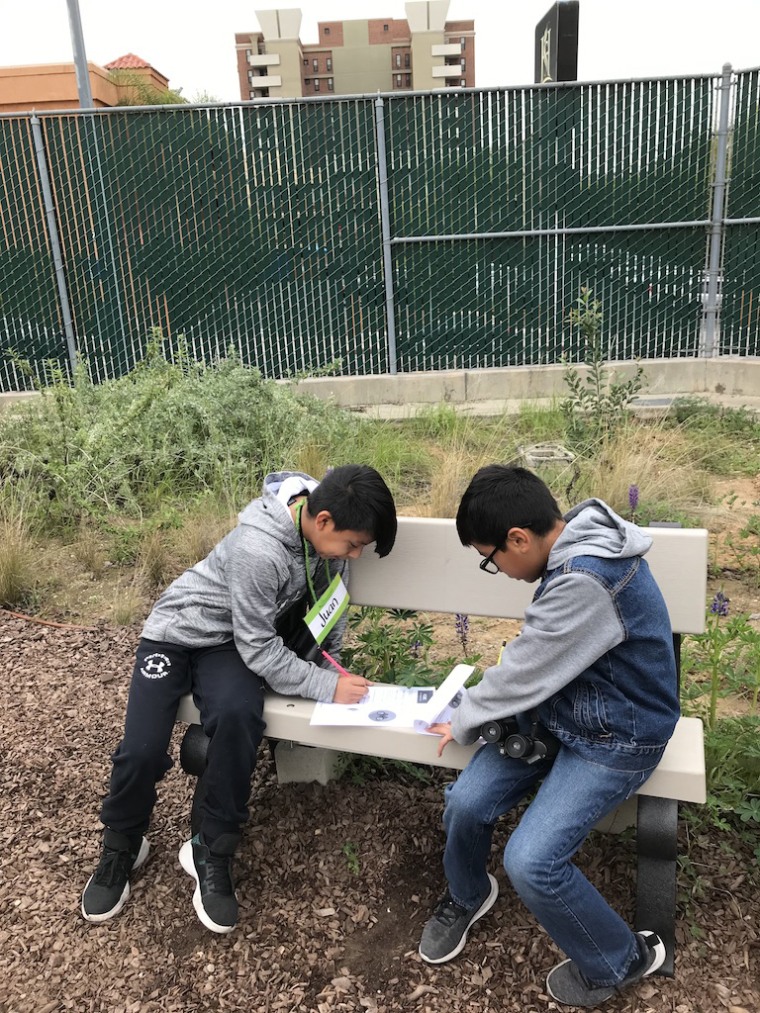

LOS ANGELES — On an overcast morning recently near downtown Los Angeles, 16 fourth-grade students scattered across their school garden to examine and identify different types of vegetation they had just reviewed in class minutes earlier.

They quickly point out California poppies, sagebrush and several other species that populate the 4,500-square-foot garden at Esperanza Elementary School. A few students crouch down to more closely observe pollinators fluttering around some of the plants.

The garden at Esperanza Elementary is one of more than 7,000 school gardens across the country, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm to School Census taken in 2015 — learning tools the federal government has encouraged since the early 1900s.

Research has shown that the gardens are tied to a number of benefits, including higher science grades and better eating habits. And at schools attended largely by low-income students and students of color, school gardens can be particularly beneficial because they can help address some of the disadvantages students at those schools tend to face, including fewer educational resources.

“We know that the learning starts in elementary school,” said Brad Rumble, the principal at Esperanza, where a majority of students are from minority communities and nearly all receive free or reduced lunch. “We don’t know where it’s going to end, but I feel like this work plants seeds within the students’ minds of what’s possible right on their own campus.”

School gardens can also offer a potential solution to the lack of racial diversity in STEM fields, according to a 2018 study in the International Journal of STEM Education, which also noted that policymakers are becoming increasingly concerned that people of color remain underrepresented in STEM fields.

According to Pew Research, blacks and Hispanics account for 9 percent and 7 percent, respectively, of STEM workers. Many believe that limited access to quality STEM education is one reason for that lack of diversity in the field.

One way to address it, authors of the study wrote, is through learning environments like school gardens.

“There is indeed a definite connection that we find in terms of how kids who would be written off often don’t have the self-esteem that they can become a scientist at some future point,” said Dilafruz Williams, co-author of the study and a professor of leadership for sustainability education at Portland State University.

But when students successfully grow a plant, learn how to compost or take certain measurements out in the field, it strengthens their sense of autonomy and science identity.

“They start thinking of themselves as: ‘Yes, I can do this. I can learn science. I am capable.’" Williams said. "That makes a major difference in terms of what happens in the future with them pursuing a path in science."

Exposure to school gardens has also been linked to improved motivation in science and math. A key reason, Williams said, is they provide students with a hands-on learning environment.

“It turns out they really like being outdoors,” she said. “They don’t like to be seated all day long in the classroom. In their interviews they talk about, ‘I just sit on my butt all day and it’s boring.’ Everything tells us they need to be moving.”

That assessment is something Lisa Lovato, principal of Dan D. Rogers Elementary School in Dallas, has seen firsthand.

According to data from The Texas Tribune, students at Dan D. Rogers — also a majority minority school — face a handful of risk factors: About 64 percent are deemed at risk of dropping out, 77.6 percent are economically disadvantaged, and about 60 percent have limited proficiency in English.

Before the school put in a garden in the 2015-16 school year, it lacked a distinction in science from the state of Texas and posted average academic performance. Since applying for the Outdoor Learning Lab Program from nonprofit Out Teach, which created the garden, the school has seen students' performance in science improve and earned a distinction in science.

Lovato credits the garden for the spike in students' performance, largely because it's a space where they can be physically active and draw real-life connections to what they're studying in class. Kindergarteners studying math have collected and sorted leaves based on size; upper elementary grades have measured the perimeter of the garden; and some teachers use the space so students can practice writing about their surroundings with descriptive vocabulary.

“If I’m a kid with ADHD and I go outside and it’s OK for me to interact with things, I don't feel like I’m not behaving,” Lovato said. “So that social, emotional aspect of the learning is really supporting our students, and they embrace those flexible learning environments.”

School gardens have also been found to benefit English language learners. A 2015 study in the Canadian Journal of Environmental Education stated that these spaces can be a source of relief for English language learners who struggle with communicating in the classroom.

Jennifer Anderson, co-author of the study and an ESL teacher at Ashland Park-Robbins School in Omaha, Nebraska, where English language learners accounted for about 37 percent of the student population in the 2017-18 school year, said that one of the more striking observations she's noted with language development is that being in the garden empowers students to ask questions.

“They’re so hesitant in the classroom to ask questions because they don’t want to feel stupid. But when they go out to the garden they’re just: ‘What’s this?’ ‘Why does this happen?’ And then I see that transferring into the classroom. I start to see those hands go up a little bit more,” she said.

Rumble, the principal at Esperanza Elementary School, noted that all the students who participated in the school's garden-learning program last year were reclassified as fluent in English.

But even though school gardens have been shown to yield multiple benefits for students, there is a lack of longitudinal studies that demonstrate their longer-term effects — including the impact they have on leading students into STEM fields — largely due to a lack of funding for this type of research, Williams said. Still, she notes that available studies indicate that these spaces create opportunities for students to be involved in meaningful learning and enables them to envision themselves as scientists in the future.

At Esperanza, one student walking back to class after spending some time in the garden said he'd someday like to create a hybrid flower, a cross between a Matilija and California poppy.

Another said she'd like to become an inventor and study birds. She and several of her classmates managed to identify 10 species that had flown around their campus that day.

“When we thoughtfully create spaces for educators to connect students to natural history on their campus, we’re fostering stewardship and a curiosity about life science and the natural world,” Rumble said. “We can ignite that interest through this work here and there’s no telling where it can lead to — doctoral studies, careers in the environment and stewardship, and just a real interest in nonfiction. It’s exciting.”

FOLLOW NBC LATINO ON FACEBOOK, TWITTER AND INSTAGRAM.